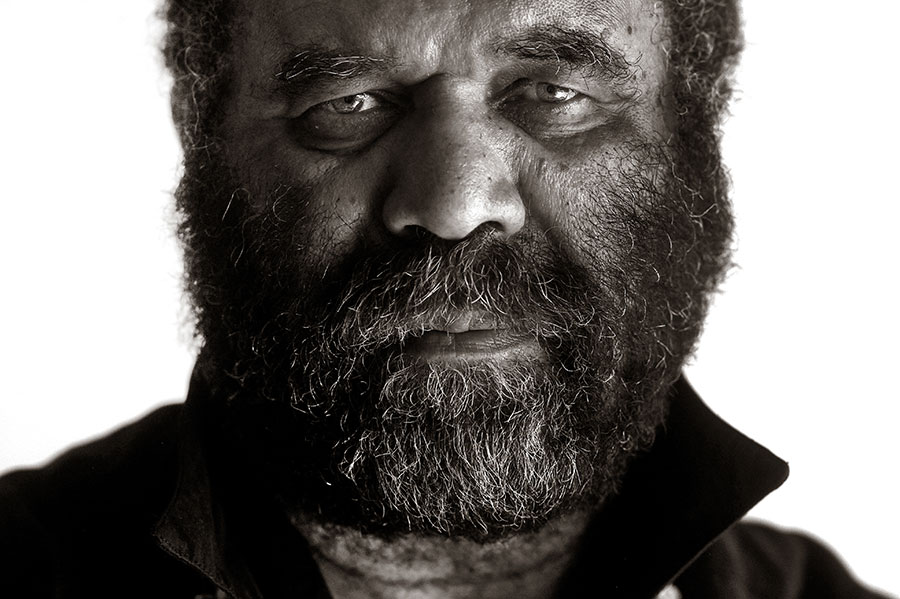

Otis Taylor

Curiously, the 2002 winner of the prestigious W.C. Handy award (the blues equivalent of the Grammys) for Best New Artist was a 53-year-old man who began playing as a teenager in the 1960s. But there are no overnight success stories, and writers and performers of Otis Taylor’s caliber hardly come out of nowhere.

Born in Chicago, the son of a railroad man, Taylor grew up in Denver after his family relocated, motivated by an uncle’s murder. An adolescent Taylor began not only listening to music but aching to create it. He spent afternoons and weekends at the Denver Folklore Center, where he bought his first musical instrument, a used ukulele. Next up was a banjo.

“All the instructors taught me how to play music during their breaks—I never had to pay for a guitar lesson,” Taylor said. “I already had an attitude about being different. I was making sandals back in ‘64 way beyond when that hippie stuff started up—that all came out of the folk scene that I was hanging out with.

“At home, we were what some people might call a little eccentric. I’m ‘first-generation hip’— I was raised in an environment that was too hip, sometimes. My father was a big jazz buff, and he loved that be-bop lifestyle—start partying Thursday night and go on until sometime Sunday.”

Taylor began playing folk blues after meeting such masters as Son House and Fred McDowell. By the time he drifted to Boulder, he had already led a couple of groups. He managed to save enough money to travel to London in 1969, where a brush with Blue Horizon Records lasted only a few weeks.

“They didn’t get what I was doing over there,” Taylor said. “I ran out of money. They wouldn’t give me any, so I came back home. I was homesick anyway.”

Back in Boulder, he hooked up with Tommy Bolin, who was on the rebound from the personnel changes and business chaos that surrounded Zephyr. However, Taylor retreated from the music business in 1977. During a sabbatical that lasted almost two decades, he did not perform in public, preferring to refine his gruff vocals and technique on guitar, harmonica and banjo. He became a successful antiques dealer and then organized one of the first all-black bicycling teams.

In 1995, a friend and long-time investor in Taylor’s bicycle racing team opened Buchanan’s, a coffeehouse on the Hill in Boulder, and decided he wanted to do live music in the basement. “He asked if I could put a band together for the opening,” Taylor said. “All of a sudden, I was back in again.”

Taylor and his accompanists, longtime friend Kenny Passarelli (whose resume included stints in the 1970s with Elton John, Dan Fogelberg, Stephen Stills and Joe Walsh) on bass and Eddie Turner on venomous and ethereal lead guitar, played together and found their sound—a drumless yet driving groove, reminiscent of John Lee Hooker’s one-chord boogie—was too “cool” and uneasy to disregard. Some called it “trance blues.”

Taylor’s scary, stinging style relied little on the standard 12-bar blues structure and “woke-up-this-morning” lyric clichés. Besides thoughtful, vivid first-person storytelling, Taylor applied fables and allegories from distant times and places. In a breathy style, he talked-moaned his dark vignettes. Some of them touched on the pain and misery of romantic infidelity, but most were peppered with vitriolic social commentary about the African-American experience.

Taylor self-released Blue-Eyed Monster, a mini CD. It caught just enough critical acclaim to convince him to record a full-length CD, When Negroes Walked the Earth. He sang about the lynching of his grandfather on his 2001 follow-up, White African, and the buzz eventually landed him some national exposure, leading to his four 2002 Handy nominations. He’s released a steady cavalcade of intriguing, critically acclaimed albums—Respect the Dead, Truth Is Not Fiction, Double V, Below the Fold and Definition of a Circle. Augmenting his band on several songs were Ben Sollee’s evocative cello lines and the background vocals of his daughter, Cassie.

The Boulder resident sees the blues as a forum for more than just good-time boogie. Through his “Writing the Blues” program, he’s been sharing the genre’s history and heritage. “I’ve done it for elementary schools, and I’ve done it for universities. If I don’t get the young kids involved, I won’t have an audience. You have to do it on an emotional level, not just an intellectual level. I have them write the blues on paper and sing or speak it. Once they understand that everybody has the blues, they can relate to it.”

The revelatory Recapturing the Banjo appeared in 2008, a mission statement to present the banjo in a clearer historical light; the banjo was originally an African instrument, arriving in the New World via the slave trade and turned almost exclusively into a white bluegrass instrument. Pentatonic Wars and Love Songs, released in 2009, was a dark and jazzy examination of the power and complexity of desire beyond mere romance, much bleaker than easy love/dove/above rhymes.

Taylor has toured in clubs and at festivals, achieving arguably more prosperity in Europe than in the States, in some respects mirroring the traditional blues success overseas.

“When I stopped writing songs in the ’70s, psychologically, I went to sleep like Rip Van Winkle and then I woke up,” Taylor said. “When I was a kid, everybody always wanted to turn somebody on to new and exciting music—I thought the whole thing was about discovering people. That attitude was dangerous for my career when I came back to music. It was a whole new industry—it got commercial. For the first few years, it caught me off guard. I had to readjust. I had the energy, but I was naïve. I pissed off a lot of people. I got a reputation for being snobby.

“I still don’t have much of a reputation for playing in Colorado. You talk to a musician, they’re always saying how they get no credit in their hometown. The soul of humanity is the arts, and people turn their back on their own community. It’s backward—it should be the community that rallies behind you. When somebody says you can’t be a prophet in your own land, well, that’s somebody not paying attention to their own land.”

Taylor continued to bring a spellbinding intensity to his music. Taking the easy route never appealed to him.

“I rode a unicycle to school when I was 16, and there were not a lot of black rugby players, either,” he said. “No matter what I do, I’m just a born outlier.”