Warren Zevon spent a couple of years in the early 1970s touring as the Everly Brothers’ pianist/bandleader. After their breakup, he worked alternately with Phil and Don Everly—and sojourned to Aspen long enough to be appointed honorary coroner of Pitkin County, Colorado.

“My ex-wife grew up in Aspen, which is a sort of rarity, I presume,” Zevon explained. “So we ended up there. A friend of mine was running for councilman, and late one night in the Hotel Jerome bar, I said that if he won, I wanted to be appointed coroner. He said, ‘Well, it is an appointment.’ He won, and I was. I think of it like a perpetuity.”

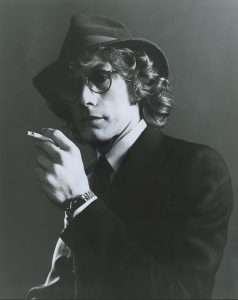

Singer-songwriter Zevon’s ironic tales of physical and psychological mayhem had earned him a cult following, and he was dubbed “the Sam Peckinpah of rock” after the director who opened the door for graphic violence in movies. In 1978, he’d had a Top 10 single with “Werewolves of London.” But his career was temporarily set back by alcoholism.

After a year in the studio and “in training,” Zevon’s 1980 release, Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School, represented something of a comeback for him, and he was eager to tour. First, he enlisted the aid of East Coast guitar ace David Landau. Then he met the group called Boulder (née Helix).

Boulder was seven players, most of them writers and five of them singers. The nucleus formed in Florida in 1972, and the other members, all veterans of bar bands throughout the U.S., joined in installments. The act was complete by 1976, when the members relocated to Colorado and acquired their name.

Boulder did college and club dates, but the members were wary of becoming a copy band and burning out on the road. They finally built their own rehearsal studio in a two-car garage in the vicinity of Denver.

“One of our roadies was a carpenter, and we went all out with hammers and nails and plasterboard,” drummer Marty Stinger recalled.

The band Boulder – Todd McKinney, Zeke Zirngiebel, Bob Harris, Stan Bush, Mithran Cabin, Marty Stinger

Boulder began recording material in Florida in January 1978 and did additional work at Caribou Ranch in Colorado. The band signed with Elektra/Asylum Records in November and moved to Los Angeles. The debut album, Boulder, included a harrowing and intelligent version of Zevon’s “Join Me in L.A.”

“We liked the theme of the song, and we were moving to L.A., where we’d never been before,” lead singer Bob Harris explained.

So Zevon took to the road, not with the L.A. session guys from his albums, but with the little-known Colorado group. The so-called audition consisted of a spirited version of “Johnny B. Goode.” Zevon’s somewhat sudden decision to record his new touring band in concert spoke volumes about the guy’s essential rock ’n’ roll attitude.

“The idea always appeals to me to find a self-contained band, or at least find musicians who are accustomed to playing with each other,” he said.

The difference was apparent on the live recording, Stand in the Fire, cut at the Roxy in Los Angeles. One of Zevon’s best albums, Rolling Stone called it “a portrait of the artist defiantly walking the line between emotional exorcism and mass entertainment.”

Throughout, Boulder anchored the star’s feisty roar with a tight, tenacious beat. Zevon struck up the band for the title track, a vigorous celebration of the rock ’n’ roll spirit driven by guitarist Zeke Zirngiebel: “Our lead guitar player’s scalding hot/And Zeke’s going at it, giving it everything he’s got,” he shouted proudly in a lusty, Elvis Presley-like baritone.

Zevon often performed shirtless on the summer tour, which was titled “The Dog Ate the Part We Didn’t Like,” a line borrowed from his friend, novelist Thomas McGuane.

“That was the culmination of a two-year physical fitness period in my life. I think I was celebrating the Chuck Norris-like physique of that era,” Zevon said.

“It was a real turning point for Warren because he had just gotten out of rehab and kicked the bottle,” Harris said. “He had this incredible amount of energy. All of a sudden, he knew where to put it, and he could turn it into being good.

“He went to some tailor in Beverly Hills and bought these $1,200 suits and was going to play in them—he’d been doing dancing and karate and was going to come across really classy. And about two weeks into the tour, he’d ripped the pants and the coats just leaping around on stage. So after that, he went out in blue jeans and t-shirt.

“Seeing him onstage every night, he was probably the most consistent performer I’ve ever seen. On the bus one night, he said, ‘Man, I had to realize that these people out here are my friends.’ It went from being good to phenomenal.”

But the success wasn’t enough to keep Boulder going.

“The producer from Elektra scammed the whole deal and screwed the band—which is not an uncommon situation, but we had our turn at it,” Harris said.

Meanwhile, Zevon continued his solo career. Time magazine’s reviewers gave “Song Title of the Year” to his rollicking “Things to Do in Denver When You’re Dead” from Mr. Bad Example, his 11th album. People magazine called it “a hoot.”

“Um, it had to be a two-syllable town—Indianapolis wouldn’t work,” Zevon explained. “It had to start with a ‘D.’ It had to have a Rattlesnake Cafe. Those were kind of the parameters. Everyone seemed to enjoy it the last time I played Colorado.”

In 2003, Zevon died of mesothelioma, a form of lung cancer, at age 56.