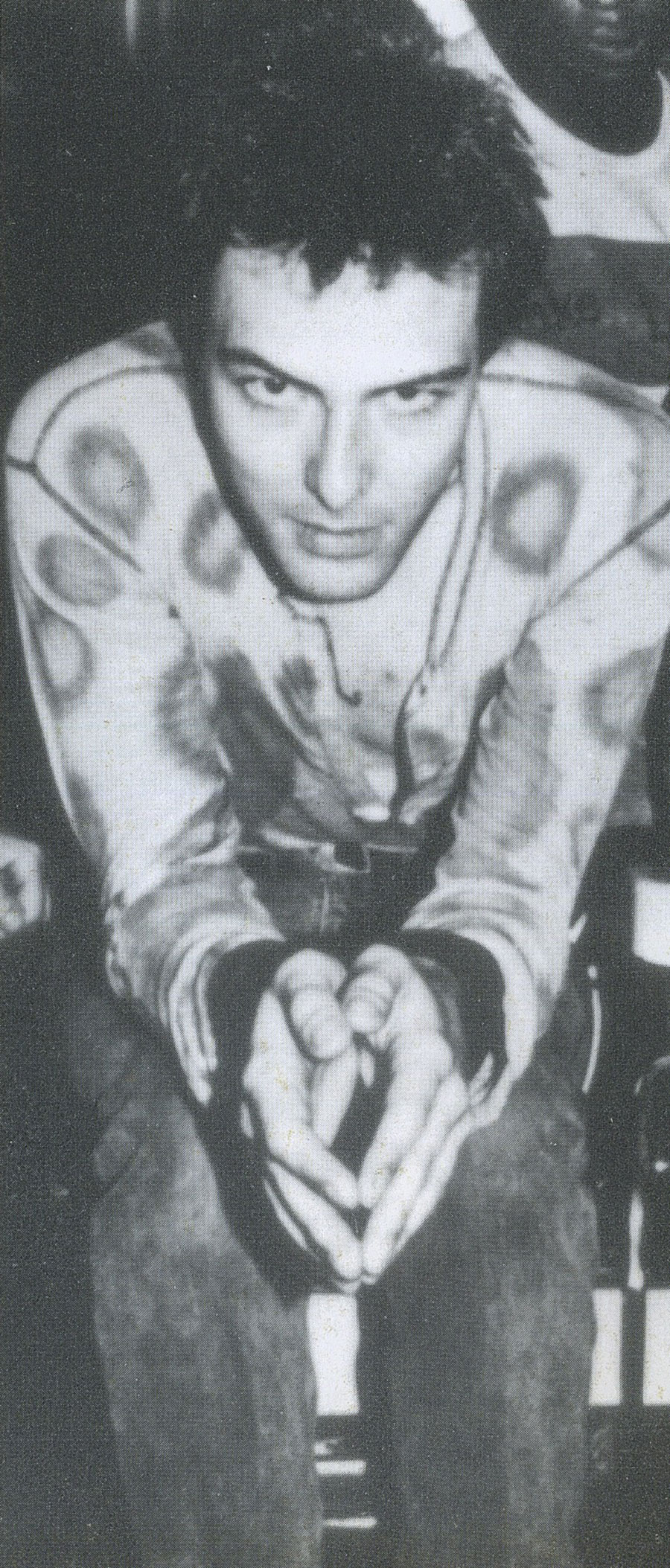

Jello Biafra

Jello Biafra, leader of the punk band Dead Kennedys and the target of one of rock ’n’ roll’s most spectacular censorship trials, was born Eric Boucher in 1958 and grew up in hippie-happy Boulder. Like a lot of disillusioned punk rockers, he left town after high school.

“In some ways it was a great place to grow up, but then it turned miserable,” he explained. “The hippies discovered Colorado and came in droves. That’s when they were considered very dangerous: ‘Don’t go down on the Hill, Eric, you might run into some hippies!’ Of course, that was where I went.

“By the time I was coming of age in junior high and high school, when I could really start to immerse myself in this culture, the culture was gone. It wasn’t the ’60s anymore, and people were just beginning to realize how stupid and boring it was to be 18 in 1975.

“The music was much more salable, respectable and slowed down. They had figured out how to take the rebellion out of everybody from Bob Dylan to Steppenwolf—yes, Steppenwolf scared people at one time—and water it down into Bad Company, Lynyrd Skynyrd and, worst of all, country rock and disco.

“Country rock ruled in Boulder. That and jazz fusion was pushed to the gills by media and record stores. Some L.A. country rock mafia had moved to Colorado and lived around Boulder, so you’d also have these pre-yuppie monied hippies swaggering into town: ‘Hi, I’m Rick Roberts of Firefall—give me a free meal!’ ‘Hi, I’m Stephen Stills—get the fuck away from that pool table!’

“But one thing saved me. Starting in the ninth grade, I got so fed up with radio that I began buying records just on the basis of which covers looked the most interesting. I discovered the used record stores. At Trade-A-Tape, I scoured the 25-cent bins and especially the free box, where they’d throw in anything they didn’t think they could sell. Looking back, this was the advantage of living in a country rock town—Stooges for a dime, MC5 for a quarter, 13th Floor Elevators, Nazz and Les Baxter for free…

“I went to see the Ramones live at Ebbets Field in Denver, and my whole life changed. They were so powerful, yet so simple—‘Yeah, I could do that, too. Why not? I think I will!’ And the rest, as they say, is sordid history. Myself, Wax Trax Records, Ministry, the Nails—we all grew out of that show.”

Boucher chose his stage name by combining the brand name for gelatin desserts and the name of the country where hundreds of thousands starved to death at the peak of Nigeria’s civil war. A self-described “cultural terrorist” and born provocateur, Jello Biafra went to San Francisco and decided to form a band. He made bad as lead singer for the Dead Kennedys, upholding an aggressive anti-capitalist style that featured smart but harsh political lyrics with furious music.

The Dead Kennedys always refused to sign with a major label—the band could have, but Biafra wouldn’t change the name (which came from his friend Radio Pete, a participant in the Colorado musical underground who would go on to become a successful publicist and consultant under his real name, Mark Bliesener).

Biafra constantly challenged the status quo. In the fall of 1979, he even ran for mayor of San Francisco on a dare. He cut his hair, circulated petitions and made the talk-show rounds, and with zero political clout he still managed to finish fourth in the race.

Then California authorities charged Biafra based on a parent’s complaint about the inclusion of artwork by Swiss surrealist H.R. Giger titled “Penis Landscape” (a poster depicting sexual organs) in the Dead Kennedys’ Frankenchrist album, released in 1985. Biafra was held on the grounds of distribution of harmful material to minors. Though he was eventually acquitted and the prolonged legal confrontation left a powerful anti-censorship legacy, the ordeal strained morale, and the Dead Kennedys broke up soon after. The obscenity trial left Biafra in debt up to his ears, without a group and unable to record for years.

But his controversial spirit raged on. He’s since harnessed his sharp observations about American politics and culture, doing spoken-word tours and releasing spoken-word albums on Alternative Tentacles, the record label he created in 1981 for the Kennedys.