The crazy train reached its final destination when Ozzy Osbourne, the pioneering heavy metal singer and Black Sabbath frontman, died on July 22, 2025, at 76.

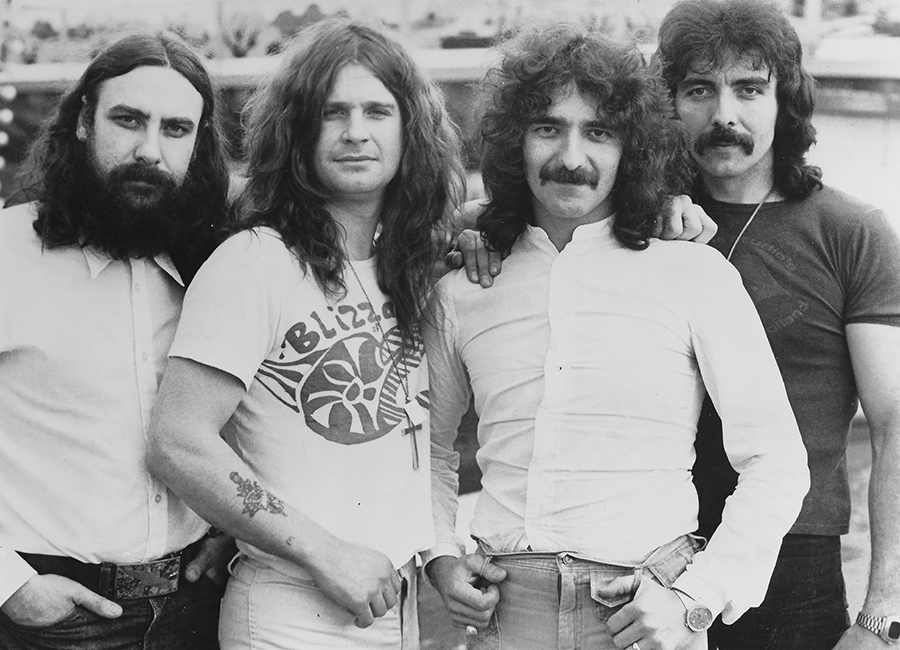

Black Sabbath came from a working-class section of Birmingham, England. Lead singer Ozzy Osbourne shrieked in a flat, ruptured wail. Because of an accident that cut the tips of his fingers, guitarist Tony Iommi couldn’t play comfortably unless his strings were slightly slack—so he tuned down his instrument, creating an ominous, menacingly loud wall of sound. Bassist Geezer Butler’s lyrics reveled in the occult and mental illness. Drummer Bill Ward never strayed from the same lumbering beat. But they were masters of the monster riff, and the classics “Paranoid” and “War Pigs” became their most enduring recordings.

Black Sabbath’s 1978 tour celebrated the band’s ten-year anniversary. Osbourne stated that the legendary British quartet’s longevity was starting to awe him. “Ten years, man,” he gasped prior to a concert at Denver’s McNichols Arena. “We’ve seen a lot of different styles and factions of music, and we’ve seen big bands come up and go down in the same year—and we’re still plodding along. I don’t know anything else. It keeps me thinking young, mixing with young people. I’m 30 years old, and I think, ‘Thirty! I should be in front of the fireplace, watching TV and eating popcorn and drinking beer every night.’ Nobody plays the records on the radio, so we’ve got to get the music out there somehow. If I sit at home, I just get fat and bored.”

The album Never Say Die pleased the group’s old fans and captured some new ones. “The audiences are ranging from 16 to 35 now,” Osborne noted. “I feel like Elvis Presley sometimes when I’m up there. But as long as the kids are there and want to hear us, then we’ll carry on as long as we possibly can. A lot of critics have put us down, but the main thing is that the kids still enjoy it. I don’t think there’s anything wrong with turning kids on to music. I’ll never forget the last time we played Denver because it was Halloween night, and it was one of the craziest gigs I’ve ever done in my life. There were so many freaks in the audience—the guy that won the competition was a headless man. I’d never done a Halloween gig in America before, but it should be like that every night.”

Osbourne gamely stuffed his Yogi Bear physique into a leotard to lead Black Sabbath’s concert ritual, but after a decade of drugs and alcohol leading to subpar performances and internal friction, he’d had his fill. He tried his own wings with Blizzard of Ozz. “When I first quit, to be honest, I thought, ‘What have I done now? I worked for 12 years to get this, and I just threw it out the window like a stupid fucker.’ But then I went out and got drunk for three of four weeks and got it together. The last few months with Sabbath, it was like dealing with a commitment, a corporation. We didn’t have to change. Now I’m doing it because I want to, not because it’s the only way to feed my family. I just figured that in the years I have left, I wanna have some fun.”

Osbourne’s first move was to recruit guitarist Randy Rhoads, an energetic youngster who provided the musical muscle for Blizzard of Ozz and the stomping “Crazy Train.” “I was frightened that people would forget me,” Osbourne admitted. “See, you could put four dummies up on a stage, call them Black Sabbath, and they’d fill a hall. Black Sabbath always had this weird cult following—we had black magic stuff thrown onstage perpetually. I’m definitely glad to be away from that—I’m a bit of a crazy fucker, but that’s all.”

Crazy wasn’t quite the word for Osbourne’s initial publicity stunt—supposedly he walked into his record company’s office and bit off the head of a dove. Messy but effective. “It makes me mad that people are blowing that out of proportion, because it isn’t true. It was totally staged—I walked in and threw a live dove in the air and then chomped on a fake one with blood capsules in my mouth. I had dealt with enough record companies to know you have to shake them up. And even if it was real, people eat chicken and steak—what’s the big deal about a dove?”

Osbourne became an icon through his best-selling solo albums, bizarre stage persona and rock star lifestyle. Multitudes of new headbangers revered him. He didn’t mind being famous. He just didn’t care for the way it had happened—as if biting the head off a live bat onstage was something to reconsider. During his 1982 “Diary of a Madman” tour, the expected backlash came to a head, as several conservative city officials successfully campaigned to have Osbourne’s concerts banned. He’d never expected the outrageous stunts to get out from under the shadow of Black Sabbath would take money out of his pocket.

“People want to hate me,” he groused before a concert at McNichols Arena. “I’m the guy your mother likes to hate. I’ve spent the last year trying to explain myself, and I’m not going to try anymore—people are going to prejudge me anyway, so what’s the use?” He made such nice-guy gestures as a donation to the ASPCA, another ploy to erode his I-snack-on-puppies image. Osbourne really wasn’t the ogre he appeared to be. He was extremely polite, although he had a distracted air about him, as if he was listening to voices no one else could hear. He had a domestic side—his wife Sharon gave birth to a daughter and the Osbournes were expecting again. Ozzy: “I’ve got to find out what’s causing it!”

Wanting to come off with his tongue planted firmly in his cheek, he envisioned himself as sort of a Vincent Price of the heavy metal set, and he had a ball doing what he did. “I don’t hang midgets onstage or throw meat into the audience anymore,” he said. “I’m tired of that hassle. I don’t want people to think I need all that lunacy to be good. Now it’s more basic so that the music plays a role, too.” Still, at the 1983 US Festival, he appeared onstage wearing a five-foot high headdress featuring skulls, bones and other paraphernalia, looking for all the world like a Native American in a Fellini movie.

In 1988, John Michael Osbourne marked his 40th birthday, while his musical alter ego, dubbed “the Prince of Darkness,” turned 21. “Ozzy Osbourne became a man this year—21 years in the music biz,” he crowed. “Now all I want is to be left alone to do my work.” Which was easier said than done. “I fail to understand why people still think I’m a devil worshiper after all this time. I try to ignore it and hope it goes away, but somebody always comes up with a weird interpretation of my songs. Now there’s a group accusing me of enticing my audience onstage to have baby sacrifices—it’s news to me. Stephen King writes horror books. John Carpenter makes horror movies. I sing some horror songs—and that’s all it is, a different angle on entertainment. If everybody wrote Pat Boone songs, it would be a pretty boring industry, wouldn’t it?”

His album No Rest for the Wicked kicked off with “Miracle Man,” which took a shot at the money-hungry, Bible-thumping capers of television evangelists. “I got a bit of a smile on my face when Jimmy Swaggart and Jim Bakker got caught with their groupies and their fun on the side,” Osbourne admitted. “It’s true hypocrisy, the likes of those people condemning me! They ought to sweep up their own backdoor before they start cleaning up after me. I’ve watched their programs over the past ten years where they’ve shown my album covers and said I’m Satan, that I should be banned. But they’re not doing any better themselves, are they?”

Osbourne had recently spent a second stint in an alcohol treatment program. “If anybody is sick and tired of being sick and tired, there’s more help in this country than anywhere else in the world, if you’re prepared to stick it out. Since I stopped drinking six cases of beer a day, I’ve dropped 18 pounds, I eat well, I have more energy and my attitude is good most of the time.”

In 1992, Osbourne retired from the touring circuit, rounding out his farewell “No More Tours” dates with a performance at McNichols Arena. Osbourne said that his immediate plans might involve his working with other musicians in a different format. “But my future will not involve a reunion with Black Sabbath. That would be like going out again with my first girlfriend.”

But Osbourne invited a reincarnated Black Sabbath—a lineup of founding members Tony Iommi and Geezer Butler and vocalist Ronnie James Do—to open for him at his final date in Southern California. Osbourne’s ex-bandmates accepted his offer, to the dismay of Dio—he flatly refused to front Black Sabbath on the bill. Osbourne didn’t feel like he was getting respect. “I find it very sad at this point in my career—after I’ve shared the stage with many great artists from Rod Stewart to Led Zeppelin to Metallica—that Ronnie James Dio doesn’t have enough respect for me to accept my invitation. I’m a shame that his ego has gotten in the way of a great night.”

Dio then became an ex-member of Black Sabbath. Fans figured a Black Sabbath reunion featuring Osbourne loomed, and Osbourne approached a reshuffled Black Sabbath about a two-week stadium tour, then a month, then a year, then a live album, then a studio album. “I was involved in trying to get it together on occasion, but there was a lot of weirdness and I couldn’t deal with all that shit. I got fucked when it was on one minute and off the next. I ended up with egg on my face. There’s still a lot of bickering. It’s not the band, it’s everybody’s fucking managers. So demanding! I could spend five days talking about it, but it’s so boring and petty, it’s a waste of fucking air. It’s too many chiefs and not enough Indians.”

By 1995, Osbourne needed a head start on his New Year’s resolution. “If a man can quit smoking, he can fly to the moon,” the jonesing singer said. “I’m trying, but I tell you, it’s one hour at a time—it’s 15 (minutes) to two, and I’m going, “14…13…” Osbourne’s resolve was stronger when it came to his return to music. It came as a surprise to many when he announced that his “No More Tears” tour would be his last, but you had to be nuts to think that his retirement would last very long. His latest tour, “Retirement Sucks,” kicked off at McNichols Arena on New Year’s Eve.

Ozzmosis, his first release in four years, was issued during a time when many pundits were claiming that hard rock had been replaced by alternative music. “All I can do is go into a studio and make a record. None of us ever say, ‘Okay, I’ve had a good run, let’s make a pile of shit for a change,’” Osbourne said. “There are so many bloody pigeonholes, brand names they keep giving it—grunge, metal, rap, soul, blues. The bottom line is, it’s all music. You’ve got a choice—you either like it or you don’t. I don’t know what key I’m singing in. I don’t know a guitar from a trumpet. I look at my arms, and if my hairs stand on end, it’s a good song.” Ozzmosis entered the charts at #4, the highest debut of his career.

“I just wanted to step aside for a while and look at what I’ve got. For years, I felt like a mouse on a wheel going round and round—it became routine. I was traveling around aimlessly buying houses that I was never living in, buying animals that never knew me, having children who thought I was a voice on the phone—basically living out of a suitcase for 25 years.” He had claimed his body could no longer handle the physical demands of a rigorous touring schedule, and his mind couldn’t handle the burden of being Ozzy Osbourne, heavy metal’s most famous radical—that former drunken drug addict who peed on the Alamo and tried to strangle his wife. “In my heart of hearts, I knew I wouldn’t retire forever,” he said. “But by announcing it, it was a final decision—everybody thought, ‘There’s no use asking Ozzy to come out to Bulgaria.’ I can honestly say that for one year in my life, I had no pressure. But in hindsight, I don’t know whether it was a good move. I had too much time on my hands. I thought, ‘What a stupid thing to do!’ So I’m back. And I ain’t gonna retire again.”

Osbourne’s new show was a career retrospective that included a few Black Sabbath songs. “I’m very proud of my time in Sabbath, the early days,” he said. “It was a long, long time ago. I don’t know where it came from—it was absolutely a gift. We never consciously sat down and thought, ‘Well, write the music now, and in 1996 people will look back on it as being an icon of its time.’ I’m as surprised as anybody. The original Sabbath started out playing jazz-blues—our influences were Ten Years After, Jethro Tull, Fleetwood Mac, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. But if you listen to how it developed, there’s no kind of blues—we never recorded a twelve-bar blues song, ever. The guys would come up with the heavy riffs, and I’d try to put a melodic vocal line over the top. If I couldn’t. I’d sing along with the riff, like ‘Iron Man.’ It was just innocence.”

But Osbourne had been the influential and popular godfather of heavy metal ever since. “To me, this new music is old music played by younger kids,” he said. “The vocal quality of a lot of the Seattle bands sounds like the Byrds, bands that were around in the ’60s. Nirvana was very Lennon-ish.”

By 1997, it was Marilyn Manson’s turn to be America’s favorite scapegoat, as several conservative city officials campaigned to ban Manson’s Ozzfest ’97 performances. “Let Marilyn have all that,” Osbourne said when his day-long extravaganza visited Denver’s Mile High Stadium. “I’m quite content right now, well rested.” Osbourne was apparently in another recovery phase regarding his drinking and debauchery.

At shows on the Ozzfest tour, after Osbourne concluded his full-length set, he was joined by Butler and Iommi onstage for a near-reunion of Black Sabbath. “We took our name and developed that ‘evil’ image as a way out of the gutter—we didn’t believe any of it. Sabbath was a musical irritant in that we didn’t conform to any set patterns, and it was the best education we could have. For a lot of kids, it’s became a fashionable thing to say they were influenced by Sabbath, but I can’t see it. For all I know it’s ‘Paranoid’ and ‘War Pigs,’ and there’s a lot more to Sabbath than that.

“But there hasn’t been a day that went by without somebody saying, ‘When are we going to be able to see the original Sabbath?’ I’d love for it to turn out great for the fans.”

The original members of Black Sabbath reunited and embarked on a six-week American tour, including a visit to McNichols Arena. Osbourne, who had turned 50, credited the reunion to his wife and manager, Sharon. “I told her, ‘You’re my manager, I’m your artist. I want to say to you: “Yes.” Now make it happen.’” The Reunion album, a 2-CD release, featured 16 live versions of Black Sabbath’s best-known songs, a few tunes that were loved by hardcore fans, plus two newly recorded studio tracks. The album debuted at No. 11 on the Billboard album chart. Were the band members thinking of all the money they could make? “Even if the tour and the album stiff, I’ll still be fine,” Osbourne said. “I’m really not a business-minded person.”

In 1999, Black Sabbath was nominated for the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, but didn’t get in. None of which bothered Osbourne a bit—he publicly called for the hall to remove Black Sabbath from the list of potential nominees (the group entered the pantheon in 2006). “I don’t care if the band is inducted. It’s an honor the business votes on, and Sabbath has never appealed to those people. But I would welcome it if it was voted by the fans. It would be interesting for my great-great-grandkids to be walking through the Hall and see my plaque and say, ‘What a nut case!’”