Mammoth Gardens

It’s ironic that the current generation of Colorado music fans know the venue at 1510 Clarkson in Denver as “The Fillmore.” Back in the early Seventies, the Romanesque two-story structure with arched windows and twin domed towers enjoyed notoriety as Mammoth Gardens—an erstwhile roller rink, dancehall and warehouse that was supposed to compete with the Fillmore Auditorium, Bill Graham’s counterculture concert mecca in San Francisco.

Such were the aspirations of Stuart Green, a law-school dropout from New Jersey, who purchased the building in 1969. He reportedly spent $50,000 to refurbish the place and dropped another $13,000 on a sound system.

With Denver affording few venues for live rock and roll, Green clearly saw an opportunity. Yes, there were the Auditorium Arena at 13th and Champa and the Coliseum off I-70 on Humboldt—both of which had sound quality better suited to circuses than Stratocasters—and Red Rocks Amphitheatre up the hill in Morrison. But that iconic venue, renowned for its acoustics, had mostly resisted booking rock shows after riots marred a 1962 Ray Charles concert and a 1968 Aretha Franklin concert.

The closest the Mile High City had come to a hippie rock club was the Family Dog at 1601 West Evans Avenue. A spinoff of Chet Helms’ San Francisco venue, it opened in September of 1967, only to be hounded out of existence by the older establishment less than a year later—but not before showcasing such groundbreaking talents as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jefferson Airplane, the Grateful Dead, Cream, Buffalo Springfield, the Doors and Canned Heat, whose members’ arrest on specious drug charges precipitated the Dog’s demise.

Looking to attract bands of that caliber, Green hired Barry Fey, who’d booked them at the Family Dog, to do the same at Mammoth Gardens. The Festival Group of Philadelphia handled the sound, and Marty Wolff, who would have a long career as a music promoter, served as stage manager. Wider than it was deep, the sparsely decorated Mammoth Gardens could hold approximately 5,000 people, and ticket prices averaged around $3.50.

On April 17, 1970, Mammoth Gardens opened. As a wet spring snow fell, fans waited outside for hours for the first of two nights featuring Clouds, the Denver-based Zephyr and headliner Jethro Tull. Playing mostly music from Benefit, Tull reportedly put on an outstanding show, while Zephyr’s Tommy Bolin’s gutsy guitar work whipped the crowd into a frenzy. One member of that crowd, Dan Campbell, remembers the room configuration creating an intimate, electric atmosphere enhanced by a superb sound system.

A week later, John Hammond opened for the Grateful Dead, whose loyal fans still trade tapes from those April 24 and 25 shows. Deadheads also recall the power being turned off twice, forcing the band to cut its performances short.

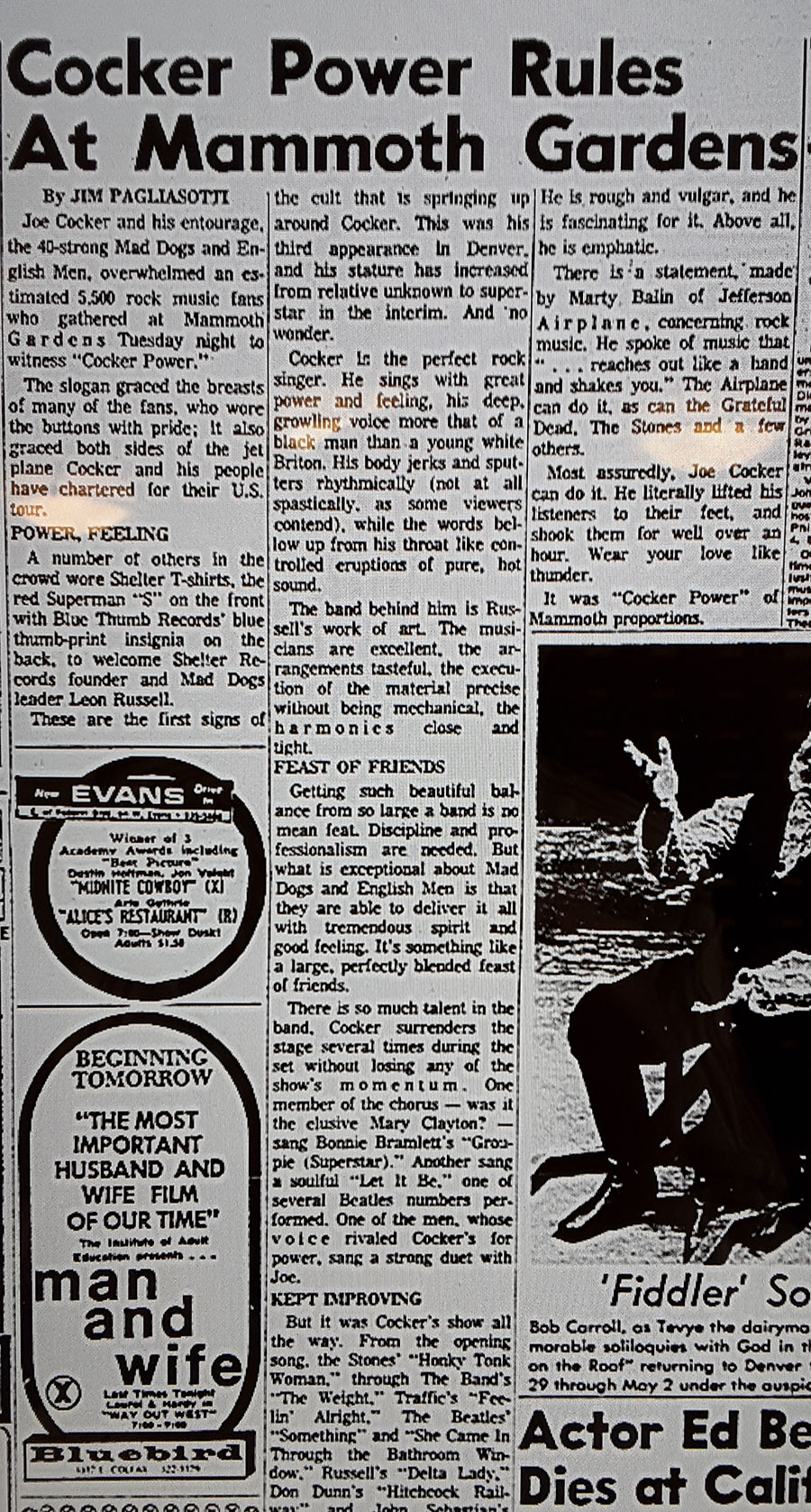

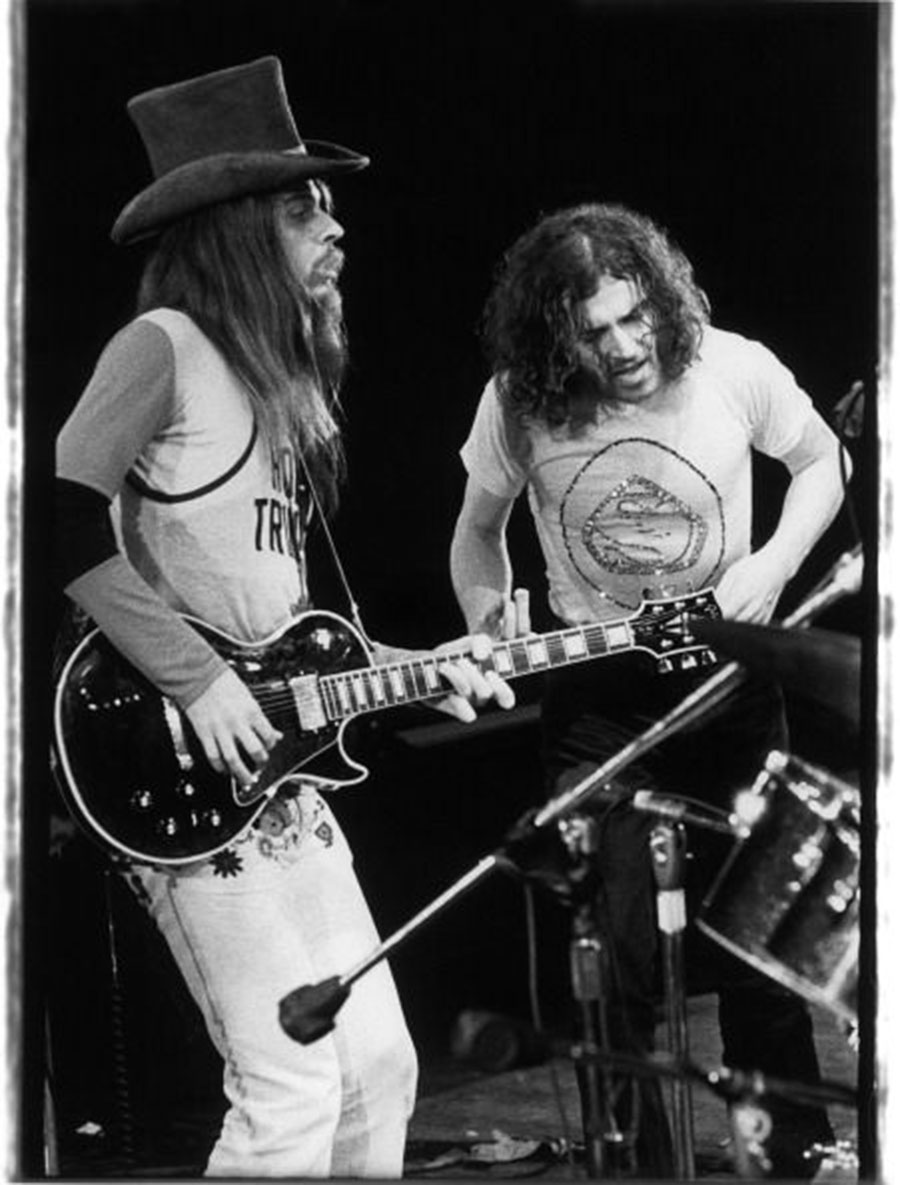

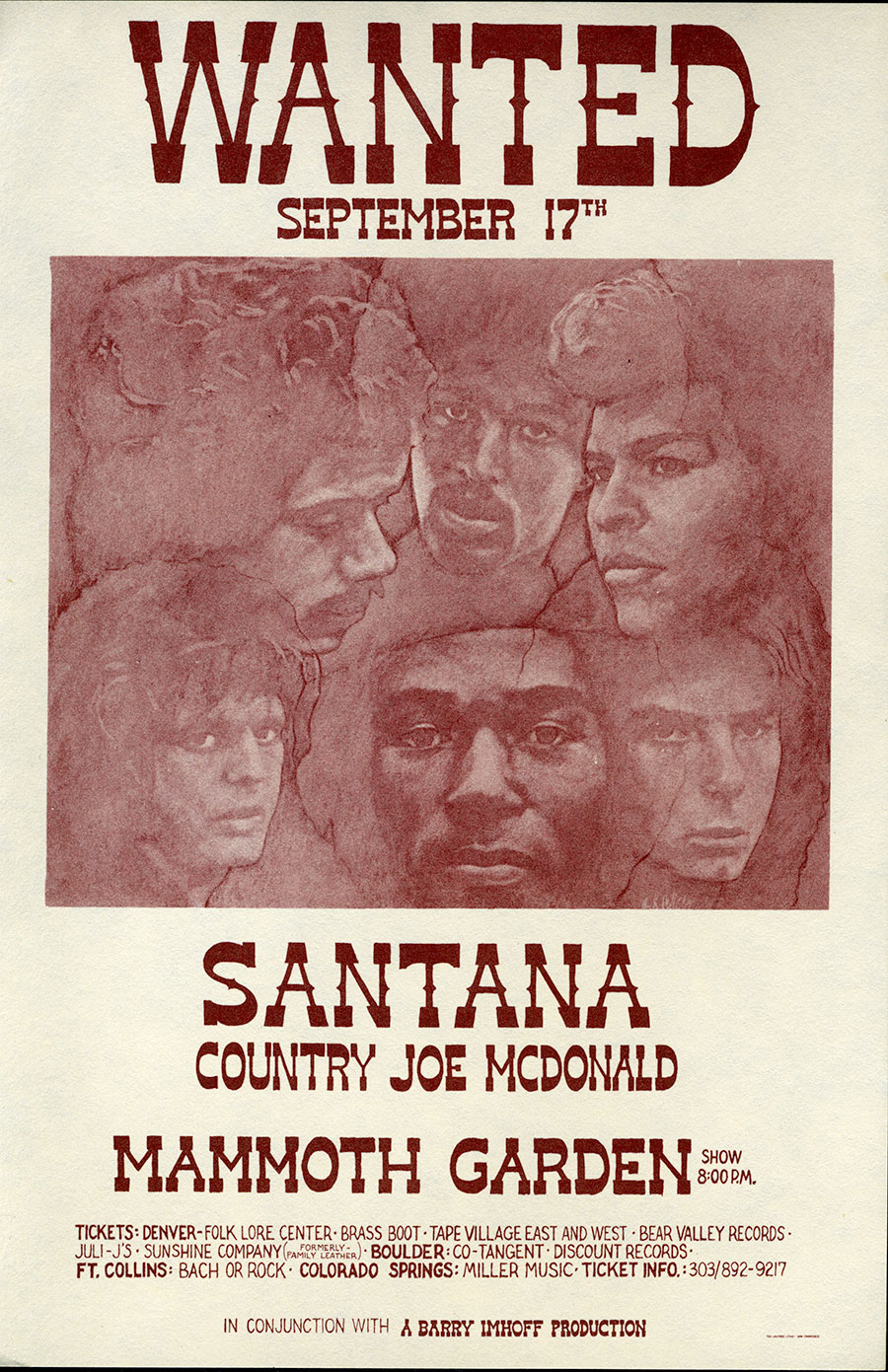

Like the Family Dog, Mammoth Gardens became the hub for the hottest performers. In addition to Tull and the Dead, Joe Cocker, Mountain, Procol Harum, Santana, Van Morrison, Johnny Winter, Leon Russell, Linda Ronstadt, Steve Miller Band and dozens of others sold out the venue.

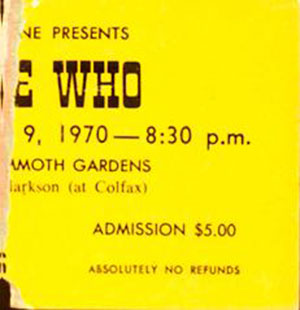

The popularity of Mammoth Gardens became problematic, however, as the weather grew warmer, as the building, built in 1907, lacked decent ventilation or air conditioning. When the Who, fresh off the success of Tommy, came to town for a June 9 concert, the heat in the room necessitated capping attendance to the first 3,500 of the 5,000 ticketholders, with the remaining 1,500 joining 2,000 others at an added show the following night.

With the stage temperature for the opening act, Sugarloaf, exceeding 100 degrees, the staff opened the giant west-facing windows for the Who, whose decibel level, according to Sugarloaf band members Rob MacVittie and Bob Webber, was akin to standing at the outlet of a jet engine. The Who played their hits before launching into the entirety of Tommy. When Roger Daltrey sang, “Tommy can you hear me?” people a mile away in Civic Center Park could answer in the affirmative.

Mammoth Gardens soon felt a different kind of heat—that of the Denver Police Department. Ultimately the same forces that conspired to shutter the Family Dog closed in on the Capitol Hill concert venue.

After a June 26 Iron Butterfly concert, the entire vice squad converged on the area, with the city’s District Attorney Mike McKevitt calling for Mammoth Gardens’ closure as “one of the largest juvenile delinquency problems in the city.” He claimed residents were unhappy with the noise, there was widespread use of marijuana, curfew violations were unmanageable, businessmen were losing trade and pedestrians were frightened by a “permanent hippie population.” East Colfax in general was degenerating, he claimed, and “unless something is done about it, the town’s going to hell in a handbasket.”

That Halloween’s Steve Miller Band concert was the last under the aegis of Stuart Green. Although attendance was high at the shows, problems with ventilation, parking, the police and the neighbors ultimately led to fines and the premature ending of another pioneering Denver venue after only seven months of existence.

The ensuing 15 years saw a number of occupants: a farmers’ market, Major Indoor Soccer League games featuring the Denver Avalanche, occasional concerts and numerous transients from the adjacent Clarko Hotel.

In 1986, after a period of closure, Manuel and Magaly Fernandez reopened it as the Mammoth Events Center. For the next 13 years, they staged multicultural concerts and dances, and brought in national touring acts like Rickie Lee Jones, the Brian Setzer Orchestra and Rick James, who after his 1998 show suffered a stroke in his hotel—a victim of what doctors called “rock ‘n’ roll neck” due to “repeated rhythmic whiplash movement.”

By then, James wasn’t the only one hurting. The Mammoth Events Center owed more than $1 million in loans to the Colorado Housing and Finance Authority. In 1999—30 years after Stuart Green had envisioned a Denver concert venue to rival Bill Graham’s Fillmore in San Francisco—Bill Graham Presents bought the building, invested in major upgrades and renamed it the Fillmore.

Bill Graham Presents later merged into Live Nation. For the last two decades, the Fillmore has become a musical mainstay, drawing acts such as Widespread Panic, Foo Fighters and Morrissey—and in the process fulfilling a destiny that first took shape during seven rocking months in 1970.

By Jon Rizzi and George Krieger