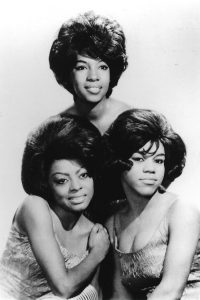

Mary Wilson, a founding member of the Supremes, died at the age of 76 on February 8, 2021. Pop music fans recognize Wilson as one-third of the iconic singing trio that epitomized the Motown sound with a remarkable string of mid-’60s hits—12 No. 1 singles including “Where Did Our Love Go,” “Baby Love” and “Stop! In the Name of Love.” Wilson was the only member to stay with the Supremes from the beginning to their dissolution in 1977, seven years after Diana Ross departed.

In 1986, Wilson told her story—and, hence, her account of Ross’ rise to international stardom—in Dreamgirl: My Life as a Supreme, the first trenchant tome by a member of the Motown family. She had toured the world with her own band, performing in countries in the Far and Middle East, but in America she had made only occasional appearances in Las Vegas and Atlantic City. She explained her literary motivations in Denver on a book tour.

“The play Dreamgirls, the Motown 25th anniversary television special, the resurgence of that classic rock ’n’ roll—those things did let me know that my timing was right,” the attractive singer said. “But none of them had anything to do with my writing the book. I was one of the players who experienced a true phenomenon of the music business, and I’ve always wanted to share the story. I was into something heavy when the Supremes became real popular—people from all walks of life all over the world would tell us how we had touched them in some way.

“I just had to find the right time to write it, to be objective. I had to give other people time to grow up, too, so things wouldn’t hurt them—because sometimes the truth hurts.”

Wilson was alluding to her candor regarding Diane Ross, a skinny black girl from the Detroit projects who eventually became Diana Ross, superstar. Wilson told all—how she and Florence Ballard (the other third of the Supremes, who died at 32 after a long bout with alcoholism) shared the lead singing with Ross until Motown president Berry Gordy gave Ross all the leads in 1963; how Ross devised attention-grabbing stunts at their expense on her way to the top; how Ross manipulated top billing through her close relationship with Gordy.

Predictably, scandal magazines went wild over Wilson’s disclosures, and every negative word in the book was reprinted in one tabloid’s excerpts. But there had been no response from Gordy or Ross. “I was always the quiet rebel in the group, and they really don’t know how to take me being so outspoken,” Wilson said with a grin. “But they’ll eventually come out with something to say. When Diane writes her book, you’ll be seeing the rest of us through her eyes, and that’s valid, too.”

To her credit, Wilson’s tone in the book was regret rather than it-should-have-been-me vitriol. She offered other elements that appealed to readers of celebrity bio fare—she detailed her affair with Tom Jones, and she stuck up for the tragic figure of Ballard. And she divulged some youthful, innocent anecdotes about Motown, the musical hit factory.

“The artists made Motown,” she said. “The public has been led to believe that we were little puppets, but we share credit. Stevie Wonder, Marvin Gaye, the Supremes—no one went out and found us. We went to Motown and wanted to be signed.”

But for all Wilson’s soul-baring, Dreamgirl never resolved her ultimate feelings toward Gordy and Motown—something the 2006 movie, Dreamgirls, reinforced. “No one person knows it all about Motown. The artists didn’t get to see the business end, but rumors were flying all over the place. But I couldn’t write about things like Mafia connections unless I had proof.

“People want me to be bitter. I wrote the truth, but I am not bitter. Yes, I will say until the day I die that they were not fair to young girls who came there—we weren’t treated fairly regarding record royalties. But I also know we were glad to be there. They could have given us nothing at that point and we would have been happy. Not many companies could have put the Supremes where we were.”