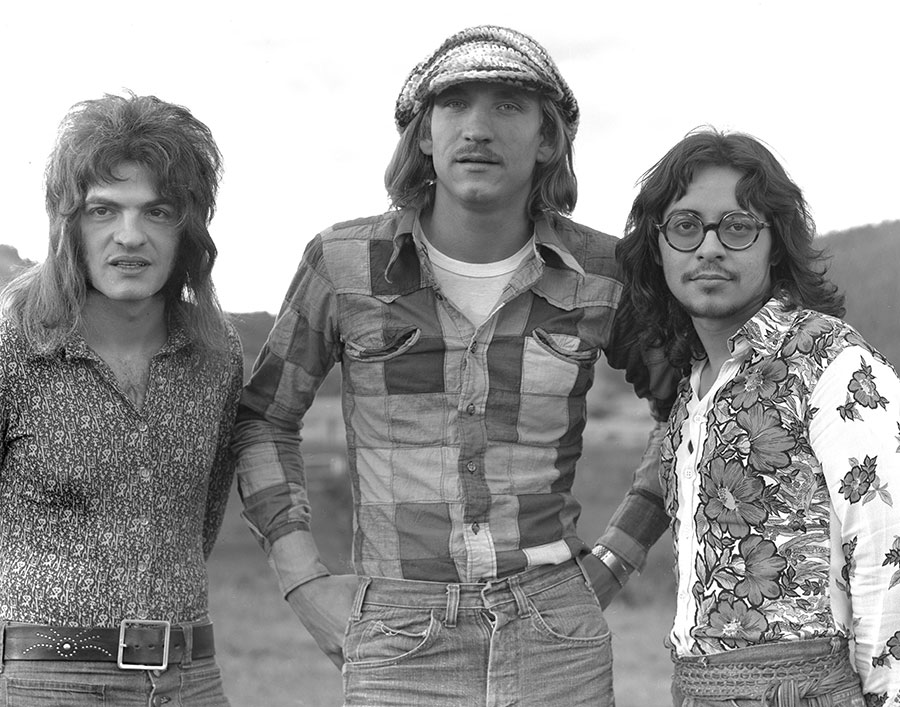

Joe Walsh/Barnstorm

“Rocky Mountain Way,” the classic-rock nugget, is Joe Walsh’s signature tune.

“It’s about living in Colorado, having left Cleveland and the James Gang and having no regrets at all,” Walsh said.

Born in Wichita, Kansas, Walsh began playing guitar in junior high school after watching the Beatles on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in 1964. He built a considerable reputation as lead guitarist and lead vocalist for the notorious Cleveland-based James Gang. Such Walsh tunes as “Funk #49, “Tend My Garden,” “Walk Away” and “The Bomber” redefined the sound and concept of the power trio, earning high critical praise and three gold albums.

The success of the James Gang brought wide popularity and endless touring, and, as the big bucks beckoned, Walsh turned the other way. In 1971, Walsh made the difficult decision to leave the James Gang and relocate to the open air of Colorado’s Boulder County.

“I didn’t get much help from my management or record company at the start of pursuing a solo career,” Walsh said. “Moving to Colorado had a lot to do with my friendship with Bill Szymczyk, who at that point was an advisor helping me feel confident because I was scared to death.”

“The James Gang was on tour and played Denver,” Szymczyk recalled, “and Joe hung out with me and saw the Tumbleweed Records offices on Gilpin Street and what we were doing and said, ‘This is kinda nice here.’ He was making noises about quitting the band and starting his own solo career. I said, ‘Well, if you do, move here.’ He said, ‘Okay!’”

For months Walsh lived in the mountains and practiced ham radio operations. Full-time exposure to the rural landscape and easygoing, rustic lifestyle in the small towns of the Rockies seeded a new perspective.

“I took an amount of time off and began forming an arrangement of players conceived in a way to express what I was hearing and what I thought a band should be,” he said. “They were strange times and it was hard, but it took me back to basic survival, which is always very positive in terms of creative energy. When you have to get yourself together, you play differently from when you’re rich.”

Walsh emerged with full force in 1972, forming a new group called Barnstorm with an old colleague and a newfound friend. Joe Vitale, a confrere from their lean-and-hungry days at Kent State University and a refugee from the band Amboy Dukes, was five-foot five-inches of talent and energy on drums, tympani, gong, flute and synthesizer. Bassist Kenny Passarelli hailed from Colorado and provided a perfect complement to the music Walsh was bent on creating.

Barnstorm was the first album ever recorded at Caribou Ranch, the facility high above Boulder that would soon gain fame as a destination studio. A long winter and spring at Caribou served Walsh and his band; Szymczyk handled the production and took care of the mixing.

“When Joe and I were getting ready to do his first solo record, I had heard rumors of Jimmy Guercio’s Caribou ranch,” Szymczyk said. “So of course I wanted to suss him out and see what was going on. Guercio was going to direct a movie, Electra Glide in Blue, starring Robert Blake. He said, ‘I’m not going to finish the studio because I’m not going to be here for six months.’ We begged and pleaded with him. We definitely wanted to record there because it was only three miles from Joe’s house. We thought it would be good if we could break it in for Guercio while he was off making a movie, so he finished the room for us.

“But the downstairs was still dirt floors, there was no bathroom, and upstairs was two-by-fours. We used the studio, but it was a lot of DIY stuff.”

The studio became their playground. Walsh moved away from the hard rock sound of the James Gang and explored his love of lushly textured production, and he freely indulged himself with spacy, open-ended songs. Passarelli and Vitale proved themselves adept at handling Walsh’s beautiful choruses, country tinges and pastoral pop hooks. He experimented with running his guitar straight into a Leslie 122 to get swirly, organ-like guitar tones, and he utilized the ARP Odyssey synthesizer to great effect on such songs as “Mother Says” and “Here We Go”; the music ranged to the lone hard rock track on Barnstorm, “Turn to Stone.” Barnstorm was a critical success. Record World found the album of laid-back fantasia “oh-so-tasteful” while Cash Box applauded the “genius arrangements” and “stunning harmonies.” The stage held its own magic, and Walsh built a larger Barnstorm band for the road, adding keyboardist Rocke Grace and later Tom Stephenson.

Accompanied once again by Passarelli and Vitale, Walsh officially went solo the following year with his second album, The Smoker You Drink, The Player You Get—its title growing evidence of his comic persona. It was a commercial breakthrough. Recorded at Caribou Ranch with Szymczyk producing, the album became the first Top 10 hit of Walsh’s career; it went on to sell more than a million copies. Two songs received heavy airplay and opened up a massive audience for Walsh and his band—“Meadows” and “Rocky Mountain Way,” the latter inspired by Walsh’s move to Colorado. Co-written by Passarelli, the song was a perfect vehicle for his soaring slide guitar work and distinctive reedy tenor.

“I always felt ‘Rocky Mountain Way’ was special, even before it was complete,” Walsh said. “We had recorded that before I knew what the words were going to be, but I was very proud of it. That was pretty much one shot at it, all playing at the same time.

“I got kind of fed up with feeling sorry for myself, and I wanted to justify and feel good about leaving the James Gang, relocating and going for it. I wanted to say, ‘Hey, whatever this is, I’m positive and I’m proud,’ and the words just came out of feeling that way, rather than writing a song out of remorse. It turned out to be a special song for a lot of people.

“It’s the attitude and the statement. It’s a positive song, and it’s basic rock ‘n’ roll, which is what I really do.”

Barnstorm disbanded amicably in 1975, allowing Walsh to produce Dan Fogelberg’s Souvenirs album and to work at a less hectic pace on his third solo album. So What included the songs “Welcome to the Club” and a remake of “Turn to Stone.” During the recording of So What, Walsh invited members of the Eagles to contribute background vocals. Walsh played on albums by such artists as Stephen Stills, Ray Manzarek, Keith Moon, Michael Stanley, America and Rick Derringer.

Colorado was where Walsh experienced some of his greatest musical triumphs—and a great personal tragedy when his daughter Emma died in a car accident. A simple plaque adorns the water fountain in North Boulder Park, her favorite play spot, donated by Walsh and former wife Stefany: “This fountain is given in loving memory of Emma Walsh. April 29, 1971 to April 1, 1974.”

“Joe was on the road constantly, and when he’d get off he’d spend more time in L.A. than he would in Colorado,” Szymczyk said. “When Emma died, that put the period on the whole deal. Stefany went to pieces, and so did he, and so did I—I was her godfather, in the hospital when they had to take her off life support. That was a very dark time. Very shortly after that, Joe was permanently gone from Colorado.”

At the end of 1975, Bernie Leadon departed the Eagles, who, facing a tour of Australia and the Orient, drafted Walsh to join them. That led to a full-time collaboration between Walsh and the hugely popular West Coast country-rock quintet. Walsh’s addition gave the band a much-needed harder-edged sound, most notably on Hotel California, their biggest selling album, on which he co-wrote the hit “Life In the Fast Lane.” Walsh’s Eagles tenure gave him enhanced visibility, and he continued his pattern of successful solo albums.

Walsh remains one of the most colorful characters in rock music. Passarelli played with a variety of musicians, including Elton John, Dan Fogelberg, Stephen Stills and Hall & Oates. Vitale continues his longtime partnership with Walsh; he also appeared with Fogelberg, the Eagles and Crosby, Stills & Nash.