Rainbow Music Hall

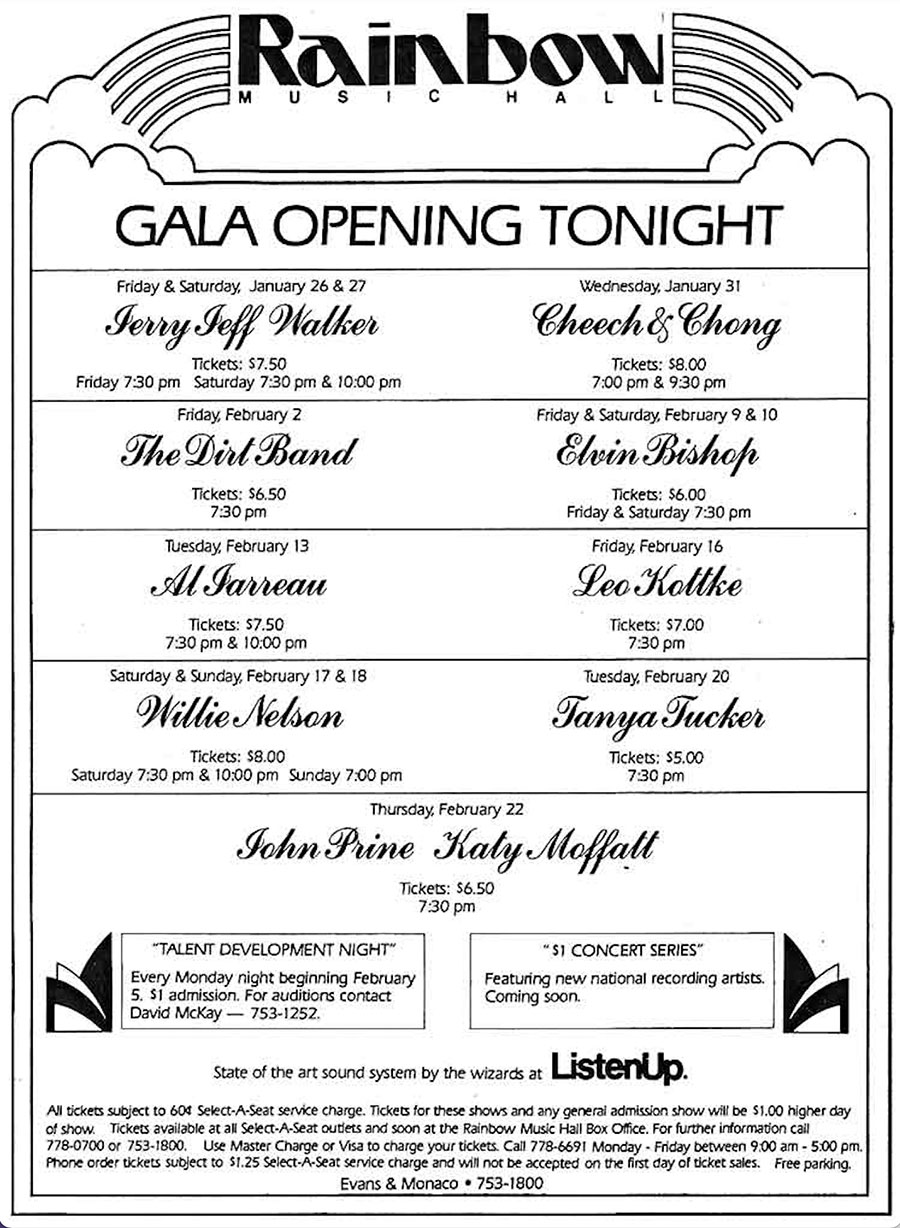

In its original incarnation, the building at the corner of Monaco and Evans in Denver housed a three-screen movie house that failed. The Rainbow Music Hall was born in 1979 when concert promoter Barry Fey had a couple of interior walls knocked down and installed seats in a shallow U-shape around a 42-inch-high stage in the 10,000 square-foot hall. There was a sound booth across the back of the hall and a wide lobby.

After a grand opening gala featuring Jerry Jeff Walker, the Feyline-owned Rainbow became one of the nation’s top music showcases through a lot of work by the concert promotion staff. The Rainbow offered top-notch sound and lighting systems, and the general-admission seating policy usually guaranteed a certain intimacy in the 1,400-seat room. Almost 200 concerts took place at the Rainbow in its first year.

“It was a time when rock music was still in an evolutionary stage,” hall manager David McKay said. “Real bands were building careers—they had gotten together and figured out that they could write and perform good stuff together, and they went on tour to sell records. Fans couldn’t wait to get their hands on the new album or see them perform. Two or three dollars for a ticket to see Talking Heads or Blondie or U2? I don’t know how that could work today. Now it’s how fast can you make a buck.”

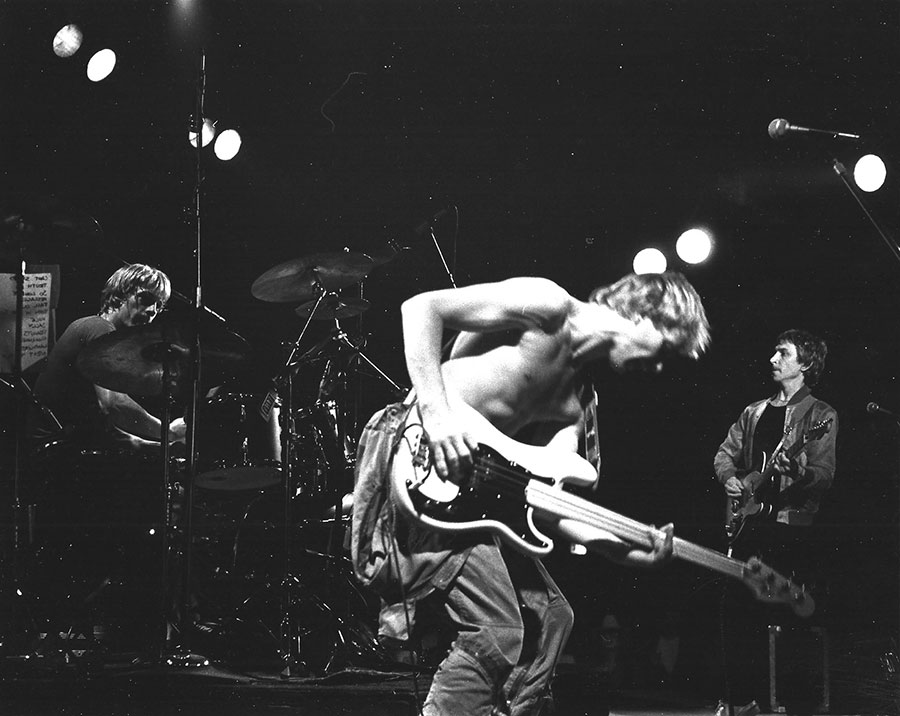

The Rainbow legend was built by the acts that graced its stage, a spot to catch soon-to-be superstars on the way up. U2’s first two appearances served notice that they wouldn’t be denied an audience, even though area radio stations initially wouldn’t support their music. A trio called the Police, crossing the country in a station wagon, arrived at the Rainbow in 1979 to promote a ditty about a prostitute named “Roxanne.” There were Rainbow shows by Pat Benatar (1979, 1980), John Cougar (1980), Pretenders (1980, 1983), Talking Heads (1979), Hall & Oates (1979) and Eurythmics (1983)—all acts that went on to tour the nation’s largest arenas.

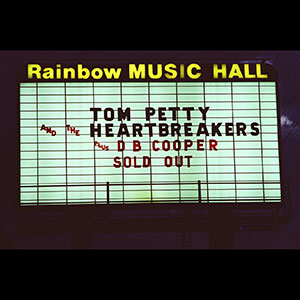

Over the years, already famous artists like Willie Nelson and Journey took advantage of the Rainbow’s intimacy. Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers snuck into the Rainbow for a show after a performance at Red Rocks. Barry Manilow booked the venue for a “dress rehearsal performance” so he could practice before gearing up a nationwide tour of big halls.

When Rainbow management was offered a last-minute Benatar date on the second night of Bob Dylan’s three-night stand in 1980, the crews executed a feat that was legendary in the industry—they pulled Dylan’s gear offstage and set up Benatar’s, then tore hers down and reloaded Dylan in time for a special midnight show. The year before, Journey was scheduled for two shows. The first began at 7:00 p.m.—even though the equipment truck was snowed in on Vail Pass and didn’t arrive until 6:30 p.m.

The best costumes in Rainbow history belonged to Nig Heist, a band composed of roadies for Black Flag. When they opened for the Flag in 1984, they took to the stage wearing nothing but their guitars and proceeded to simulate acts of sexual congress among themselves. Runner-up was Prince, who cavorted onstage in a G-string and trench coat for his “Dirty Mind” performance in 1980.

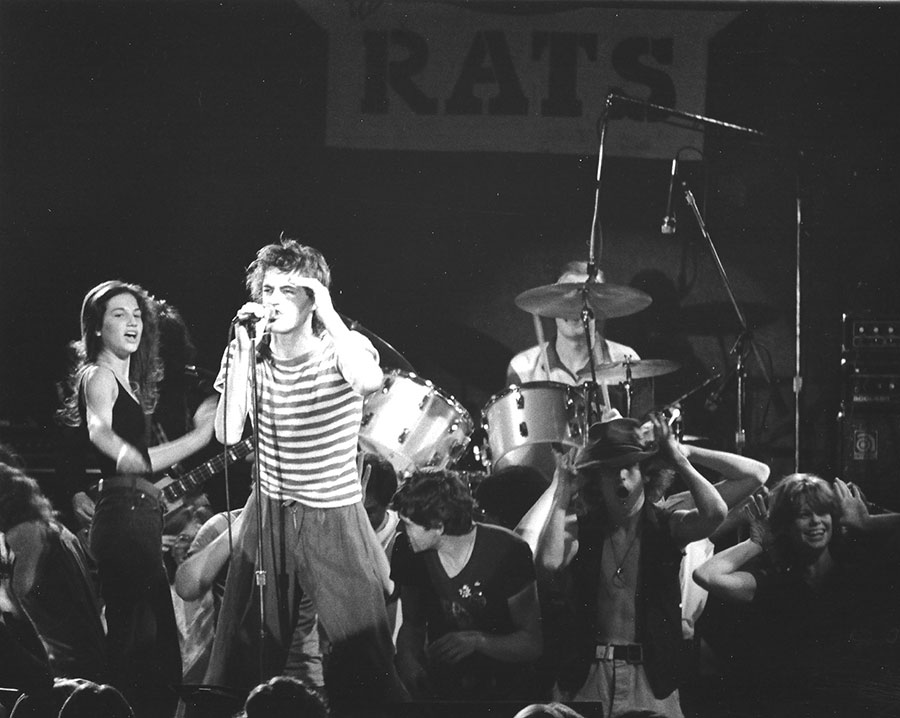

Most of rock’s new wave bands stopped at the Rainbow, including Blondie and the Ramones. Joe Jackson played sitting on a stool with his leg in a cast. The Boomtown Rats, led by Bob Geldof before his Live Aid/“We Are the World” gig, delivered a memorable show that belied their ultimate lack of acceptance in America.

Devo arrived on the Fourth of July in 1979 and started griping about the accommodations, so the Rainbow staff went out and bought a Hibachi grill and held a holiday barbecue picnic in the parking lot.

The funniest shows? A tossup among Robin Williams, Cheech & Chong and Andy Kaufman. The most disparate audiences? When Rick Springfield played the Rainbow during his General Hospital heyday, little girls packed the matinee—and little girls’ mothers packed the evening show.

The venue closed in 1989 and was turned into a Walgreen’s drugstore.