To students of rock music, Robert Hunter was known as an essential member of the Grateful Dead—an offstage presence who, primarily collaborating with guitarist Jerry Garcia, wrote the words for almost every Dead classic for nearly three decades, from “Dark Star” and “St. Stephen” through “Uncle John’s Band,” “Ripple,” “Truckin’” and “Stella Blue” to the Top 10 hit “Touch of Grey.”

“Any ol’ time Uncle Jer says, ‘Let’s write,’ I’m there with my pencil,” Hunter once vowed. The poetic, esoteric lyricist died on September 23, 2019. He was 78.

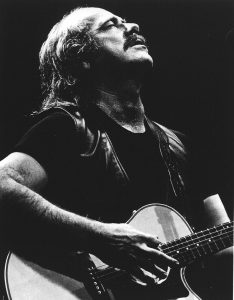

Although he was skilled on several instruments including guitar, mandolin and trumpet, Hunter never appeared on stage with the Grateful Dead. In the mid-’70s, he recorded albums similar to other Dead spinoffs and settled into solo acoustic gigs. In 1986, when the Dead hadn’t released a new record in nearly six years, Hunter pursued his own musical projects, and he embarked on a solo tour which brought him to Denver’s Rainbow Music Hall.

He had released two interesting albums—Flight of the Marie Helena was a unique recitation of an entire lyric over a musical background, while Rock Columbia was a more traditional rock ’n’ roll effort with full band arrangements. A reclusive sort who had shunned interviews in the past, Hunter had modified his attitude with his flurry of activity.

“When you’ve got a record and a tour, you forget about shy,” he laughed. “This is the first time I’ve gone out on stage without a set list, which is a liberation—I’m just trying to wing it, achieve more flexibility. I’ve got a large enough repertoire, so I’m checking out the audiences and seeing how we both feel on a given night.”

Hunter usually balanced his presentation with a good dose of tried-and-true Grateful Dead material. While he had hope of attracting people responsive to his own work, he ran the same risk of any Dead member who appeared outside of the band context—there were plenty of zealous Deadheads who simply wanted to breathe the air around their heroes.

“I know what the kids come for, and I’m not gonna short-change them,” Hunter mused. “It’s still a chance to meet people and get feedback on what I’ve been doing. The Grateful Dead has reached mythic proportions, become bigger than ever. It’s like being the Beatles or something out there, and it’s gratifying and a little frightening.”

He claimed to enjoy his own stint in the public eye. “I can’t really get very close to the mainstream in my work,” he conceded. “I’m just not capable of it, so I write whatever I write—and we’re all stuck with what comes out!”

Hunter released A Box of Rain, a solo album recorded live and live-in-studio along his 1990 solo tour. In 1993, his first spoken-word project, Sentinel, coincided with the publication of his collection of poems. He had been writing poetry almost exclusively.

Hunter’s work didn’t end with Garcia’s 1995 death. He re-emerged and visited the Fox Theatre in Boulder in 1997.

“It’s been about seven years since I’ve taken that guitar out,” Hunter said. “I swore up and down that I wasn’t going to do it. What happened? There was going to be a Rex Foundation benefit. The main performer had to cancel—Rex was left hanging. So Bob Weir jumped into the breach and said he would appear. And I thought, ‘Wow, man, what a mensch’—you know, if he could do it, by God, I could do it, too. And then it turned out that without knowing what Weir and I had offered, they had canceled this show. I found myself very disappointed. That was my first inkling that there was anything in me that wanted to perform. I worked hard for a month or so to convince myself this is truly what I wanted to do. I was fooling myself for lots of reasons—I was thinking, ‘I’m too old, my health is too bad.’ Well, I tell you, since deciding to do it, my health’s a lot better and I’m 10 years younger!”

Hunter’s Internet postings provided an information source for Deadheads. The genesis, he explained, was “Dog Moon,” a one-shot he wrote for DC Comics about a truck driver who, like the mythic Charon on the river Styx, transported the newly dead, and of his ordeal when he falls in love with one of his charges.

“They asked me if I’d do an America Online interview for it. I’d never been online before, so I said, ‘Yeah.’ I checked out the Dead site and it looked nice and snazzy but nothing was happening on it. And then I started cruising around other sites and I thought, ‘I could do this, it looks like fun.’ No sooner did the guys in the band find out that I was interested than they decided to make me Webmaster of Deadnet. I started cramming stuff on the site. After a while there wasn’t a whole lot more to say. Then I ran out of information on the reformation of the Grateful Dead after Jerry (died). But I started getting a lot of email. One thing led to another and next thing I knew, I was keeping a regular personal journal on there. It got to be a habit.”

One of Hunter’s most entertaining entries concerned his singing, which wasn’t exactly easy listening.

“I went to take vocal lessons,” he said. “I suddenly started thinking of myself as a baritone, and it really messed up what came out of me naturally. I decided to stop fancying myself a singer—and I consequently sing much better now.”

Hunter’s singing and songwriting outside the Dead was always an acquired taste—Deadheads seemed to either love it or hate it. But the real world was just a reflection in his compositions.

“I’m not concerned with sales,” he concluded. “I’m concerned with attitude.”