Joe Ely, the highly regarded pioneer of the ’70s Texas progressive country sound, died December 15, 2025, at age 78.

Raised in Lubbock, Texas (just like Buddy Holly), Ely began playing in rock ’n’ roll bands at the age of 14. Looking to broaden his horizons, he hitchhiked and freight-hopped all over America, guitar slung across his back. “I made the mistake of picking up a bunch of books by Jack Kerouac and decided I was going to be a roving songwriter,” he said. Ely soon found himself back in Texas with a suitcase full of songs via a job with the Ringling Bros. circus as the custodian of two llamas and the world’s smallest horse, “a mean little bastard about knee-high—every day, I had fresh bites on my knees.”

Around 1972, he and follow Lubbock singer/songwriter/guitarists Jimmie Dale Gilmore and Butch Hancock formed the Flatlanders, managing to record one album’s worth of all-acoustic material in Nashville. Released in limited numbers—mostly on 8-track tapes—the band’s novel amalgam of country, folk, blues and rock styles quickly disappeared, shunned by the Nashville establishment.

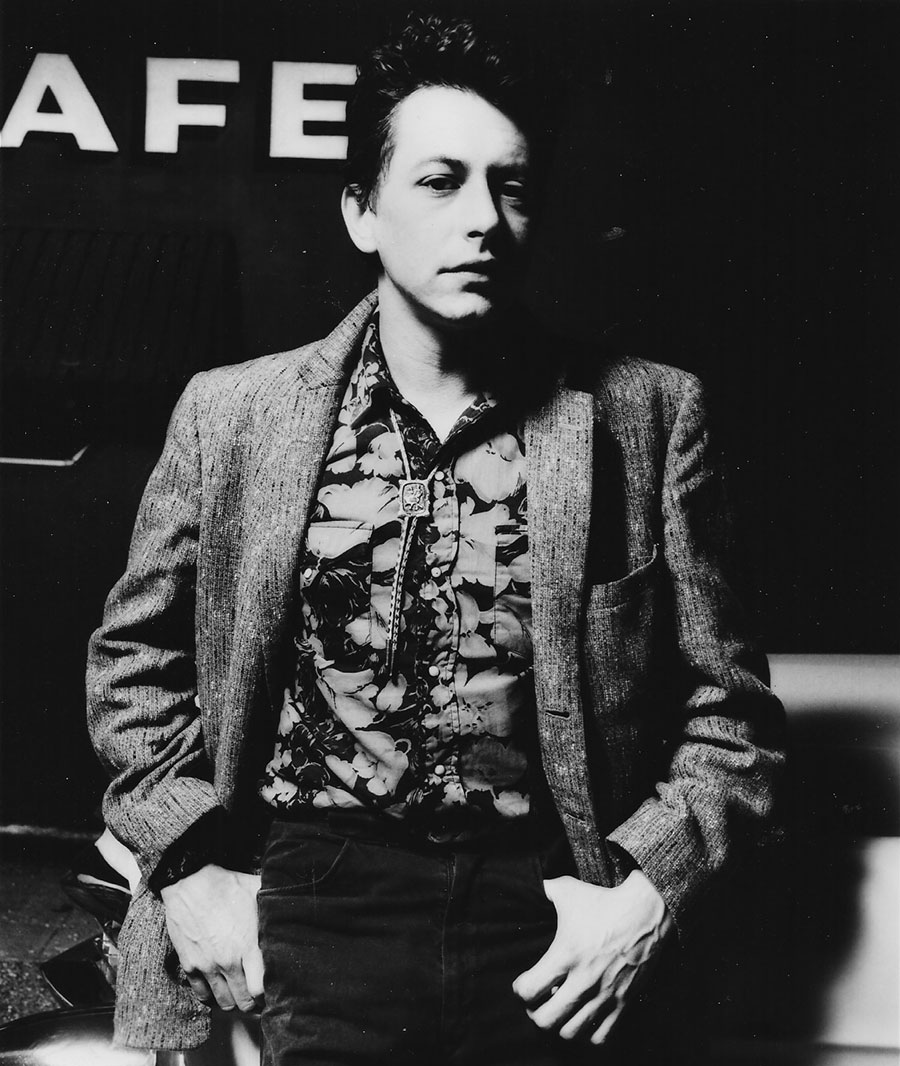

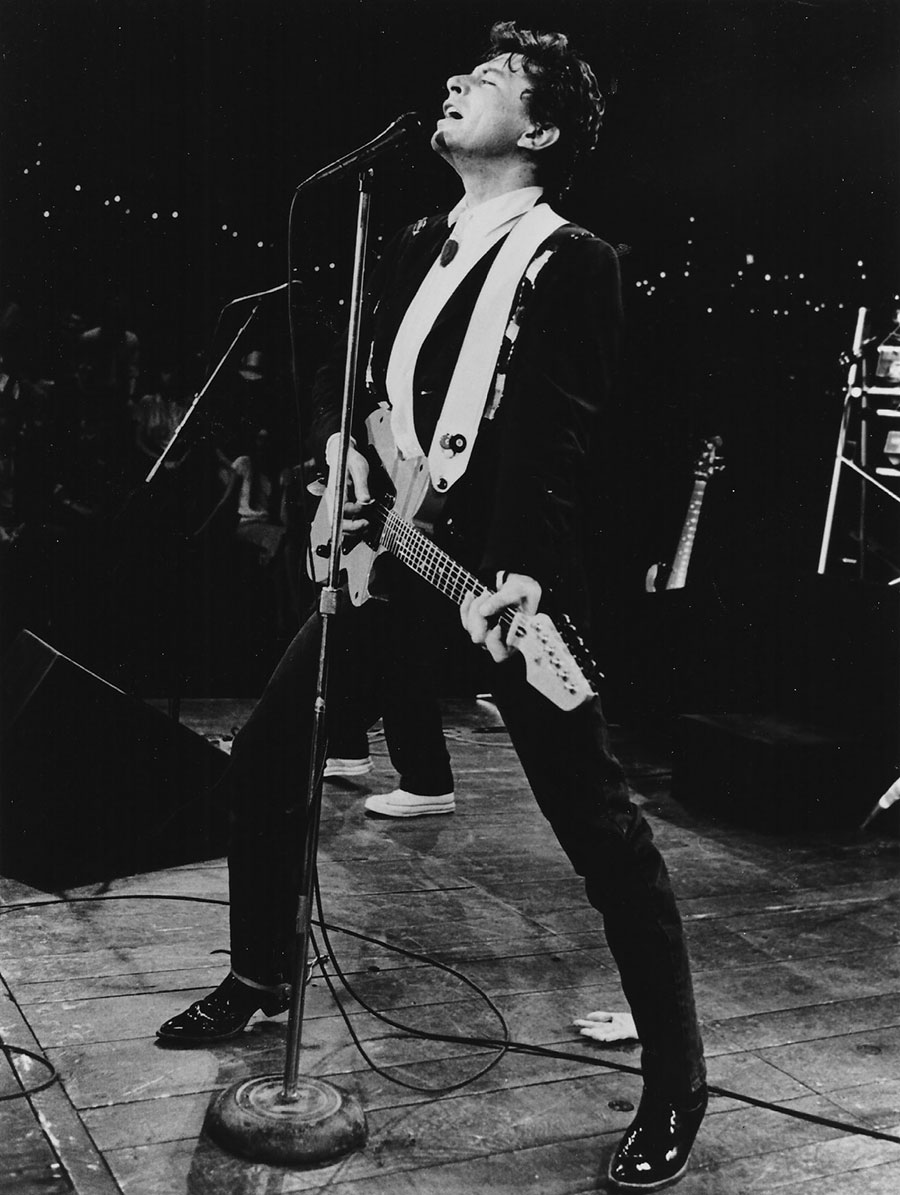

Attaching to the live music scene in Austin, Ely released his self-titled debut album in 1977. He packed honky-tonks, juke joints and concert halls from coast to coast, while his music began evolving away from country to a more rock-oriented sound. Onstage, Ely became a manic firebrand with a contagious ear-to-ear grin, offering ferocious energy and borderland romanticism.

His status as an opening act provided him with a lot of variety. He appeared on the same bill with mainstream performers ranging from Linda Ronstadt to Merle Haggard to the Rolling Stones; he shared the stage with the Charlie Daniels Band at Denver’s McNichols Sports Arena in 1981. In England, the countrified Ely became an overnight cult phenomenon, palling around and touring with the members of the Clash during the band’s punk heyday. “They look at everything upside down over there,” he said. “They love music like rockabilly and Carl Perkins, and they just latched onto me as someone who was maintaining some sort of tradition.”

America was on the verge of discovering Ely in a big way. Souping up his songs for his fifth album, 1981’s Musta Notta Gotta Lotta, he expanded his rock and country fusion into a larger scope that reflected his hard-living attitude. “The last few years on the road came together on the record,” he said. “I think it’s reflected in the titles—‘I Keep Gettin’ Paid the Same,’ ‘Musta Notta Gotta Lotta’—it’s all reflective of a working man’s rocking attitude.”

Ely hoped the edge of his newer material and his outstanding band would translate his appeal to a more contemporary level. “Yeah, it’s funny looking out on the dance floor when I play sometimes,” he said at his Austin headquarters. “Either it’s hardcore country or some fella with his hair dyed green and yellow. It makes things interesting, that’s for sure. But I try not to make distinctions. If people like what they hear—critics or kids on the street, English punks or cowboys—then that’s all that matters. ’Cause that’s all I’m gonna be doing anyway—makin’ people jump.”

But Ely never received his commercial breakthrough, despite the series of excellent albums and drawing a sizable, loyal following. His genre-bending music was perceived as too rock to be country (that is, the grab-and-release dynamics of his songs) and vice versa (at various times his bands had included steel guitar and accordion), which bewildered record labels and radio programmers. Was he new-wave country? Punkabilly? Crazed Cowboy?

On Hi-Res, his 1984 release, Ely attempted to integrate synthesizers and drum machines into his sound. While the album had its bracing moments—“Cool Rockin’ Loretta” stood as one of his finest guitar raveups—it failed to attract a new audience and only confused his old fans. “It was a departure for me, but I needed a departure at the time I was writing it,” he said. “I had a few things happen. The drummer died, the band had kinda broken up, so I had to look into other things. I wrote that album as a screenplay first, to be an all-video album—I wrote visual things and then wrote music to it. But the video part never came out.”

By 1987, the Steve Earles and Fabulous Thunderbirds of the world were getting more exposure than Ely ever did with similar brands of roots-rock. But Ely wasn’t the type to be bitter—he stuck with what he did best. “That’s guitar, bass and drums, a pretty straight-ahead kind of country rock ’n’ roll,” he said after a late night in his home studio.

Ely kept working, albeit with a lower profile, “doing behind-the-scenes stuff.” He produced a debut album for Will & the Kill, a band led by Will Sexton, Austin’s latest guitar hero and younger brother of former darling Charlie Sexton. He also put two efforts for a new record label in the can and performed solo gigs on a coast-to-coast tour, including a date at Arnie’s Broadway in Denver. “When I was writing the last album, I just decided to go hit the road, me and my guitar. I hadn’t done that in quite a few years, and it used to be all I ever knew when I first started performing. It’s pretty scary after you’ve gotten used to a band, but I wanted to play songs for people without all the arrangements, the beat. It makes every verse and guitar riff stand out—there’s nothing to hide behind. Once I did it, I realized that was a part of me I’d been missing all along.”

With each passing year, Ely’s natural lyricism and ear for rock hooks helped push a new type of progressive country to the forefront of the Texas scene. He collaborated with Bruce Springsteen, Uncle Tupelo, the Chieftains and many others.

In 2002, almost 30 years after their lone album, the Flatlanders delighted Americana fans with a series of performances. It was a supergroup reunion—or was it? The band had never really broken up, because it scarcely was a band to begin with. Hooking up in their early twenties in Lubbock, roommates Ely, Hancock and Gilmore wrote and played music together for friends, going public only when they got desperate. “We played more porches than stages, but it was about all we did—we never made a penny, but we had a lot of fun,” Ely said.

At the time of its release, the Flatlanders album showed none of the lyrical artifice or lamentable overproduction of country music. The recordings featured dobro, fiddle, mandolin and even musical saw, but the guys never thought of themselves as a country band. “It’s the fact that we came of age in the ’60s, when every kind of music was crashing into the other,” Ely said. “We always thought if that Flatlanders record had been recorded or promoted in San Francisco or New York instead of Nashville, it would have found an audience.”

It took decades, but the recording—a harbinger of the alt-country movement—finally found its niche. As the three musicians’ individual status as critics’ darlings grew, so did the legend of the time when they were together. Reissued in 1990, the original Flatlanders recording became a cult classic, as the record label appropriately named the disc More a Legend Than a Band. The Texas troubadours wrote and recorded new material as a team, in Ely’s home studio, and released Now Again in 2002. An infectious air of merriment emanated from the songs and a lengthy tour. “We’re trying to keep it so it doesn’t turn into work,” Ely said prior to a concert at the Boulder Theater. “When this is over, we’ll go back and do things we normally do.”

Tireless journeying had earned Ely the nickname Lord of the Highway. “It’s what keeps me going,” he said years earlier. “If I was always aware of myself onstage playing to a crowd, I’d never, never go on. I’m fairly self-conscious as it is, and I’d just disappear. I think it’s mostly schizophrenia!”