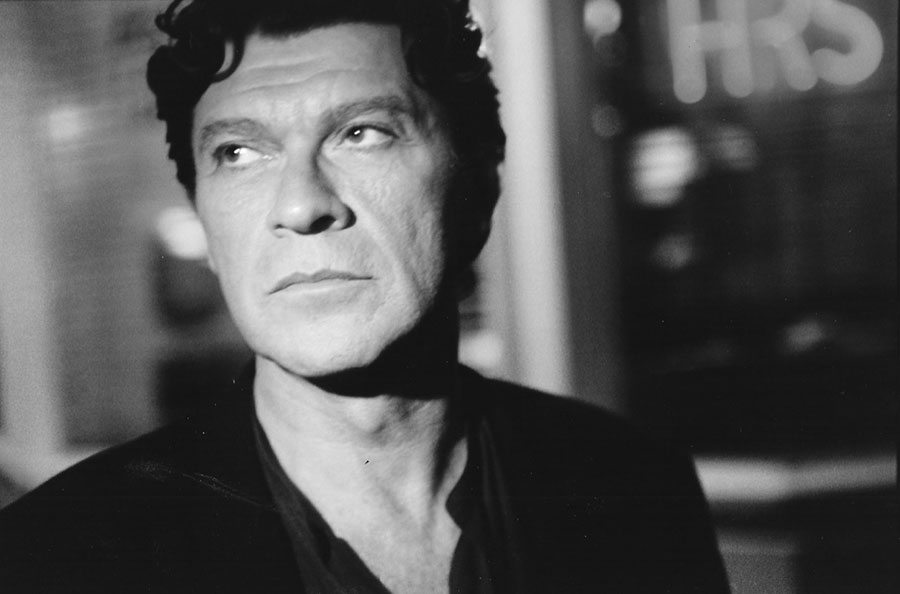

Robbie Robertson, the legendary guitarist and songwriter who led the Band into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994, died at age 80 on August 9, 2023.

Robertson had the magical skill to evoke places and people of early rural America with such Band classics as “The Weight” and “Up on Cripple Creek.”

“I have great gratitude and respect for the musical journey that got me here,” Robertson said over breakfast at Denver’s Brown Palace Hotel in 1998. “But I’m not real good at retracing my footsteps. One of the things that I’m thankful for is my curiosity factor. What makes me uncomfortable is not knowing what’s going on in music. I can’t hide under a rock. A lot of my friends from my generation decided a few years back that everything happening now is shit, and they just don’t listen or acknowledge it. Well, it isn’t for me.”

Robertson devoted the middle years of his career to the moody, atmospheric byways of popular music, making nods to his Native American roots. He had long hoped for a project to explore the music of indigenous Americans. He was half-Mohawk—his mother was raised on the Six Nations of the Grand River reserve in Canada. He formed a group called the Red Road Ensemble for The Native Americans, his soundtrack to a six-hour TBS documentary series by the same name in 1994.

“In the late ’60s, it was easier to find some ‘juice’ to take out of the air—there was incredible music coming from every crack in the woodwork,” he recalled. “Now I don’t have the same kind of juice. I’ve got to challenge myself. Rather than Paul Simon going to Brazil or Peter Gabriel going to Africa, what’s wrong with helping some people who live right here? It’s about time somebody made the effort to send out a taste to the world.

“I thought that the documentary was honorable, based on the fact that Native Americans would be speaking on their own behalf. It’s giving me the opportunity to make a record that’s been building in me ever since I was a little kid. We all try to find some events in our lives that give us inner satisfaction. This was it for me, a calling.”

Using Native Americans at all levels of production, Robertson teamed with a variety of talent. “For months, I listened to thousands of pieces of music—a lot of it is very local, you can only buy it on the reservation where it’s made. There are 400 nations. At the end, I thought, ‘Well, I’m the guy—I’m the foremost authority on Native American music in the whole world, thank you!’ Well, I’m not, but I felt that way.”

Robertson, who went into the project “thinking in traditional terms,” said he soon “discovered you can’t pretend it’s 100 years ago—you can only be inspired by that. We live here and we naturally think that Native American music is the cliched stuff we hear in movies, that the people live on the plains or in the woods. But I recorded in Manhattan—all of the people I worked with are very contemporary in what they do.”

When we spoke, more than two decades had passed since the Band had broken up. Robertson said he wasn’t the impediment to a reunion—it was Levon Helm, who accused Robertson in a book of taking sole credit for many collaboratively composed Band songs. In 1993, Helm, Rick Danko and Garth Hudson had put out Jericho, the first Band studio album since 1977.

“I have no problem with those people making a living—it’s with my blessing,” Robertson said. “I’m not interested in doing anything with the Band anymore—a lot of it has to do with Richard (Manuel, who committed suicide in 1986) not being there. But I’d hate to be carrying around that bitterness and anger. I didn’t even know it was there. If I was in Levon’s shoes, I’d be bitter, too. Things haven’t gone great for him, and he’s trying to blame me for it. But sour grapes just doesn’t play.”

On 1998’s Contact from the Underworld of Redboy, Robertson set out to plumb more of his past. “I returned to the reservation, and it triggered all these things that I felt I had to deal with. In Indian country, these traditions are all handed down to you like a gift. And you’re not supposed to hoard the gift, you’re supposed to pass it on. I had taken the gift and stored it in a trunk in the attic. And it didn’t feel good to me.

“And I didn’t know how to share it without it coming off wrong—a few years ago, I didn’t feel that there was a receptive place in people’s hearts. But the stars have moved into position or something. This is original roots music of North America that’s been so secretive, so sacred, so private. And to think that people would not be interested in it and embrace it is strange.”

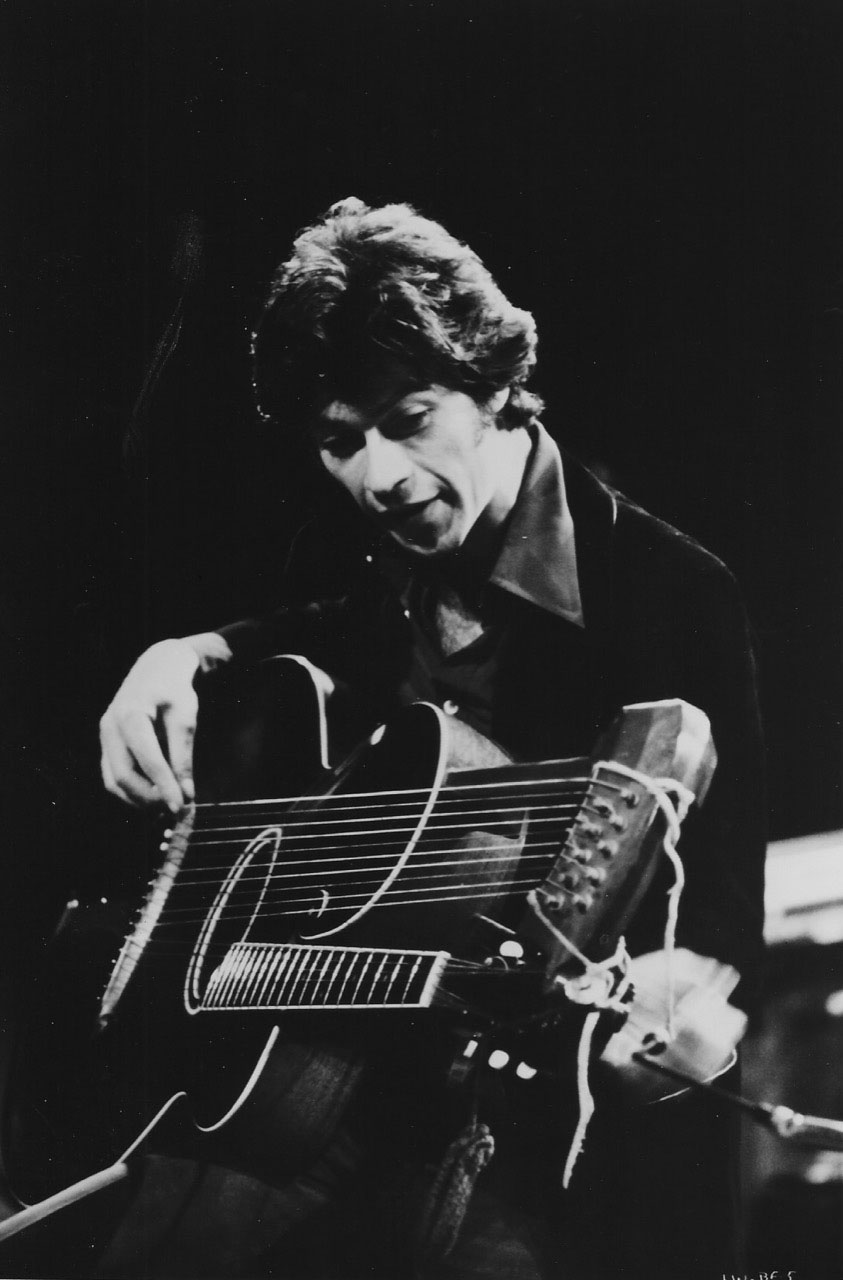

Robertson crafted a unique, charming album that owed very little to the Band’s enduring sound. The music blended traditional Indian tribal chants and rhythms with an up-to-the-minute electronic and ambient vibe interspersed with Robertson’s coarse guitar phrases and vocals. It was disquieting and richly textured.

“When Elvis Presley mixed country music and R&B, or when I first played with Bob Dylan and we were mixing folk and electric music—on paper, it didn’t look right. And not only that, people resented the change. But when those sparks do fly, it’s mystical. This was the experience of a lifetime. We didn’t have another record to compare it to. We knew that we were making a record that people had not heard before. That’s the good news. And the bad news, too, because it’s a little scary. You’re treading in unknown territory. So your barometer can only be, ‘Is this working for me emotionally, pushing buttons that send chills down my spine?’ That’s the reason we all like music.”

The rhythms came courtesy of London club underground deejay/mixer/producer Howie B (whose credits included U2, Bjork and Massive Attack) and Marius de Vries (the Romeo & Juliet soundtrack). A 53-year-old rock star keeping company with cool beat programmers, Robertson was also executive producer of the Phenomenon soundtrack—he put Eric Clapton and producer Babyface together with the song “Change the World,” which subsequently won Grammy Awards for Song of the Year and Record of the Year. He also rekindled a creative relationship with director Martin Scorsese, producing the soundtrack to his film Casino.

But Robertson hadn’t toured since “The Last Waltz,” the band’s final concert held in San Francisco on Thanksgiving of 1976. “Touring was like smoking,” Robertson said. “It was unhealthy for me. So I gave it up—so badly that I made a movie and a three-record disc about it. That lifestyle is tremendously beneficial financially, but I’m not interested in it. People go on the road and say, ‘Oh, I just love to feel the audience.’ Trust me—I did it for a long time and made that connection, but it becomes a business. And when it was no longer a growing process, I thought, ‘I want off this train.’ And then to come back and say, ‘Just kidding’?

“When it became clear to me that I needed to make this record, it wasn’t a decision that I weighted up in dollars and cents. It was, ‘What’s the best medicine for your soul?’ Nobody is telling me what to do. I don’t have to account for some pop formula. I’m fortunate enough to be in this free zone. I need to take advantage of that position and make whatever contribution I can.”