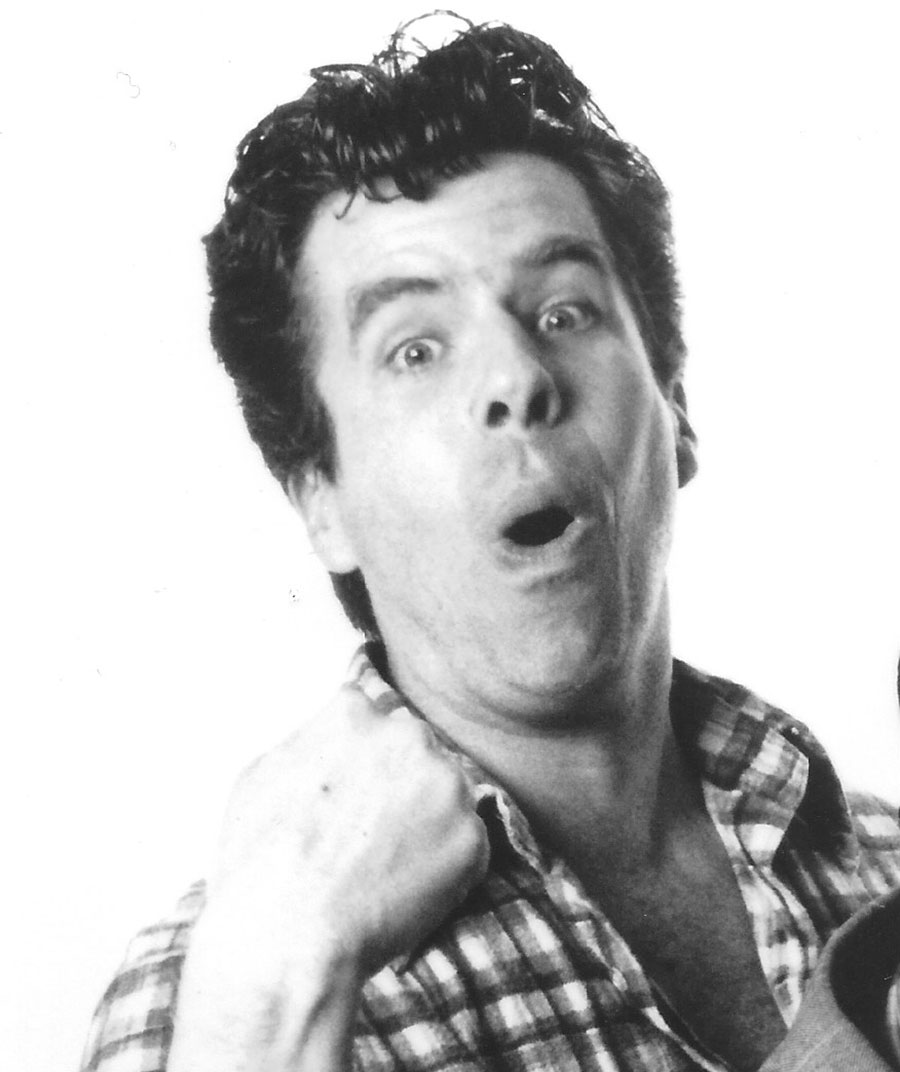

Rock eccentric Mojo Nixon—a motor-mouthed guitarist and singer-songwriter and nutcase radio personality—died on February 8, 2024, aboard a country-music cruise. He was 66.

Nixon had always been gonzo. Using his real name, Kirby McMillan, he lived in Denver circa 1980-81. “I was a young man with no plan,” he recalled when his 1988 tour brought him to Denver’s Casino Cabaret. “I was in VISTA (Volunteers in Service to America, a domestic service agency akin to the Peace Corps), and they said I could go to Colorado. I thought, ‘Hunter Thompson lives in Colorado, and Gary Hart the sex machine lives in Colorado—I guess I can go there.’

As a member of Zebra 123, he was questioned by the U.S. Secret Service for the punk band’s part in the Assassination Ball at the notorious Capitol Hill club, Malfunction Junction. “It took place November 22, 1980, which happened to be the anniversary of Kennedy being caught in the triangulation there at the grassy knoll,” he recalled. “Zebra 123 had been banned from everywhere. We weren’t skinny-tie new-wave cute, we were pissed off—three chords and a cloud of dust. We got together with two other bands and decided to put on our own show. This girlfriend of mine took a picture of Carter and Reagan—the election was going on then—and made it look as if they’d been shot from below and their heads were exploding, not unlike JFK’s. That got the Secret Service all over us. They came and gave us a big lecture, and they didn’t like our show. So there’s a file on me somewhere.

“(Then) I went to New Orleans and had the Mojo Nixon revelation. I was told to change my name and bring pop culturecide to the world.”

In 1983, the iconoclastic musician teamed with washboard player Skid Roper in San Diego to begin his assault on the American public’s sensibilities, delivering his obnoxious diatribes in a stomping roots-rock format. “It’s what I do best, a kind of spontaneous, profane thing,” he admitted.

Nixon got away with such subversive lyrics as “I saw Allah at an Arby’s” and “the Dow Jones can suck my bone.” He wrote a delicate love-letter ditty to MTV veejay Martha Quinn (“Stuffing Martha’s Muffin”) and a topical ode to the just-say-no crowd, “I Ain’t Gonna Piss in No Jar.”

Nixon’s declamations usually didn’t qualify as commercial fare, but he scored a novelty hit in 1987 with the epic “Elvis Is Everywhere,” a disrespectfully exaggerated tribute that caught on during the 10th anniversary of the King’s death. “He’s in your cheeseburgers, he’s in your mom,” he ranted to a rockabilly beat. The lyrics cited Elvis as being responsible for the Bermuda Triangle (“Elvis needs boats!”) and as being in everyone from bag ladies to Joan Rivers—although in Rivers’ case, he was trying to get out.

In 1989, Nixon performed at Denver’s Aztlan Theater and at Boulder’s Tulagi, and his Elvis watch continued. “629-239-KING” was an honest-to-goodness phone number tied to an answering machine with a plea for Elvis to phone home and for callers to leave messages about Elvis sightings.

“It was in my house, but now it’s set up where paid professionals are monitoring it,” he crowed. “It’s always busy, but a lot of people aren’t leaving messages—the weak, the puny, the pusillanimous just giggle and hang up. But one in 10 calls is a certified raving nut/lunatic/psychopath who should probably be locked up. That makes me feel good.”

Nixon’s raucous social commentary was also featured on “Debbie Gibson Is Pregnant with My Two-Headed Love Child.” “We made love 14 hours straight,” he insisted. “She’s denying that she’s incubating the incubus, but there’s even a slight chance that Debbie will be in the video.” Nixon had become a fixture on MTV, but the network decided not to air the clip.

Nixon appeared onscreen with Dennis Quaid in Great Balls of Fire, playing the drummer James Van Eaton in Jerry Lee Lewis’ band. “Jerry Lee can’t separate when he’s a nut and not a nut—shooting his wife or talking to God, it’s the same thing,” he allowed. “It’s almost like I have a career now. Before, I was in the bleachers, and now I’m in left field. But I’m still not running the basepaths like Poison—I’m in the corner taking bets from Pete Rose.”

In 1990, Nixon performed at the Gothic Theatre, singing the cruelly honest “Don Henley Must Die”—“He’s a tortured artist/Used to be in the Eagles/Now he whines like a wounded beagle.” His record company claimed it had to remove a sticker (a round picture of Henley with a line through it and containing the warning “Please Don’t Play ‘Don Henley Must Die’—It Might Upset Him”) from the album due to “legal saber-rattling from a certain powerful record industry mogul.” The label said the mogul (undoubtedly Eagles manager Irving Azoff) feared—correctly—the sticker might actually have the opposite result and encourage airplay.

“I’d love to have Don Henley come and play a few songs with me in front of 500 crazed Mojo fans,” Nixon said. “We probably agree on a lot of left-wing political issues.” Sure enough, in 1992, Henley appeared in the audience at one of Nixon’s Texas shows, climbed onto the stage and instigated a rowdy rendition of the song.

Like most in the industry, Nixon wasn’t above a bit of seasonal exploitation. At a 1992 performance at the Mercury Café, he and his band the Toadliquors performed material from an album called Horny Holidays. “You can’t find it in the big chains,” he said, “but it’s in the weird record stores—the ones run by guys with the funny haircuts, who’ve got things pierced that you didn’t know you could pierce.”

For the past two decades, the rabble-rousing musician shifted his focus to radio, joining a show on SiriusXM satellite radio’s Outlaw Country channel in 2005, “The Loon in the Afternoon.” He suffered cardiac arrest after performing a show on the Outlaw Country Cruise, an annual music event where he served as a co-host and regular performer.