Wayne Kramer, the co-founding guitarist of the seminal rock band MC5, whose social activism carried on throughout his lengthy solo career, died on February 2, 2024, after battling pancreatic cancer. He was 75.

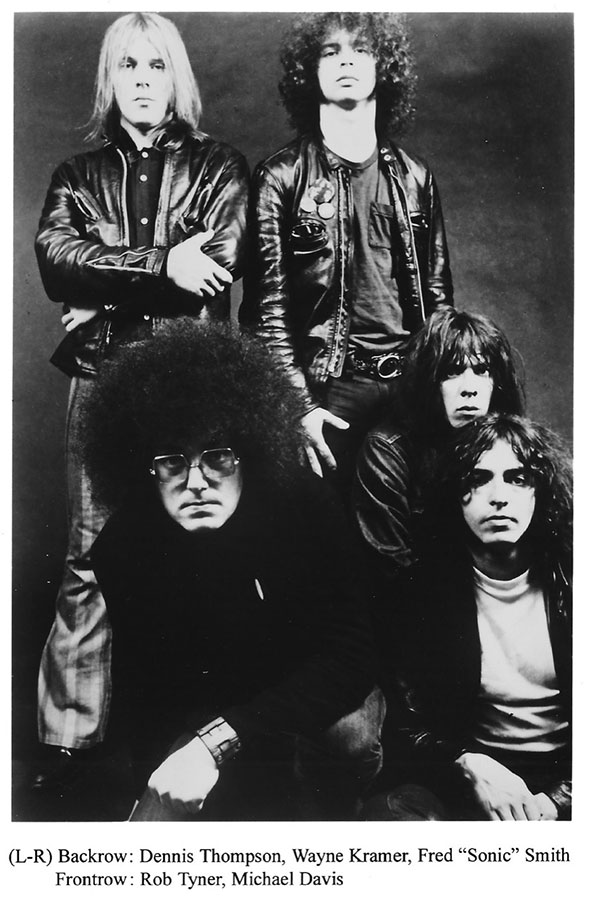

Kramer roused the rabble long ahead of his time, one of a handful of guitar players who changed the direction of rock music from his early days in the MC5. Though the storied group’s lifespan was brief, its influence was vast, providing the prototype for what would later divide into both the heavy-metal camp and the ’70s punk-rock revolution. Formed in Detroit when rage and uprising was tearing apart the city, the MC5 first rose to fame as the cultural spearhead of John Sinclair’s White Panther Party, whose radical politics cost the band its first record deal.

The MC5 battled its high-energy course through three albums—notably the incendiary 1969 debut Kick Out the Jams, whose expletive-inclusive title track put the band in hot water immediately, and Back in the USA, produced by critic Jon Landau before he shepherded Bruce Springsteen’s career. Kramer and his bandmates brought flash and fury to performances, from riots and street parties to legendary psychedelic venues such as Detroit’s Grande Ballroom and New York’s Fillmore East to some of the great open-air festivals of the time.

But the members found themselves ignored by the mainstream, slugging it out in the no-man’s-land between the commercial music industry and political extremism. The MC5 burned hot—and, by 1972, burned out. Kramer went downhill for years, including a high-profile stint in federal prison for dealing cocaine and a decades-long war with his personal demons.

The new millennium signaled a rebirth for Kramer as a happy and healthy solo artist, writing and producing projects and launching a label. In 2002, he promoted his loose ’n’ loud Adult World album with a club tour, hitting the Bluebird Theater in Denver.

“It was a long road,” he said. “I got off track for a while. I’m an alcoholic and a drug addict, and if I’m in the active part of that disease, it’s a full-time job. So a lot of those years, nothing got read and nothing got written and records didn’t get made. In the process of getting sober, I realized our time here is finite. If I’m going to make any mark, I’ve got a lot of work to do.”

Kramer still wanted to rock hard, but his lyrics touched on thoughtful, deliberate topics, among them a mid-century noir fiction writer (“Nelson Algren Stopped By,” featuring X-Mars-X, a Chicago avant-jazz group) and Fidel Castro (“Love, Fidel’). “I was intrigued with the idea that Fidel Castro was having an affair with this wife of a bourgeois doctor in Havana society,” he said. “I always loved Fidel—he’s one of my old revolutionary heroes. But to find out how human he was, too, that song had to be written. I write ’em because I have to.”

Kramer continued to rage against the machine. A dollar from every ticket sold on his tour went to the West Memphis Three Defense Fund, to aid three young men who were convicted in 1994 of murdering three 8-year-olds (supporters believed their conviction was in error and blamed “Satanic panic” due to the defendants’ alleged Satanic practices). Adult World was released on Kramer’s own MuscleTone records.

“You gotta get up in the morning and go to work, nothing but,” Kramer said. “And I’m loving it. We went to the (Small Business Administration), which I find ironic—here’s the same government that in the ’70s locked me up, and today is giving me a small business loan to start a record company. I feel like Don King—‘Only in America! Land of opportunity! Horatio Alger!’ They required us to go to business school, and I thought that was going to be a holy bore, and it was anything but—the instructors were high-end corporate consultants, very sharp. It was fantastic to learn why people really buy the things they buy, because I always thought everybody bought things according to price. But if that was true, we’d all eat at Taco Bell and drive Yugos.

“Ultimately, I would like to be the guy that could say yes. Maybe take these years that I’ve been in this game and apply them to good purpose, to help somebody else’s music find an audience.”

And that he did, spending the last two decades walking the talk. In addition to numerous musical endeavors, he served as an advocate for Jail Guitar Doors—a charity, named for the 1978 Clash song, that provides musical equipment to prisoners as a means of rehabilitation.