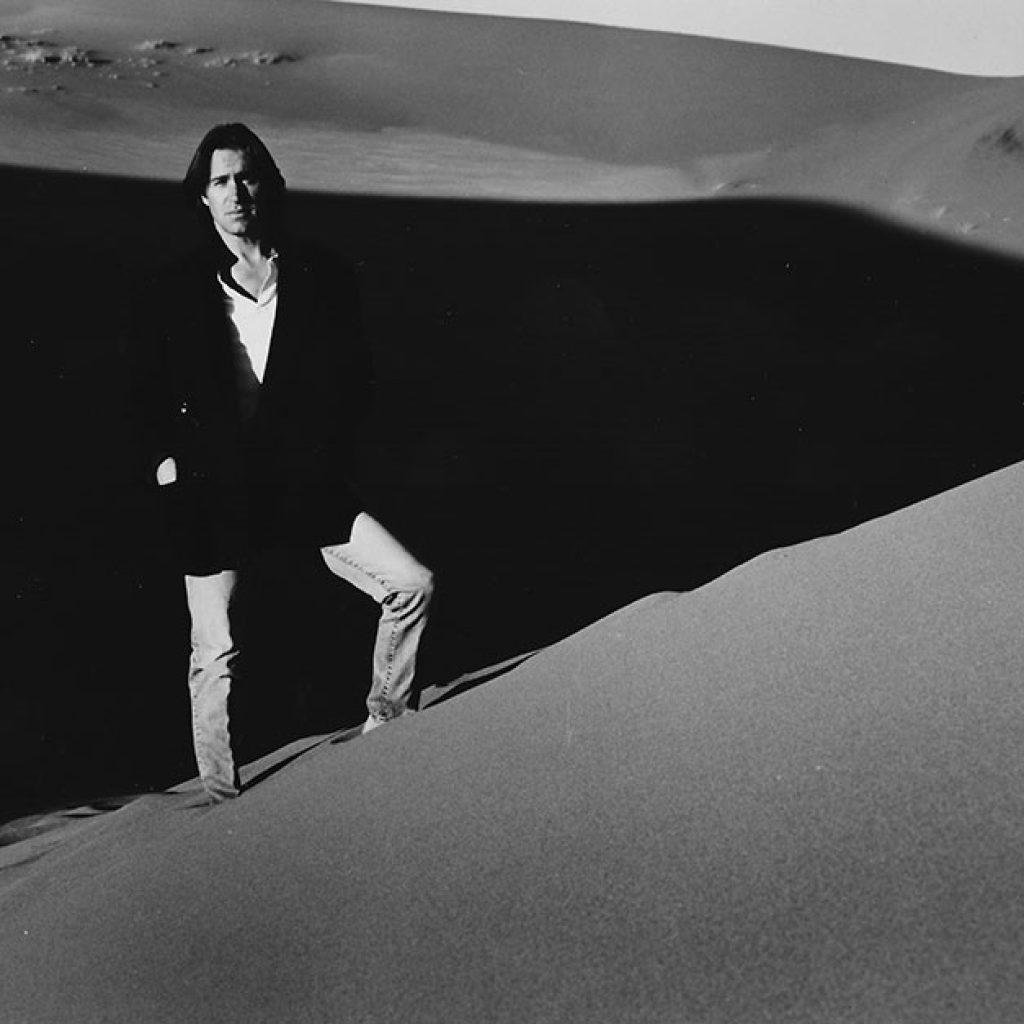

Dan Fogelberg

He went from being a Midwestern singer-songwriter to an established international star. But Dan Fogelberg ultimately settled in Colorado—a fitting destination for “a quiet man of music,” to quote one of his best-known lyrics.

“It’s a pretty calm existence here. I’m not a very social person,” the notoriously reserved Fogelberg said. “I cherish my privacy, and I don’t want to give anything away. My private life is separate from my musical life.

“I’m an avid skier during the winter, and I prowl around the state. Summertime, there’s so much to do. I enjoy the solitude of hiking and mountain biking. The mountains have always been a very healing place for me. You go through a lot of changes in life, but these mountains will always be here.”

Born in Illinois, Fogelberg was facilitated and supported in his musical growth by his father, Lawrence, a bandleader and high school band director, and his mother, Margaret, a music instructor.

“It’s certainly no accident that my parents were both trained musicians,” Fogelberg stated. “The music has to come from somewhere. My mother was trained to sing opera, but she decided to have a family, so my dad was the musician in the family. Music was always around, and that was great. I was raised on classical music—I didn’t understand it, and I didn’t necessarily even like it, but I was exposed to it.”

He grew up playing in garage bands and, while studying painting at the University of Illinois, realized music was the main focus of his creative talent. He left school to follow that muse and headed for the West Coast, finding inspiration during a week in Colorado before moving on. Under the aegis of his manager, Irving Azoff, Fogelberg secured a recording contract. His first album, Home Free, was recorded and produced in Nashville by Norbert Putnam.

For his second release, Souvenirs, Fogelberg enlisted producer Joe Walsh, who had recently recorded at Caribou Ranch in Colorado. With Walsh’s help, Fogelberg expanded on his sparse, countrified folk sound. His growth as a songwriter was most evident on “Part of the Plan,” a buoyant, radio-friendly hit single that catapulted him into the commercial firmament at the height of the California rock explosion alongside such hit makers as the Eagles, Jackson Browne and Joni Mitchell.

While touring through Colorado in the mid-1970s promoting Captured Angel, his third album, Fogelberg learned that a mountain house was on the market. He fell in love with the Nederland spread and bought it from one of his favorite musicians, Chris Hillman, who played with the Byrds, the Flying Burrito Brothers and Manassas. He flew to his Nashville farm to pack up his belongings and hurried back to his Rocky Mountain hideaway. He plunged into a season of solitude and composing, and it resulted in the songs for his next album, Nether Lands. Writing in a more ornate and elaborately conceived idiom, it brought together his from-the-heart lyrics with lightly harmonized rock, pop, country and folk ideas with vestiges of classical influences.

“I grew up with that album,” Fogelberg said. “When I made Nether Lands, I didn’t feel like I was imitating anyone, paying tribute to my influences like the Beatles and Buffalo Springfield. Suddenly it felt like, ‘This is my music, this is what I’m about.’

“When you discover your own voice, it’s so incredibly exciting that you never want to let go. Ever since then, it’s been a constant unfolding of what I’m capable of. For better or worse, sometimes you go down paths that aren’t as good as others. But it’s important to be receptive. Once that fire is set in you, I don’t know that you can ever extinguish it.”

Nether Lands went platinum, and Fogelberg’s signature sound endeared him to a loyal legion of fans. He’d write and record constantly, cutting tracks at Caribou Ranch and Boulder’s Northstar Studio. He recorded part of his next venture, Phoenix, in Colorado, and the songs “Heart Hotels” and “Longer” went to the top of the charts. The public perceived Fogelberg as a mere “sensitive balladeer,” but he owned up to the lyrical leanings that earned him that tag.

“I’ve always been in touch with something that I write,” he allowed. “I feel experiences deeply, and I have an outlet, a place where I can translate those feelings. A lot of people go to psychoanalysts. I write songs. It really isn’t a reflection of my total being, though. I mean, I don’t like being called an ‘aching heartbreak kid’ because I’m just not that way. I’ve written some sad stuff in my life, but I’ve written some uplifting songs.”

The Innocent Age, an autobiographical concept album released in 1981, spun off four of his biggest hits—“Same Old Lang Syne”; “Hard To Say”; “Leader of the Band,” a tribute to his musician father; and “Run For the Roses,“ an unofficial theme for the Kentucky Derby.

At any given moment, ace balladeer Fogelberg was more eager to follow his muse than to write more pop hits and follow the external standards of the music world. That was never more obvious than in 1985, when the Colorado-based bard released the change of pace High Country Snows.

“The Innocent Age was so personal that I didn’t want to deal with that anymore. I dug real deep on that one, so I wanted to see what other types of songwriting I could do.”

By 1980, Fogelberg had bought land outside of Pagosa Springs on the western slope of Colorado, where he constructed a house and barns. During the many hours spent driving his truck back and forth to Boulder, he listened to a lot of bluegrass tapes, feeding his desire to play some roots music again. After sitting in with Chris Hillman’s acoustic band with Herb Pedersen at the 1984 Telluride Bluegrass Festival, he made High Country Snows with some of his favorite bluegrass and country music pickers.

“I was going to the festival just to watch, and I walked into the condo complex to check in. And everybody was sitting there—someone’s flight had been cancelled, and they said, ‘You’re in the band!’

“We worked up some of the old bluegrass chestnuts, and we had such a good time doing it—I got to meet Doc Watson, an idol of mine. Then I realized, ‘Hey, wait a minute, I’ve got all of these songs lying around. Why don’t I put them in one place and do a bluegrass album?’ I wanted it to be a ‘nothing-serious’ album—purely musical. It’s all my songs, not old traditional songs. It’s commercial bluegrass, if there is such a thing. It’s not so radical compared to, say, what Joni Mitchell has been doing the last couple of years. It’s still gonna reach my audience. The more I make records, the more I want to just take one particular style of music per album and investigate it as a musician and songwriter. It’s a fine line to walk. I could get into trouble, but as long as I’m writing good songs that are my songs, I don’t think I’ll have a problem. And if I do, I’ll head right back into the middle again! I’m an artist, yes, but I do this for a living. I’d be crazy to get so far off the wall that I’d lose my audience.”

In a world he defined as “life in the fast lane,” Fogelberg described the music on High Country Snows as “life in the off-ramp.” The record became one of the best-selling bluegrass albums of all time.

“The record company didn’t appreciate it much, but for me it was a real musical milestone. The bluegrass thing reminded me again of how much fun music can be.

“It was really an outlaw move—after doing The Innocent Age, things had gotten huge. I was looking for a way to de-commercialize myself. Every once in a while, I have to jump off the track.”

Every one of Fogelberg’s first nine albums was certified gold or platinum. Reclusive by nature, he led a quiet life in Colorado’s San Juan Mountains. He let off steam playing anonymously in little Colorado bars in a good-time rock ‘n’ roll outfit called Frankie & the Aliens, formed with drummer Joe Vitale, his longtime cohort. He rehearsed them in a barn on his spread, then rented a bus and spent evenings driving to parts of Colorado and New Mexico—Vail, Aspen, Santa Fe, Durango—playing clubs on last-minute notice under the Frankie & the Aliens moniker. Having shaved off his famous beard, he went virtually unrecognized and reconnected with the fun-loving approach to music.

“Maybe people don’t know what the hell I’m doing,” he said at the time, “but I grew up playing blues songs, and this is like being in high school again; that is, it’s just like being in a garage band—I just live in a better neighborhood now! We’ve been going into towns and playing three sets a night, not shows. It’s been a ball, like giving a party for the locals wherever we’ve been.

“I actually started out playing electric music as a teenage in Illinois, in groups called the Clan and the Coachmen. The reason I switched to acoustic music is that I got sick of being in bands, dealing with personality hassles and all of that madness. It just happened to coincide with that time of my life when I was growing inward and starting to hear myself. I went inside and found a lot of stuff in there. Acoustic music was more interesting to me then—I listened to a lot of Gordon Lightfoot.

“By the time I got to college in ’69, I’d pretty much given up playing electric. I haven’t really been in a band since. I’ve made sure that I’m the boss in my bands—I get tired of democracies!

“This is so much fun for us to do. In the past, it’s either been a full rock ‘n’ roll production or a solo acoustic show. This is the best of both worlds. It’s human, quiet, folky. This format tends to break down the wall between the artist and the audience, real people playing real music. What a concept, huh?

“I’m never boring—but since there are a lot of critics who would disagree with that, let’s just say it’s never boring for me.”

Shuttling between his satisfying Colorado seclusion and the recording studios of Los Angeles, Fogelberg found his records took longer to make. So he built a home studio at his Mountain Bird Ranch.

“I’ve been so blessed and honored to work with and learn from great minds and musicians. People don’t understand—basically, it was a bunch of kids having fun. We should have been in school, we felt so guilty about it—‘You call this working?’ It’s like that Dire Straits song, “Money for nothing and your chicks for free.’

“It’s always been this wonderfully glorious, exciting, free process to the point now where I’m capable of engineering and mixing good recordings myself.”

The Wild Places, released in 1990, was the first album he self-produced and mostly tracked at his spread, which allowed him to be free from the time constraints of commercial studios. It included his soulful rendition of the Cascades’ 1963 hit, “Rhythm of the Rain.” The cover peaked at No.3 on the adult contemporary chart. In 1993, on River of Souls, Fogelberg recorded in part at his Mountain Bird Studios and played most of the instruments himself.

“I only had to go to Los Angeles once—God, is that great! It’s my home studio—I know the room real well now, I did a lot of the engineering myself.

“The album is more rhythmic and percussive than anything I’ve done, incorporating world music ideas. I saw that coming out of Bruce Cockburn and Johnny Clegg—I like their records quite a bit. I’m thinking of it as a musical travelogue. It has strings, horns, percussion—I’m making records that I can’t possibly perform live! I guess I’ll cross that bridge when I come to it.

“It’s got some fairly intimate love songs, but it’s balanced with a lot of politicization, songs about environmental and social issues.”

At his concerts, Fogelberg promoted reauthorization of the federal Endangered Species Act, which set out strict requirements for protection of animals and plants as well as essential habitat.

“We’re getting petitions signed—it’s critical that the ESA be strengthened,” he explained. “It isn’t in place forever, and there are some people who would have it taken out because it impedes their profit-making capabilities.

“But if it hadn’t been enacted in 1973, bald eagles wouldn’t exist today. I don’t know of a more convincing argument.”

In the early 2000s, Fogelberg’s devoted following wanted a solo acoustic tour.

“It’s funny how things in your life occur and you just go where it feels right,” he said. “It all grew out of a finger injury that I had back in ’96—I didn’t know if I’d ever perform again. Since then, my love of playing acoustic music has gone through the roof. I’ve reconnected with an appreciation of what it is to play and sing. It’s such a pure experience.”

Fogelberg knew his commercial appeal had evaporated.

“It’s got to be tough for younger musicians now, because the scope of what’s commercial is so narrow—radically different than in my day, when diversity was celebrated. It’s so conforming, stamped out of a press—the bands all look and sound the same, you can’t tell one rap artist from the next, and the little teen divas are hard to distinguish. But these are the biggest-selling things by far.

“But I and Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt have cultivated careers where we don’t rely on radio. We had our hits, but now it’s an educated audience—they chose music, music wasn’t chosen for them.”

Fogelberg’s long career was interrupted in mid 2004 by a diagnosis of advance prostate cancer. After battling for three years, he finally succumbed to the disease in December 2007.