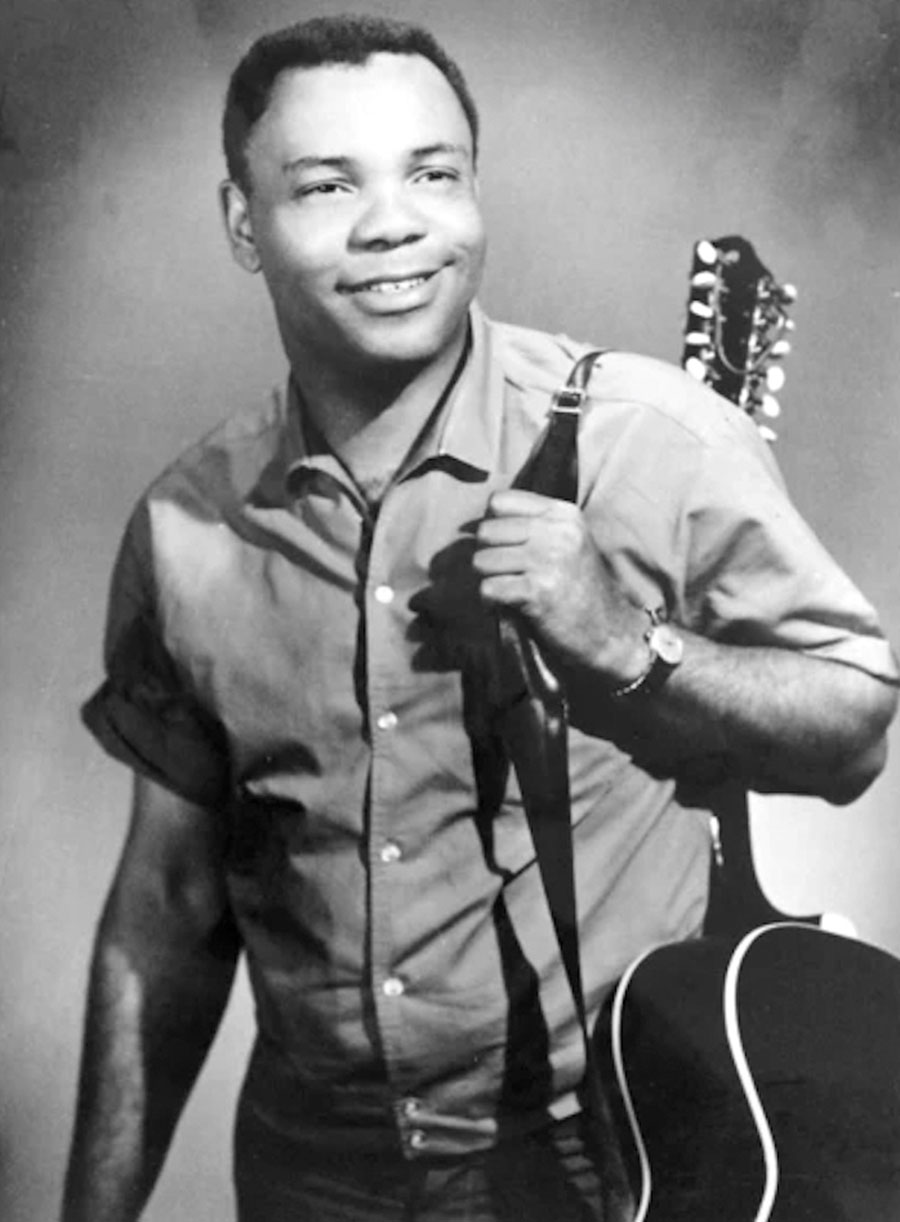

Walt Conley

In Denver’s Fort Logan Cemetery, among the seemingly endless rows of white stones marking the final resting places of military veterans, is one marked “Walter B Conley.” The stele reads “U.S. Navy Korea” and gives his years on earth as May 20, 1929, to November 16, 2003. What it doesn’t reflect is that Conley served most of those years as a Denver-based folk singer of note.

Born in Denver with the given name Billy Robinson, Walt Conley, who was of Black descent, was soon adopted by Wallace and Ethel Conley, a white couple who moved to Scottsbluff, Nebraska. A year after Wallace’s passing in 1944, Walt and his mother moved to Denver’s Five Points neighborhood. After graduating from Manual High School in 1948 he went to Northeastern Jr. College in Sterling on a football scholarship, but didn’t last long due to lack of funds. He returned to Denver and joined the Communist Party in search of racial equality.

While he would eventually renounce his leftist leanings, his character was formed when he worked during the summers of 1948-1950 at a San Cristobal, New Mexico ranch run by folk singer and activist Jenny Vincent and her husband Craig. There, Conley met such musical luminaries as Earl Robinson (composer of “Joe Hill”) and Pete Seeger, who helped him buy his first guitar. Back in Denver, he performed at Denver’s B’nai B’rith in a 1950 program honoring Mayor Quigg Newton for his work in the Human Relations Council.

That December, Conley enlisted in the Navy, where he served as an aviation boatswain’s mate and chaplain’s yeoman. One port of call was New York City, where he was enthralled by the opportunity to meet and see legendary performers Josh White, Cisco Houston and Woody Guthrie. Upon his discharge in 1954, he was involved in the low-budget film Salt of the Earth, which was a failure upon release (reviewers called it simplistic and leftist) but has gained in stature since. Conley then enrolled at Colorado State College (now the University of Northern Colorado) in Greeley, where he graduated in 1957 with a degree in physical education and drama. That year, he performed in civil rights activist Dorothy King’s Showagon, a traveling talent show that appeared in various Denver parks. He then made a six-month attempt at teaching junior high school in Gilcrest, Colorado before quitting to devote his time to folk singing.

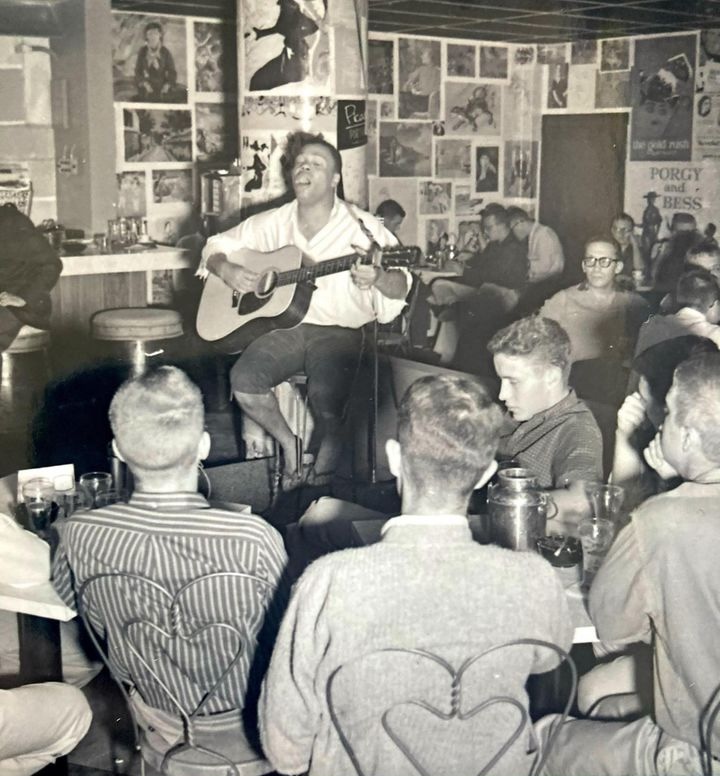

As a Harry Belafonte-styled calypso singer, Conley performed mainly in the bars of the Windsor Hotel at 1802 Larimer St. His appearances there led to other engagements including the Red Ram in Georgetown, where Hal Neustadter saw him and offered an opportunity to play his Little Bohemia club on Lipan Street near 38th Ave. along with another Denver singer—Judy Collins.

When Neustadter opened the Exodus at 19th and Lincoln, he took Collins and Conley with him, which resulted in their appearance on the album Folk Song Festival at Exodus, released in 1959 on Skylark Records. That same year, Conley recorded a 45 for Bandbox Records, “Colorado Story”/“Colorado, Queen of the West,” released with a lavish picture sleeve as part of the tribute to the Colorado gold rush centennial that was taking place. He also waxed “Passing Through”/“Worried Man Blues” for Bandbox.

Conley and Collins worked the same Colorado club circuit, which also included Michael’s Pub (on Pearl St. in Boulder, owned by Mike Bisesi) and the Limelite in Aspen. There, Conley met the young Smothers Brothers, whom he booked for the club he managed for a time at 1920 E. Colfax—the Satire Lounge (owned by Sam Sugarman, a former University of Denver football player). At the Satire, Conley gained lasting notoriety for booking a scruffy Bob Dylan in 1960 and letting him crash at his house on 17th near Williams. Dylan, whom the more polished Smothers Brothers apparently saw as a “faux hobo,” wasn’t popular and was dispatched to play the Gilded Garter in Central City. Upon returning to Denver, he was ostensibly accused of stealing Conley’s record collection before hightailing it out of town.

Conley spent the early ’60s playing around Colorado while Collins leapt to national fame on Elektra Records. He produced two local albums, Passin’ Through with Walt Conley on Premiere Records (1961) and Listen What He’s Sayin’ on Studio City (1963). In addition to standard folk songs (“Joe Hill,” “Hey Nellie Nellie”), the former recording included “The Klan,” an Alan Grey song that reflected Conley’s racial concerns. In a similar vein, he made a spoken-word single for All American Records in 1963 titled “Ballad of the Walking Postman (The Freedom Walk of William L. Moore),” about a white civil-rights protester murdered in Alabama that year.

“My style and presentation were set thirteen years ago when I sang my first song around a campfire in New Mexico,” Conley stated. “That song had a phrase in it—‘A man’s gotta do what a man’s gotta do.’ And I guess what I’m trying to say is I will always be trying to improve, but I set a pattern at that time, and it’s my own.”

Conley hosted a radio show on KDEN for a time and guested on other Denver stations, and he provided the narration and music for the TV show Colorado Legend in 1961. The last half of the decade saw him performing at clubs from New York’s Bitter End to Pasadena’s Ice House.

The ’70s found Conley leaving Colorado and folk music for a time to try his hand at acting. He landed small parts in movies and on television’s Get Christie Love!, The Rockford Files and The Six Million Dollar Man, among other roles. Music proved too much of a lure, however, and in 1983 Conley returned to Denver, where he opened Conley’s Nostalgia. The closing of the south Broadway club in 1987 led to his interest in Celtic music, which he performed regularly at Sheabeen Irish Pub on Iliff and Chambers in Aurora, forming the band Conley & Company.

Conley’s discography from the end of his career lists After All These Years (1991), Conley & Company Do the Sheabeen Pub (2001) and Black & Tans (2002).

Researched and compiled by George W. Krieger