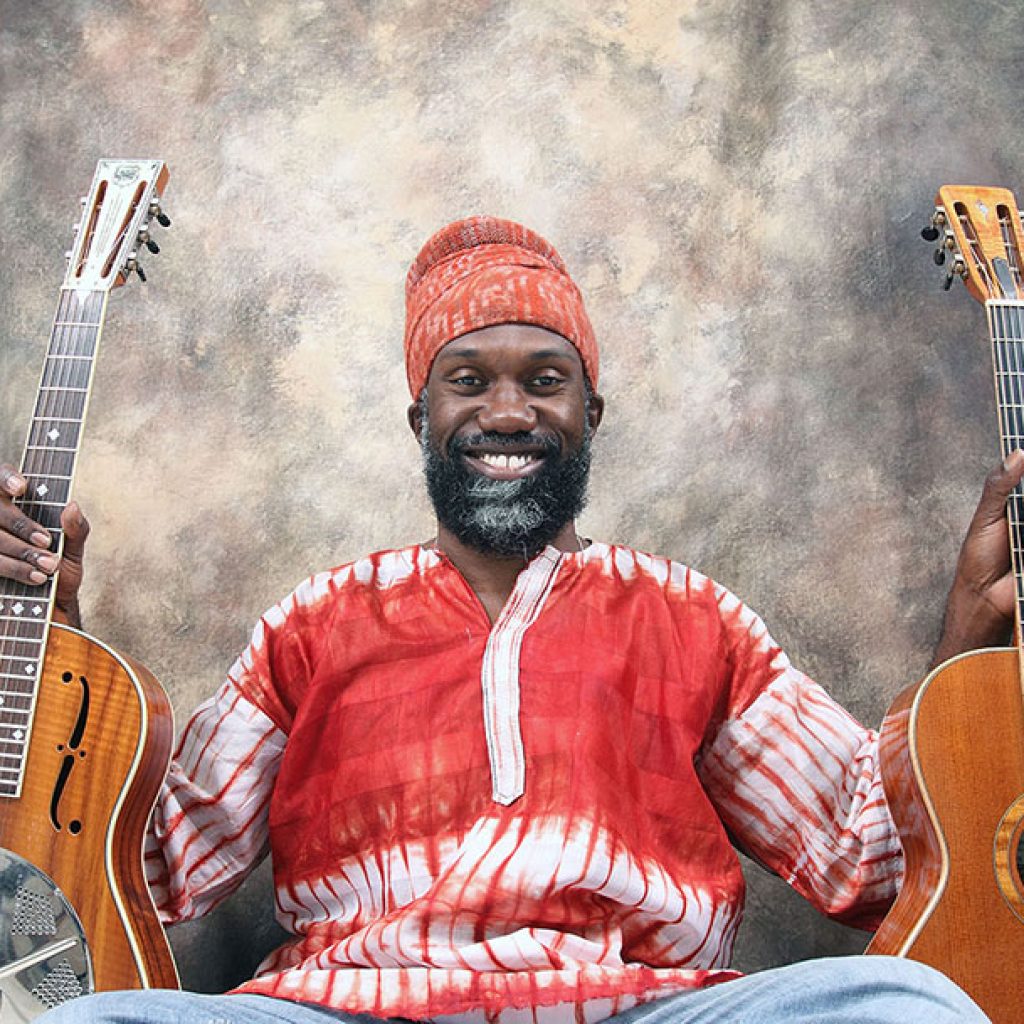

Corey Harris

Traditional acoustic Delta blues attracted a host of young performers in the 1990s and early 2000s, but Denver native Corey Harris was credited with revitalizing the breadth of black musical traditions.

“People are surprised that I come from Denver, but it doesn’t make sense to me,” Harris said. “The people I grew up around were all from the South. They moved to Denver for jobs, and wherever people move, they’re inclined to carry what they liked with them. My parents loved music, and I heard the blues at house parties and family celebrations from the time I was small. There’s an old saying that the roots of a tree cast no shadow. Everyone has roots, and they come out in their creations.”

Harris’s mother had wide-ranging musical tastes, and she encouraged him to listen to her collection of records. He gravitated toward the songs of bluesman Lightnin’ Hopkins. But his first instrument was the trumpet, which he played in the marching band at Isaac Newton Junior High.

“But I didn’t think the trumpet was as cool as the guitar,” Harris said. “So I switched.”

At Littleton’s Arapahoe High School, Harris played in a rock band, wrote songs and poetry and strummed guitar on the sidewalks of downtown Denver and Boulder.

“Littleton wasn’t known as a melting-pot,” Harris said. “I never felt like I belonged there, and a lot of the time I was made to feel that I didn’t belong there. But that’s often the truth of race relations in this country. And I had my family, thankfully.”

After graduating in 1987, a scholarship took Harris to Bates College in Maine, which led him to post-grad work in Africa, which brought him back to America—and the blues.

“I really came into my own playing on the streets of New Orleans, because I got to play with a wide variety of musicians, people who were better than me,” Harris said. “I learned what little music I know there.”

Harris’s second release, Fish Ain’t Bitin’, won the W.C. Handy Award in 1997 for Best Acoustic Blues Album. Since, his critically acclaimed releases have explored new sounds that incorporate reggae, ska, hip-hop, Latin and country styles. Comfortable in the pop-rock community, he has toured nationally with Dave Matthews Band and Natalie Merchant. In 1998, he was invited to participate in the Billy Bragg/Wilco collaboration Mermaid Avenue, which set a selection of unfinished Woody Guthrie songs to music.

“My obligation is to be fresh and to move forward with my material—which is what anyone who ever played music did,” Harris said. “When people like Son House and Charley Patton were playing music, it was really something new. They were singing in part of a blues tradition, but they put a different flip on it. After them, people such as B.B. King or T-Bone Walker played modern electric guitar in their day—and people didn’t like it at first. They got a lot of bad reviews.

“So whenever someone does something different, there’s always some resistance. But I think that’s a small price to pay compared to the cost of just sitting back and regurgitating things that have been done over and over again.”

In 2003, Harris served as the guide in the first episode of Martin Scorsese’s PBS series The Blues.

“But I think it would be a misrepresentation to say I am a bluesman,” Harris said. “That’s just a label that people put on me. I don’t really call myself anything but a musician.”