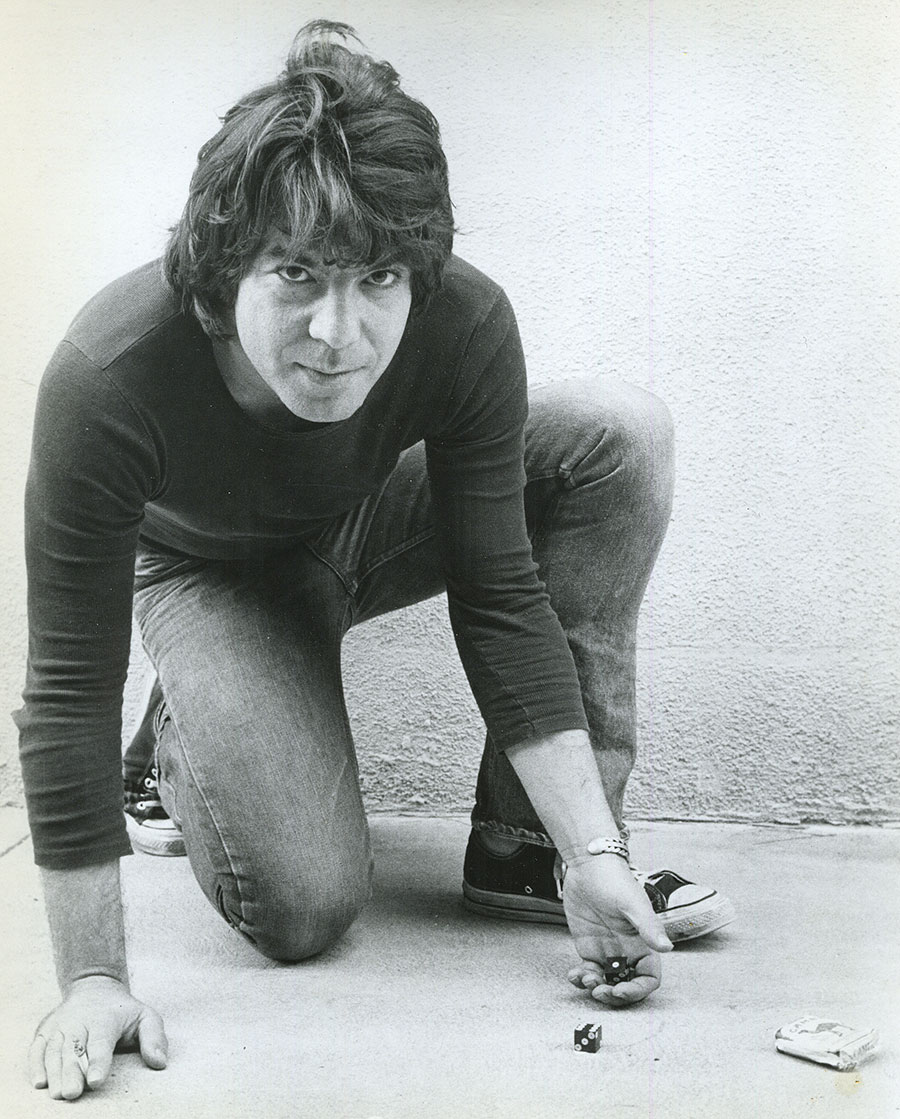

For his offbeat blend of Americana, Chuck E. Weiss was regarded as one of the coolest cats on the Los Angeles creative scene. What he described as “twisted jungle music”—inspirations that ranged from New Orleans dirge jazz to demented electric country-blues, brazenly mixed with boozy attitude and jive poetry—bristled with both cultural and historical value.

The synthesis represented the breadth of experience he gained growing up in northeast Denver in the 1950s and 1960s, where his aura (his idea of awesome was gold pointed-toe shoes and black cut-off t-shirts) gave him a reputation for being a little offbeat—but right on the beat.

“I was the only Jew for a hundred miles. I felt like a Ubangi dropped in Times Square on New Year’s Eve,” Weiss recalled with a laugh.

“Denver was more cosmopolitan then. When our parents were kids, it was a hub for the railroads. Hence you had that huge skid row downtown that’s now been yuppified as LoDo. The con was born there. All the grifters came in the early part of the century and they’d get their training and then they’d go to Chicago and other cities. That gave rise to all the bohemians coming to Denver.

“When (Jack) Kerouac discovered the place, it was already wide open. As a kid, I caught the tail end of that. People were different. The place had a lot of soul. There was a jazz station. There were so many little coffeehouses and clubs down in the Capitol Hill area—the Sign of the Tarot, the Exodus.

“We used to take the bus down to Larimer Street to go find stuff in pawnshops. You could hear a million great Mexican rock ‘n’ roll bands. There was one I liked called Mando & the Chili Peppers. Of course, they never went national, but there were always little things like that happening.

“I don’t think anyone was ever there to document it. I don’t think anybody ever took it seriously. Naturally, it molded me, so I took it seriously.”

Weiss learned to drum, and circa 1970, Chuck Morris, a local manager and promoter, asked him to sit in during an appearance by Lightnin’ Hopkins at Tulagi, a Boulder nightclub. The gig went well, and Weiss persuaded Hopkins, one of the last great exponents of Texas blues, to take him on tour.

Weiss hit it off with singer-songwriter Tom Waits at Ebbets Field, the now-defunct Denver club where Waits was performing.

“We were both sitting at the counter of the little coffee shop next door to Ebbets. I was wearing a chinchilla coat and three-inch platforms and I thought he was just some bum folk singer. I remember bragging to him about all the people I knew.”

The pair cultivated a friendship that has lasted since. Weiss subsequently moved to California, and in the late 1970s he joined Waits and an up-and-coming female artist named Rickie Lee Jones at the vanguard of an “alternative singer-songwriter” trend based out of West Hollywood’s famed Tropicana Motel.

Jones later immortalized Weiss in her Top 5 hit “Chuck E.’s in Love” and won the 1979 Best New Artist Grammy. Waits sprinkled Weiss’ likeness around a lot of his music.

Perhaps that encouraged the perception of Weiss as some sort of hipster novelty artist, but his music retained a life-learned authenticity. He played with his band at the Central, a Los Angeles nightclub, and later partnered with friend Johnny Depp to convert the space into the trendy Viper Room. He released several adventurous and risk-taking albums, including 2006’s gratefully titled 23rd & Stout.

“I always wanted to sing like a black man and do business like a Jew. Instead, I sing like a Jew and do business like a black man,” Weiss said.

In later life, L.A.’s club-crawling night owl settled down.

“The only bohemian thing that happens now is the music, when I’m rehearsing and gigging with hepcat musicians. Other than that, I lead a pretty normal middle-class life. I got a routine. I go to the barbershop, I got my cats at home, I watch sports on TV…”

After a long illness, Weiss died on July 19, 2021, at the age of 76.