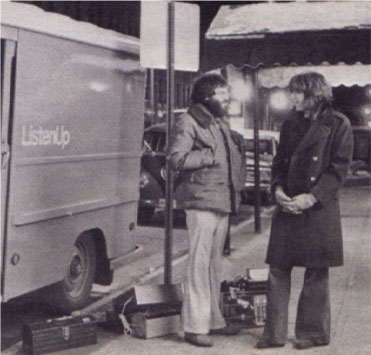

“Sound by ListenUp”

Ebbets Field’s live, intimate performances would be a minor footnote in rock history were it not for the guys at ListenUp, the local audio/video retailer and Ebbets’ sound company. Co-founder and president Walt Stinson entered into an agreement with Ebbets to do a professional mix, either simulcasting an act’s first show—going out live on the air on free-form radio stations such as KFML-FM and KBPI-FM—or recording it for rebroadcast, to promote the shows on subsequent nights. Other clubs around the rest of the country would broadcast occasional shows, but few would do it with Ebbets’ thrice-weekly frequency.

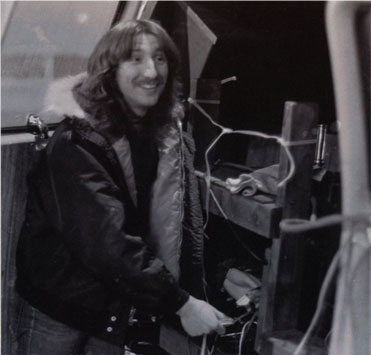

Stinson, ListenUp co-owner Steve Weiner and audio engineer Norm Simmer recorded the music straight to two-track reel-to-reel Revox tape decks at 7.5 inches-per-second with Sony mixers.

“The first shows were broadcast live—with my experience as a ham-radio operator, I had phone lines installed to feed the shows to the stations,” Stinson said. “We couldn’t do soundchecks, so we couldn’t set levels. We were right in front of the PA, so we couldn’t hear.”

“Walt had this flashlight with a big red cone on it—like a parking lot attendant, he’d swing it to shine in the stage announcer’s face to let him know we were on the air,” Simmer said. “When I started in 1974, the only master controls I had were volume and pan pots (a control for each incoming source channel)—no tone, no nothing.”

ListenUp eventually bought an old mail truck and converted it into a mobile recording studio, resulting in often uncorrupted sound quality.

“No heat—I froze my ass off in that thing,” Simmer said. “No chairs, so we moved the gear into my ’71 GMC Vandura so musicians could sit on the bench seat. I’d park illegally in front of the club. It was a window van, so people would always look in. I couldn’t do anything too illicit. I wasn’t getting paid, but it was a great way to meet chicks.”

Artists were usually glad to have the supplementary exposure. “We told them the deal—we wanted to promote their coming to Ebbets, and if we played the show on the air, it would get people to come down,” Weiner said. “All the bands approved of their broadcasts, either live or later on tape.”

At the time, reel-to-reel tape—especially live recordings—was the best way to demonstrate fine audio equipment. “Vinyl albums had limitations, and CDs weren’t out yet, so what motivated me was having first-generation audio tapes,” Stinson said. “After the shows, no matter how late at night, we’d go back to the store and listen to the tapes—‘Did we get a convincing illusion of reality?’ Steve and I paid for the equipment and tapes out of our own pockets. It was for posterity—I knew that these were great artists.”

A decade later, ListenUp archivist Phil Murray made digital backups of all the tapes recorded at Ebbets through the ’70s. “I had moved to Denver in 1974,” Murray said. “As I listened to tape after tape, it dawned on me that I was at most of those shows. The recordings are snapshots, taking you back to an amazing time and place, reflecting what it was like to be in the club on any given night. I was determined to preserve the rock history Ebbets had accumulated.”

In later years, Bob Ferbrache and Grammy-winning engineer David Glasser at Airshow Mastering added the magic of fresh digital transfers made from the original analog tapes to showcase the Ebbets Field legacy.