In July 1964, Peter, Paul & Mary played Red Rocks Amphitheatre and had to deal with a thrown beer can. The “beer can bomber” incident and general rowdiness were on everyone’s mind as the biggest group in the world—the Beatles—was set to appear in August. Many feared that the crowd conduct for the Beatles would not be acceptable. For that reason, a new ordinance was passed to ban alcoholic beverages, cans and bottles in the park. The security force was also increased—estimates ranged from 137 to 250 Denver policemen—and auxiliary recruits were briefed in “Beatle Invasion” strategies and assigned to “mop-top” duty.

Nevertheless, Denver, like the rest of the country, succumbed to Beatlemania in a tidal wave of sheer exuberance. The Beatles had appeared on The Ed Sullivan Show in February, and the first wave of the British Invasion, as it came to be called, was so swift that in the first week of April, the band held the top five positions on Billboard’s Hot 100 singles chart, which has never been accomplished by any other band or artist. The Beatles’ 32-day visit on their first American tour was the longest concert swing they ever shouldered. The sixth stop was a performance at Red Rocks.

For all of its seeming magnitude, the concert almost didn’t happen. The expense of bringing the band to Colorado was viewed as prohibitive, and the booking nearly fell through several times. The show was promoted by Verne Byers’ Lookout Mountain Attractions; Byers said he didn’t know the Beatles particularly well, but he was looking for someone to book in Denver, noting that they used their bowl-shaped haircuts as a “gimmick’’ to separate themselves from Peter & Gordon, the Beach Boys and similar acts that were touring that summer.

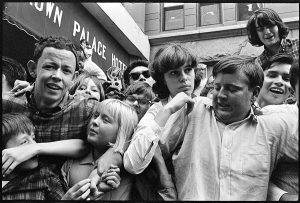

On the Wednesday morning of August 26, some six hours before the Beatles plane touched down, hundreds of kids bearing “I Love the Beatles” signs, Beatles hats and Beatles pins were already waiting at Stapleton Airport. By noon, nearly 10,000 had blanketed a fenced area on an adjoining boulevard. Huge numbers of sobbing and fainting teens mobbed the front entrance of the venerable Brown Palace Hotel on Broadway, where the group stayed before the show. Six girls and one harried policeman (who had been bitten on the wrist trying to hold back the hysterical mob) were taken to Denver General Hospital for treatment.

Nearly a thousand Beatlemaniacs also crowded the road leading to Red Rocks waiting for the gates to open at 3 p.m. Seating was general admission. Weather predictions called for rain, and emergency plans were made to transfer the show to the Denver Coliseum if necessary.

Later, the Beatles arrived at Red Rocks and were involved in a press conference back stage. Members of the Colorado Jaycees committee presented the four with official vests (called “boleros”) with the band members’ first names on them—John, Paul, George and Ringo.

Fans were polite for Jackie DeShannon, the Righteous Brothers, the Exciters and the Bill Black Combo, the opening acts on the bill. At 9:30 p.m., the audience erupted into 35 minutes of nonstop screams when the Beatles finally took the stage and opened with “Twist and Shout.” The audience was boisterous but polite—and whatever music might have been audible on the primitive sound system was drowned out by the teenagers’ piercing shrieks. The band, dressed in black suits, white shirts and skinny black ties, speedily performed its repertoire of hits, politely bowed to the audience, and left the stage without so much as an encore.

The altitude was the only factor that proved troublesome throughout the Beatles’ performance—halfway through the first song, they were gasping for breath. The members wound up using oxygen canisters that were placed nearby.

“We were all told it was high above sea water, altitude. We thought, ‘Well, so? What’s the difference?’ We got there, and we started finding it a little hard to breathe, because we weren’t used to it,” Paul McCartney said. “I remember singing ‘Long Tall Sally’ and thinking, ‘Hey, this is great, hyperventilation of the highest order! Well, Long Tall Sally, wheeze, wheeze…’ I was sweating, but I got through it. It was an interesting experience, physically. It was a lovely arena. It looked beautiful at night.’’

The Beatles were indeed pelted—with handfuls of jelly beans (reportedly their favorite candy), not beer cans. Police officers were stationed all across the front of the stage, and the wall held. Men on horseback, on foot and in jeeps along with mountain climbers cleared kids off the rocks who wanted a better view of the band, but many kids were determined to climb the rocks and sneak in.

Red Rocks was the only one of the initial dates on the Beatles’ 1964 tour that did not sell out—at least officially. Only 7,000 fans bought general admission tickets to see the show in the 9,000-plus capacity venue. Press accounts blamed the unsold tickets on the “out of the way” location, coupled with no public transportation for teens.

But photographs and news clips of the crowd showed a well over-capacity crowd and no empty seats. At $6.60, tickets were nearly $3 more than those for a recent performance by Igor Stravinsky, who was considered the world’s greatest living composer. Although the cost was consistent with prices across the country, many fans suffered from Fab Four sticker shock and plotted alternate ways to get into Red Rocks, which was still viewed as a mountain park rather than a musical venue. It was well-known in Denver high schools that there were hardly any gates, ticket takers and bouncers, and a few thousand enthusiasts managed to sneak into the event.

After the show, John, Paul, George and Ringo were whisked back to Suite 840 at the Brown Palace, and visited for a while with Joan Baez, who was in town for a gig at Red Rocks two nights later. The predicted rain finally arrived as the Beatles headed for the airport the following day. An estimated 3,500 people waited at Stapleton. Shortly after noon, the group left Denver for Cincinnati, never again to return as a band.

Reportedly, the $48,000 gate netted the city $2,000 in rent for Red Rocks, but as crowd control cost nearly $3,000, the city lost money on the Beatles.