The band Rush announced that Neil Peart, one of the most virtuosic drummers in rock music history, died on January 7, 2020 at age 67, after battling brain cancer. Peart, a gracious and kind man, was also persistently cerebral, frequently dropping the names of authors and books in conversation. And fans were deeply saddened when he was devastated by tragedy in the late Nineties.

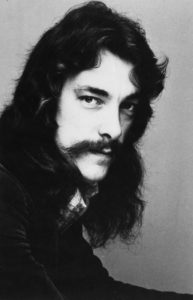

I first checked up on Peart in 1980, when Rush was knocking on the door of superstardom. The Permanent Waves album was soaring up the charts, and the band’s tour, which was selling out arenas across the country, made it to McNichols Arena in Denver—and Peart had recently shaved his trademark handlebar mustache.

Reaching the breakthrough stage was heady for a group that some felt would never gain an ounce of credibility or respect. Releasing their first album in 1974, the members of Rush had a number of strikes against them. They were a Canadian band trying to crack the US market. They were a power trio, considered an anachronism left over from the Sixties. They started out as just another hard rock band inspired by Led Zeppelin. And bassist Geddy Lee’s voice—an exaggerated hamster-on-helium shriek—definitely ranked as an acquired taste.

But Rush kept plugging away, evolving their heavy metal style to incorporate synthesizers and jazz timings to become one of rock music’s most musically articulate acts. Alex Lifeson developed into a disciplined, innovative guitarist. Lee tamed his banshee vocals.

Peart focused on tricky time signatures, and his extraordinarily precise drumming was a Rush trademark. He started writing lyrics based on compelling science-fiction oriented themes, a lyrical ability that always added an indispensible element to the Rush sound. He never underestimated the intelligence of the band’s predominantly young audience by offering standard “let’s boogie” sentiments. His interest in futuristic literature had resulted in such songs as “Tears” on Rush’s signature album 2112, which he based on Ayn Rand’s Anthem.

“It wasn’t thought to be the way to become popular before we became successful,” Peart explained of his intellectual approach, “but I don’t think people are stupid. That’s what it comes down to. When I write a song, it’s something that has captured my imagination. I merely give other people the same amount of credit. I’m full of ideas. If it’s a long one, we just go ahead and express it that way. We don’t have any external limitations, and that’s the key to our music.”

The band performed at McNichols Arena in 1986 in support of the platinum-selling Power Windows. Peart professed an understanding of the group’s reputation. “I have a comprehension of the music scene at a certain time, but never how we fit into it,” he noted. “No one can listen to or like all the music in the world, and I’m guilty of it, too. I hear of a group spoken of in a certain context, and until proven differently, I don’t take them seriously. So people have convenient labels and preconceptions—some still call us a heavy metal band, but anyone who knows our music and the changes we’ve been through realizes that’s absurd.”

The show transcended their past productions. “Touring isn’t glamorous or exciting, but playing live is what being a musician is about,” Peart concluded. “It comes down to the individual show. Everyone thinks, ‘Oh, it must be great playing New York or Los Angeles.’ People don’t understand that out of a tour, there are only a handful of shows that are memorable or magic, when everyone played well and the audience was terrific. Those things are just as likely to happen in Columbus, Ohio, or Fargo, North Dakota—or Denver. It’s just a magical confluence of variables that can affect a concert. The great reward doesn’t come from playing Madison Square Garden.”

Rush kept progressive rock alive and well, having become a top arena attraction by the time the band performed at Denver’s Fiddler’s Green Amphitheater in 1990. Presto was Rush’s seventeenth album, filled with varied tempos and ambitious arrangements. As usual, Peart’s literate lyrics were meditations on technology, media and the modern world. “I’m influenced by a lot of writing, but it’s difficult to quantify,” he said, “It’s a parallel of drumming—when you first start playing, there are certain people you tend to emulate, but the longer you go on playing, the broader your influences become. The same with lyrics. I’m drawing from a lot wider range. I’ve been studying prose writing over the last few years.”

When Rush returned to Fiddler’s Green in 1992 in support of the Roll the Bones album, Peart admitted that the band had been close to disbanding. “We each had different mindsets. But we’ve never thought too far ahead—we’ve always just established our next goal and then directed all of our energies toward that. Now we realize we can look to a long future. Everything we want to accomplish as individual musicians and writers, we can do within Rush.”

In 1994, after making music for more than 20 years with hardly a break, the band decided to take a vacation—and risk losing touch with fans. Peart worked on a Buddy Rich tribute, and by 1996, Rush returned more inspired than ever, hitting Fiddler’s Green behind Test for Echo, undoubtedly the band’s hardest-edged record since 1981’s Moving Pictures, which had yielded the hits “Tom Sawyer” and “Limelight.”

And then came an unplanned hiatus of unspeakable emotional turmoil. In 1997, Peart’s 19-year-old daughter, Selena, was killed in a car accident. Then, less than a year later, he lost his wife, Jackie, to cancer. Rush nearly called it quits, and to come to terms with his losses, Peart hopped on a motorcycle and hit the highway for more than two years. He later chronicled the experience in a memoir, Ghost Rider: Travels on the Healing Road. In 2000 he fell in love again and remarried, and the band finally entered a studio in Toronto to begin work on new material. Peart’s lyrics had turned to personal yearning and nature images. The band’s major North American tour behind Vapor Trails came to Fiddler’s Green in 2002, and Geddy Lee spoke of his bandmate.

“A lot of the songs are very directly related to his tragic experience and his recovery and his desperate attempt to put some philosophical attachment to what had happened in his life,” Lee said. “But in some cases they were expressed in a very first-person way that was so intimate at times I couldn’t sing them. As his interpreter, in a sense, I had to have them shifted more to the third-person and a slightly more objective outlook on the same thing. We did a lot of back and forth until we struck a balance. He’s in a very good frame of mind right now. With every passing day, time is doing its work in healing him, in small ways, sometimes, but nonetheless. The incidents of his life are not ones that you really get over, but you just learn to live comfortably with them. Once we got into making the record, he found that renewed enthusiasm for writing and making music again. I think he considers himself to be fortunate that he’s gone through the worst thing that a man can go through and still found that there’s life after that.”

Rush was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2013, and Peart announced his retirement two years later. Few people knew he was fighting a debilitating disease in recent years. One of the last lyrics he penned was “The Garden” from the 2012 album Clockwork Angels: “The treasure of a life is a measure of love and respect/The way you live, the gifts that you give/In the fullness of time/It’s the only return that you expect.”

Remember his music, and he will live that life forever.