As a member of such seminal bands as the Byrds and Crosby, Stills & Nash (and occasionally Young), David Crosby was assured a place in rock history. But his legacy was overshadowed by a public decline that began in the mid-’70s, when the arrests piled up—cocaine, heroin, guns, assault and battery. He was music’s most tragic figure, lucky to be alive and seemingly destined to become another rock ’n’ roll casualty.

His career reached a nadir in 1985 when he was sentenced to a five-year term at the Huntsville State Penitentiary in Texas stemming from drug and possession charges.

But Crosby beat his addiction—he finally went cold turkey, serving nine months of hard time before being paroled from prison on August 8, 1986. Arriving in Colorado for solo acoustic performances in Aspen and Denver, the 45-year-old musician spoke of his transgressions in his first face-to-face interview since his release.

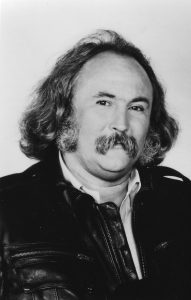

Crosby’s face was lined, and he still carried some extra pounds. But his eyes were clear and inquisitive, and, as he sat in Stapleton International Airport, awaiting his flight to Aspen, he spoke with humor and confidence.

“I am incredibly lucky to be alive,” he said with a smile and a shake of his head. “Everybody—even my closest friends—expected me to do a ‘Belushi.’”

A previous solo appearance in Colorado in 1983 provided a sobering glimpse of his lifestyle. The man nicknamed “The Lion” by friends and fans appeared at Denver and Boulder gigs wearing a down parka in 80-degree temperatures. He walked stiffly, and the open sores on his puffy face were covered with makeup. His road manager explained with surprising candor, “He just stays on the tour bus with his (freebase cocaine) pipe except when it’s showtime.”

When the bus arrived in Vail for the next day’s show, the entourage discovered Crosby wasn’t aboard—he was still in Denver, found asleep under his bed by a Holiday Inn manager. The police were called and, as Crosby was quickly escorted out by a concert promoter’s employee, he reportedly broke down crying and passed out.

It was not an isolated episode. Spin, Rolling Stone and People magazines as much as printed his obituary. Finally, Crosby surrendered to authorities.

“I was going to leave the country,” he said. “I was so scared of going to jail, I went to Florida with every intention of sailing off in my boat. But at the last minute I realized there’d be no more music, no more group, no more anything. And so I stayed.”

The stint behind bars forced him to clean up. “I played in the prison band, but I also pushed a mop and worked in the prison mattress factory,” he said. “If you ever stay at a place where they use state-made goods and you find yourself sleeping on a real bad mattress, I may be the guilty party.

“But the point is, for two or three years before I went in the can, I didn’t write a song. And that’s what scared me to death in prison. Not the guys saying, ‘Hey, rock star, c’mere—where’s all yer money?’ It was the fact that God put me on earth to write songs, and I’d gotten to the point where I couldn’t do it anymore.

“But after six months, I woke up one day and it came to me. And now I know the reality of it all—it’s not hip to be fucked up anymore, not if you want to do creative work.”

Crosby was then certifiably clean—he underwent drug testing three times a week under the terms of his parole and attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. He claimed to be re-entering public life with no anger or remorse, “just joy and a great deal of gratitude.” He had attended his 11-year-old daughter’s school pageant before his arrival in Colorado, and he brimmed with pride about the experience. “I didn’t get a chance to do that before,” he said grimly. “I was so preoccupied with drugs, I never was much of a father.”

His tour wound up with a 70-minute performance on guitar and piano at Denver’s Mardi Gras. The supportive crowd of over 200 was composed equally of curious minds and burnouts who still looked to him as an outlaw role model. Crosby sang more strongly than he had in years, offering such staples of his repertoire as “Guinevere,” “Almost Cut My Hair,” “Triad” and “Wooden Ships.” He spiced his between-song patter with some gentle digs at his hosts during his Texas stay.

But midway through the show, Crosby got serious and premiered a song he wrote in jail. “I got loaded for a very long time,” he mused onstage. “I enjoyed it at first, started with a few joints. But when I finished up, I was very unhappy—I got strung out, and it was very hard for me. I’m not gonna preach about drugs—that’s up to each one of you to decide for yourselves. But if you watched my life, you can figure it out.”

Crosby then launched into the only new composition of the evening, a confessional piece titled “Compass”: “I have wasted 10 years in a blindfold/Tenfold more than I have invested in sight.”

While Crosby believed his own songs had special merit, he readily admitted that he was at his best when collaborating. “I love working with other people,” he said. “Right now I live five minutes away from (Graham) Nash, 10 from (Stephen) Stills in Los Angeles. I don’t want to go back and live in Marin County for a while, maybe for good. There’s too much history.”

Crosby’s musical partners had dealt with him in different ways. While Stills had adopted a he-can-take-care-of-himself attitude (“David is David—he’ll be okay,” he said in 1985), Nash was much more involved. “I’ll be there for David whenever he gets out,” Nash vowed while Crosby was incarcerated. “Glass and Steel,” a song on Nash’s Innocent Eyes album that appeared in early 1986, was written for Crosby. The central lyric read, “It’s hard to understand just where you’ve gone/Still hope you find the strength to carry on.”

“He’s the best friend a man could ask for,” Crosby said. “I love him unequivocally.”

Crosby faced the coming years with the zeal of a man who was back on track for the first time in a decade.

“I’m starved for work,” he concluded. “I’m gonna be working all the time, even for fun. I still can’t believe I was that stupid—but I’m proof that it’s never too late to wise up.”

David Crosby passed away on January 18, 2023. He was 81.