Mike Peters, the frontman and songwriter of the Alarm, died on April 28, 2025, at age 66 after a long battle with blood cancer.

The Alarm debuted on the international recording scene circa 1982, and the quartet had to live with a convenient tag—many people considered the group a U2 knockoff. That comparison was based in some fact—certainly the two acts shared a penchant for writing anthemic calls-to-arms and taking declarative lyrical stances. The Alarm’s affiliation with U2 went back to the Welsh band’s first British tour, when the two groups played several showcase dates together. “We had to break it off,” Peters explained over the phone from his home in Rhyl, Wales. “They’ve been very supportive and we’re fast friends, but we didn’t want to get tagged as ‘U2’s opening act.’”

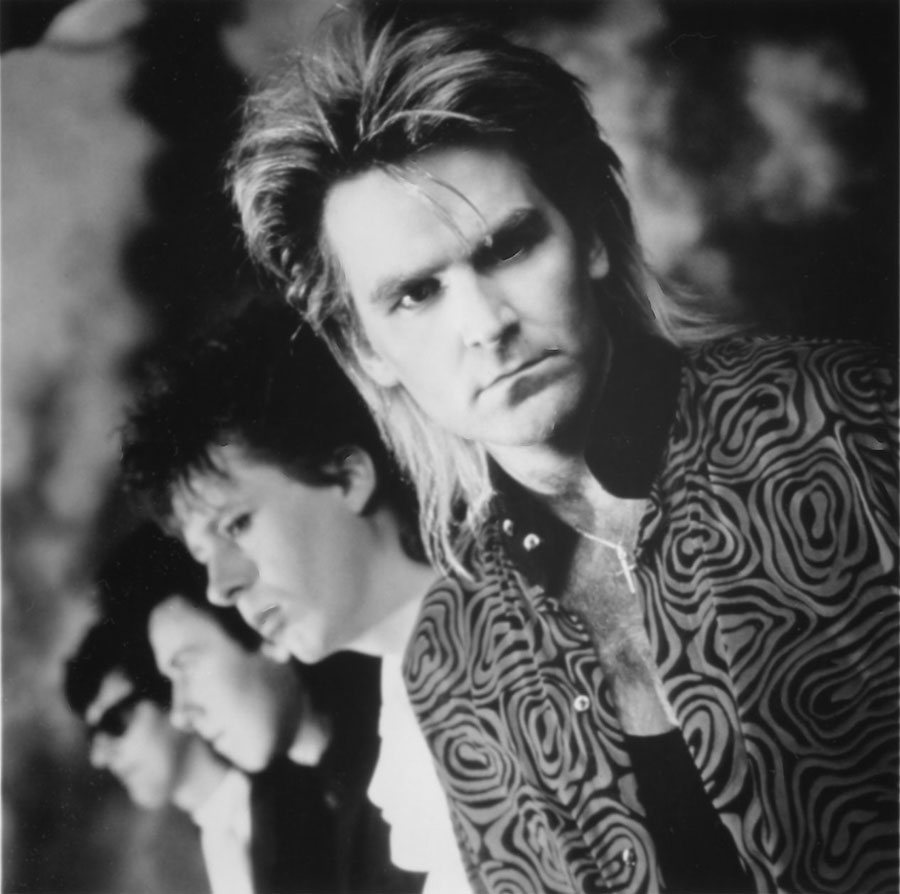

The Alarm managed to attract attention on their own. The members—singer Peters, guitarist Dave Sharp, bassist Eddie MacDonald and drummer Nigel Twist—grew up together in northern Wales, and by the time they reached their teens they were ready to command the regional music scene. They took their name from the first song they wrote, “Alarm Alarm,” and began playing to scrape up money for some time in a recording studio.

“We bought acoustic guitars, and it’s turned into our trademark sound,” Peters noted. “We tried electric and it didn’t work, anyway. With acoustic guitars, we’ve been able to rehearse in a flat, carry our own equipment and generally keep things within our own circle.”

The sound of “Sixty Eight Guns” was also reminiscent of the Clash. The band’s acoustic style was unveiled to audiences on the first American tour. “We picked up a loyal following of Americans that were staying in London,” Peters enthused. “They’ve gone back happy and spread the word. So I think we’ll do well—we like a lot of American music, like Springsteen and Dylan. We’re a live group, not like Culture Club or Human League, groups that don’t tour a lot. We want to play every night of the week, every week of the year.”

The Alarm gained a reputation as a searing, passionate live band that communicated better in concert than on record. With the 1985 album Strength, the members phased out several career-launching traits as they took on a new direction. Instead of the rebel-rousing anthems that had comprised the group’s repertoire, Peters contributed some very personal material based on his own experiences. The quartet had nothing to do when a studio session was postponed the previous year, and Peters called it “some of the most valuable time we’ve spent since the group started. It was the first time we were able to step out of the spotlight and have a good long look at the band, to see what we’ve achieved. We decided to see how good the ten new songs were—we went out and did our biggest tour in Britain. I did a lot of talking to the audience, telling them to write us what they thought. We got tremendous response, but some people said, ‘Mike, we don’t want you to write “we” all the time. We all know what “we” think. We come to the concerts to know what you think.’”

Some self-interrogation followed and gave Peters the inspiration for the song “Spirit of 76,” a lengthy street symphony. “It’s about me getting into music for the first time,” he explained before a performance at the Rainbow Music Hall in Denver. “Ten miles across the water from Rhyl is Liverpool, and me and my friends were attracted there to find entertainment. We would go down in the basement of this club where the Beatles had started off, and it was there that we heard the Buzzcocks and the Jam, all that sort of thing in ’76. It made us feel like the world was our oyster. I just wanted to step off for a few years and see what I could do, go see the world, experiment—’I’ll give it a few years, and if nothing happens, I’ll go back to being a computer operator and the straight line.’

“I wrote that song about what happened not just to me, but my friends who were part of that audience—how people coped with that inspiration in the last ten years. John and Suzie (mentioned in the first part of the song) were my best friends from school—they felt the same way as me, but we went our separate ways to achieve things. I met them a year ago and saw two very disillusioned people—their lives had been battered and kicked into the ground. I felt really sad, because I think when people become downhearted, that’s when the crime and drugs get ahold of them. Our music is about fighting those things, fighting the blackness in your heart. ‘Spirit of ’76’ is a similar thing to the American way of life, establishing your independence as a nation. That’s what we were trying to do in 1976, establish our own independence.”

Another modification concerned the Alarm’s appearance—the group abandoned the oversized hairdos and Peters’ shock of long blond hair that had become trademarks. “Looking the way the band did established our identity when we started,” Peters insisted. “But I had to cut it in Detroit—it was just getting so long, I couldn’t handle it. It was time, though. Now I think we’re known for the content of our music, not the style of our hair or the shape of our guitars.”

Developing an exuberant, stirring approach to live performances, the Alarm nurtured an impressive communion with fans.

“That community atmosphere in the concerts doesn’t come easy to a lot of bands,” Peters mused prior to another Rainbow gig. “It’s not something that you get overnight—we’ve always made the effort to communicate with our audience verbally as well as lyrically, by meeting them after the shows. And one thing the audience knows about the Alarm, we do personalize the show wherever we are—our set is different every night. A lot of people don’t realize that the Alarm has been playing live for a decade now. It’s only been in the last four years that we’ve made records. Live, we’ve played thousands of gigs whereas we’ve only made three albums. It’s always been our goal as a band to achieve on record what we can do in a live situation.”

Peters cited “Rain in the Summertime,” built on a cascading guitar arrangement, as an allegorical tune symbolizing a “dry stage” the group went through. “We had been uprooted with our last album, thrown around the world for the first time,” he noted. “When we got back, we realized we’d all changed quite a lot since we’d known each other, since we were 15. So we grew close again and solidified our relationship, and made a record for ourselves without the constraint of a domineering producer. That song was very free-form, only loose ideas when we went in the studio to put it down. People are actually hearing the moment of creation, which we’ve never had on record before.”