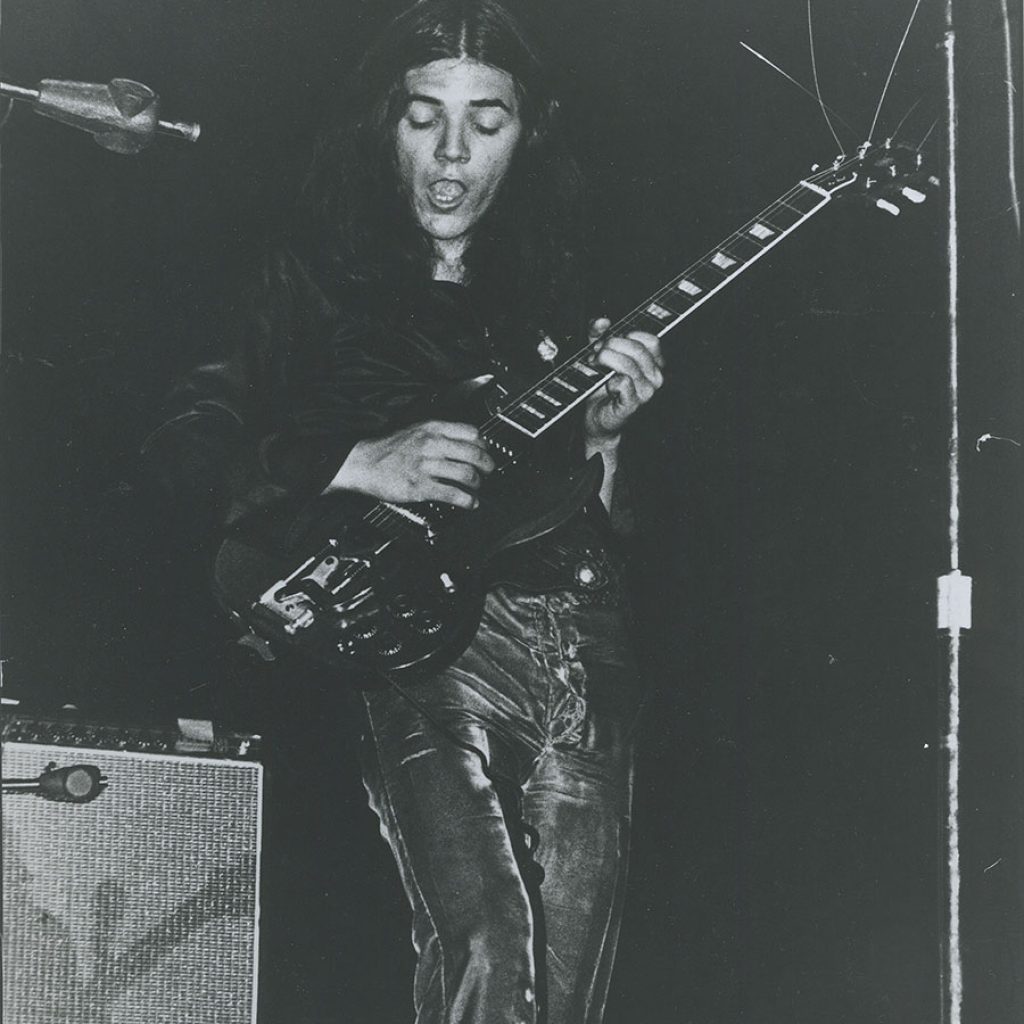

Tommy Bolin

The blinding speed and precision of Tommy Bolin’s guitar work was extraordinary. He was just as adept at silky acoustic stylings and jazz improvisation as he was at hard-rock riffing. Going in to the last half of the 1970s, when Bolin was fast on his way to becoming a rock music legend, some Coloradans felt he could be the next Jimi Hendrix.

Before proving it, the highly talented player died at the age of 25.

After being booted out of high school in Sioux City, Iowa, in 1967 for refusing to cut his hair, Bolin drifted west to Denver. His earliest gig, with singer Jeff Cook in a group called American Standard, was forgettable, but Cook went on to become Bolin’s frequent songwriting collaborator.

Bolin then established a reputation with Zephyr. Colorado’s premier boogie band brought Bolin his first album-making experience (he recorded on two of the group’s three albums) and regularly attracted large audiences to its gigs. There was a huge buzz surrounding Bolin. The era of the guitar hero was dawning, and locals who saw him perform knew he not only played the fastest but he was all over the fretboard.

Bolin blew off Zephyr for a largely unprofitable stint with Energy from 1971 to 1973. Players were Kenny Passarelli, who soon joined up with Joe Walsh; Stanley Sheldon, who went on with Peter Frampton; Max Gronenthal, who established himself with Jack Mack & the Heart Attack and 38 Special; and jazz-rock flutist Jeremy Steig. Other members of Energy included Cook, Tom Stephenson on keyboards, Bobby Berge on drums and vocalist Gary Wilson.

Around 1973, Walsh recommended Bolin for a spot in the James Gang. Bolin penned most of the songs on the group’s Bang and Miami albums, and “Must Be Love” was nearly a smash, peaking at #54 on Billboard’s pop singles charts and reaching the Top 20 in some markets.

During that time, Bolin’s prominence had risen to the point where he also played most of the churning guitar on master drummer Billy Cobham’s Spectrum. The orientation of the jazz-fusion album, particularly a cut called “Quadrant 4,” was monumental—Jeff Beck often credited it as a major influence in sparking his jazz pursuits.

At age 24, Bolin had vaulted into the ranks of electric guitar masters. Everybody believed in him, and he was always able to get what he wanted from people. He left the James Gang in August 1974 “when it was no longer a learning process” and lived off royalties until he signed a contract with hard-rock band Deep Purple, confronting devotees of the departing Ritchie Blackmore head-on.

“To be honest,” Bolin said, “I’d never heard anything but ‘Smoke on the Water.’”

He co-wrote seven of the tunes on Deep Purple’s Come Taste the Band album (#43 in Billboard). Live, he mesmerized fans with the soft, melodic parts of “Owed To ‘G,’” his solo spot.

During that year, Bolin recorded Teaser, his masterpiece. The solo album featured him ripping it up in the company of such diverse talents as saxophonist David Sanborn, drummer Michael Walden and keyboardist Jan Hammer. Teaser explored Latin rhythms (“Savannah Woman”) and reggae along with grinding rock, and it became a full-blown hit—one of the most requested records on the FM airwaves.

Bolin’s period in Deep Purple was a hectic one. On a world tour stop in Indonesia, his roadie was killed in a hotel elevator shaft fall. Returning from the tour, he found himself named a co-respondent in Blackmore’s divorce suit (15 others were also named).

In the spring of 1976, Bolin returned triumphantly to Denver, raising the roof at Ebbets Field. Happy and outgoing, he talked about being a rock ‘n’ roll outlaw, and he spun tales about his appetite for revelry.

“I have the best of both worlds,” he said. “I can make money with Purple and be as artsy as I want on my own.”

After Deep Purple disbanded that summer, Bolin returned to his solo career and launched a fall tour to support his second album, Private Eyes.

Shortly after his band played support at a Jeff Beck concert, Bolin collapsed and died in the bathroom of a Miami Beach hotel on Dec. 4. His body was ravaged by alcohol, barbiturates, cocaine and heroin. According to friends, Bolin had been having periodic problems with drugs and drinking for some time. The pressures that came from being constantly broke and his breakup with longtime girlfriend Karen Ulibarri appeared to have added up to a severe depression.

Bolin was buried in the family plot in Sioux City. Ulibarri put a ring on his finger that Jimi Hendrix had been wearing the day he had died, a gift to Bolin from Deep Purple’s manager that she had been saving for Bolin because he kept losing it.