Meat Loaf—real name Marvin Lee Aday, “but nobody ever calls me that”—died on January 20, 2022. He was 74. His Bat out of Hell albums were perhaps the most grandiose, bombastic, melodramatic—and multi-platinum and Grammy-winning—series of rock pseudo-operas in history.

In 1978, the beefy singer broke onto the rock scene with Bat Out of Hell, which was shopped around for years before it was finally released, and it took months to gain traction. But fueled by three hit singles, it roared up the charts, going on to sell 30 million copies worldwide.

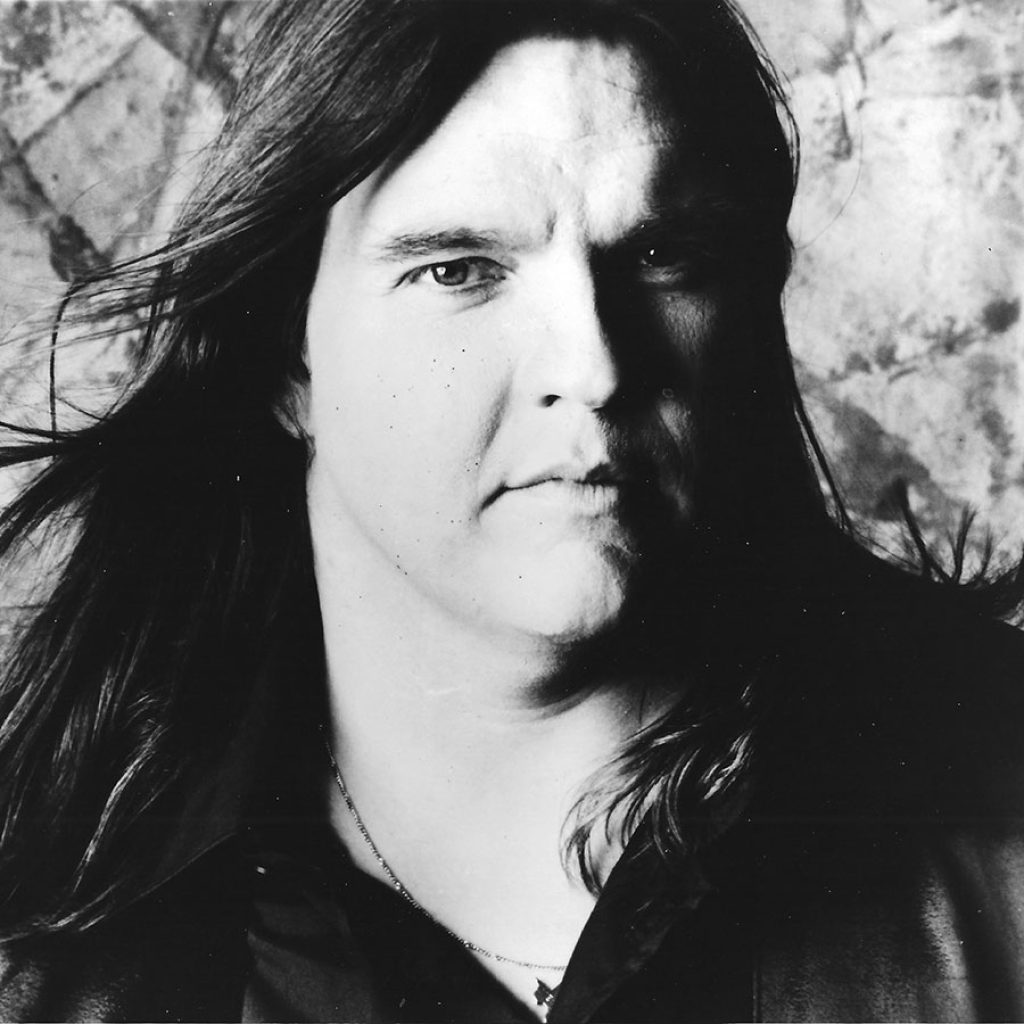

Meat Loaf presented an unforgettable image to the public—at a time when rock musicians took pains to appear as traditionally waif-like as possible, he resembled a grocer who was eating up all the profits. And from inside his man-mountain stature came a voice of near-operatic proportions. It served as the messenger for writer Jim Steinman’s over-the-top mini-dramas, which treated teen angst in terms of Wagnerian excess. Todd Rundgren’s dense production of “Paradise by the Dashboard Light,” “Two Out of Three Ain’t Bad” and “You Took the Words Right Out of My Mouth” made Phil Spector’s “wall of sound” look like a white picket fence.

But that powerful, passionate voice failed Meat Loaf as suddenly as it had catapulted him to stardom. At the height of Bat Out of Hell’s popularity, the pressures of that success stripped him of his singing powers and left him in a career limbo. He was just finding his way out of it when he performed at Denver’s Rainbow Music Hall in 1983 in support of his third album, Midnight at the Lost and Found.

“Hey, I’ve only been to Colorado once before,” he recalled. “I was up at Caribou, the recording studio up in the mountains, and we were having a big dinner with a lot of people. Record company executives, managers—people were flying in from everywhere. The dinner was scheduled for 11 at night. But the air was so thin that I passed out at 8:30 and slept through the whole thing! So if I’m not onstage when I play Denver, everyone will know the reason—Meat’s asleep!”

Meat Loaf had a well-developed sense of humor about himself, and he had no qualms about dissecting the ups-and-down of his career. “The problems with my voice were all stress-related,” he admitted. “I just let myself go wacko from and during the success of Bat Out of Hell—it was psychosomatic. I spent over two years just doing nothing but wondering where my voice had gone. I finally decided to work, so I starred in the movie Roadie. My psychiatrist told me to do it just to be doing anything.”

Meat Loaf had plenty of prior acting experience—he had performed in a touring company of Hair and made a memorable appearance as Eddie in the classic cult film The Rocky Horror Picture Show. “And more work in film will come,” he predicted. “It only takes 10 weeks when you want to do it. Right now, I just want to tour and record. Tom Dowd (producer of Midnight at the Lost and Found) was the one who helped me get my confidence back. He just said, ‘Ah, there ain’t nothing wrong with you, kid. They’re just songs—get in there and sing ’em!’”

Before meeting up with Dowd, Meat Loaf had made a previous attempt at recording a follow-up to Bat Out of Hell. Steinman grew tired of waiting for Meat Loaf’s voice rehabilitation to finish and used the material intended for a second Bat album as his first solo album, Bad for Good. Meat Loaf gathered other Steinman songs for his eventual release, 1981’s Dead Ringer.

(Steinman: “When Meat came off the road, his voice was shot to hell. There was a little physical damage, but a lot of it was mental—he couldn’t deal with having to follow such an amazingly successful record. He went to doctors and specialists everywhere, and no one could find anything wrong. Meat finally found this doctor in California who did his voice some good. The guy is either crazy or a genius, but he took Meat and induced a violent allergic reaction in him—Meat’s allergic to a thousand things, but he used cat hair. Then he injected Meat’s urine back into his bloodstream. Then he covered him with mats and beat the living hell out of him. It was pretty strange walking into therapy and seeing Meat all swollen and screaming under those mats while this guy pounded on him. He’d stop yelling just long enough to look up and say, ‘Isn’t this weird?’ But I swear to God, it was the only treatment with any results.”)

“Dead Ringer for Love” from Dead Ringer was a smash hit in the UK—nearly everywhere except America, a fact that still irked Meat Loaf.

“Radio had closed minds just because it was a duet with Cher,” he fumed. “It was a hit song, as was proven elsewhere, and when we do it live, the crowds get off on it even though they don’t really know the song. In other countries, it didn’t make a difference that Cher had played Las Vegas and Atlantic City, but over here the radio people said, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, but we don’t play her kind of music.’”

Midnight at the Lost and Found was his first album not to feature the songwriting prowess of Steinman, which had forced Meat Loaf into taking on that responsibility. “I don’t like songwriting, but I’m getting better at it. I learned a few tricks from the best guy in the biz—Steinman. I’ll be working with him again, as soon as he gets away from his fucking manager who’s suing me for all my money.”

Steinman was currently hotter than ever, with two hits on the charts that he had written and produced for Bonnie Tyler (“Total Eclipse of the Heart”) and Air Supply (“Making Love Out of Nothing at All”). A Meat Loaf-Steinman reunion was worth waiting for, but by that time Meat Loaf knew that things never came as easy as they should.

“I’m serious—I’m poor,” he laughed. “I mean, I’m being forced to eat Twinkies and tuna fish sandwiches, and to walk from gig to gig…”

In 1993, Meat Loaf once again partnered with Steinman and recaptured the magic. Bat Out of Hell II: Back into Hell continued the original’s story and duplicated its thunderous sonics, propelling it and the single “I’d Do Anything for Love (But I Won’t Do That)” to No. 1. He released another single from the smash album, “Objects in the Rear View Mirror May Appear Closer Than They Are.” It was collaborator Steinman’s metaphor for the pain of coming to terms with the past and embracing the present.

“I spent three days in a rehearsal studio with Jimmy and his notebook, forcing that song out. He had some lyrics floating around and that line about, ‘If life is just a highway and a soul is just a car, then objects in the rearview mirror may appear closer than they are.’ I sat there and made him put it together. He came with the arrangement for ‘I’d Do Anything for Love’ all written, but ‘Objects’ was the tough one. It’s very difficult for him to write a song, really hard. He can turn out plays or scripts, but he hates writing songs. I don’t know if he gets possessed or what. He loves it when he’s done, but the actual process—he’d just as soon have open-heart surgery with no anesthesia. So there are very few songs of his that you don’t know about—they’ve all been placed somewhere.”

Meat Loaf sold out a show at Denver’s Auditorium Theatre in March 1994, and he returned to town that August to perform at Fiddler’s Green Amphitheater. He was taking the impending Major League Baseball strike hard—he was a New York Yankees fan and a fantasy league geek. He had sung the national anthem at the All-Star Game that season.

“I have the Colorado Rockies Opening Day program in my collection,” he enthused. “But I’m an American League guy. I like the realignment, I think it’s good for baseball. The playoffs bring people to the ballpark, they like to see their teams competing. So I’m devasted (by the strike). All along, the inside information I got from owners and players was that there isn’t going to be a World Series this year.”

Meat Loaf performed at Denver’s Universal Lending Pavilion in 2003 to promote Couldn’t Have Said It Better, a stylistic cloning of the Bat series. The plus-size singer worked with a roster of eclectic songwriters, and the compositions sounded exactly like Steinman’s work, particularly the title track and the tear-jerking “Did I Say That?” Meat Loaf was calling it his best collaborative effort since the original Bat Out of Hell, but he planned to devote himself to his rekindled acting career (in 1999, he appeared as Bob Paulson in Fight Club).

“I was on tour from ’83 to ’91, then ’93 to ’97. I can’t tour like that anymore—I have to stop. I was planning to make this my last album as well.”

But his rock ’n’ roll retirement plans looked premature. “I got an e-mail from Steinman saying ‘We gotta do Bat III,” he said. “The problem was, my ex-manager was Steinman’s manager. For a while, he’d try to keep Jim busy doing other things. Last year, Jim finally got rid of him.”

Work began on the final installment of Bat Out of Hell. Meat Loaf knew no other singer could pull off the humor and theatricality of Steinman’s grandly cinematic songs.

“I don’t want to sound like George Lucas, but Jim always said he thought of Bat in terms of a trilogy. But it’s a slo-o-o-w process.”

Released in 2006, Bat Out of Hell III: The Monster Is Loose included some songs but no production involvement by Steinman, who died in April 2021. Meat Loaf issued his last studio album, Braver Than We Are, in 2016.