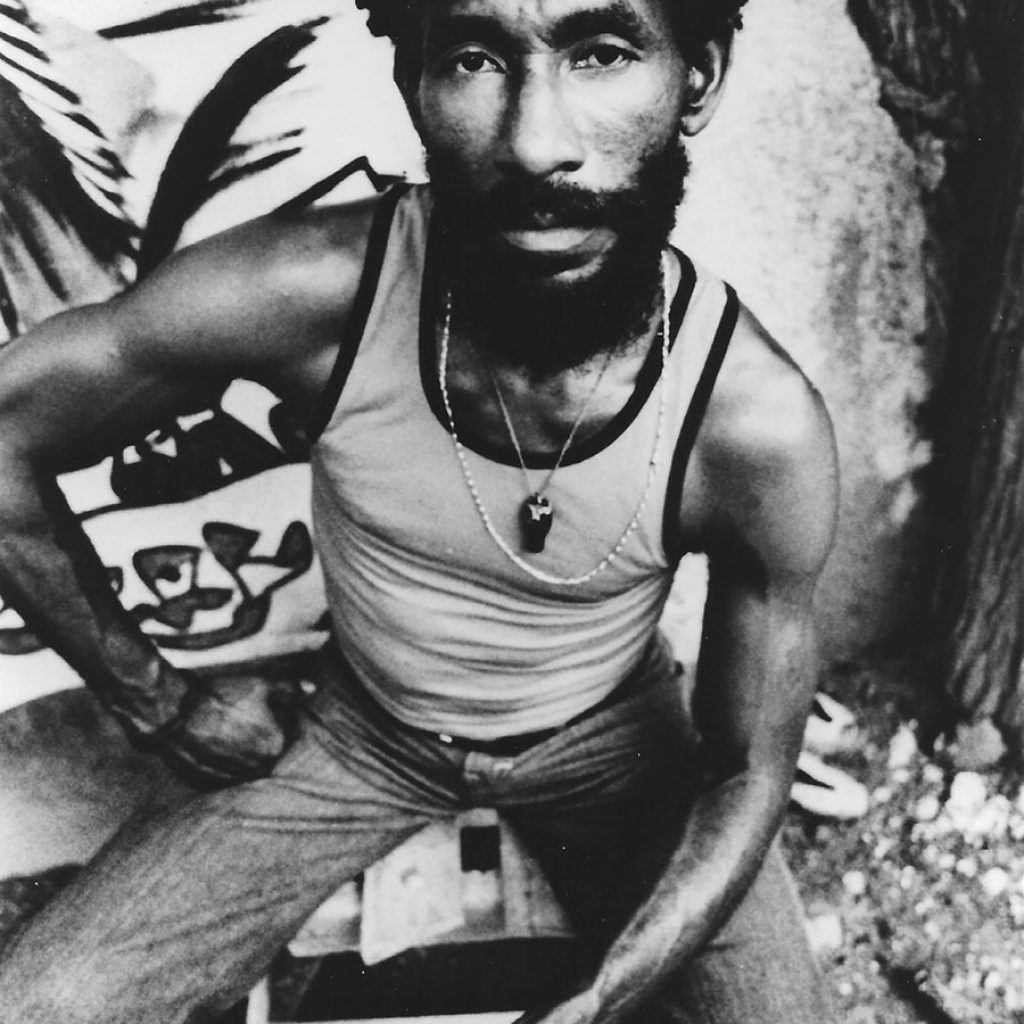

Lee “Scratch” Perry, one of the most influential forces of Jamaican music, died at the age of 85 on August 29, 2021.

There was no doubt about the notoriously eccentric Perry’s legend when he visited the Fox Theatre in Boulder in 1997. The innovative producer, songwriter and indie-label entrepreneur had been working since the ska genre, a precursor to reggae, began in Jamaica in the late ’50s. From 1975 to 1979, Perry made history, launching Black Ark, his four-track home studio in the suburbs of Kingston.

The period was being celebrated in Arkology, a gorgeous 3-CD set released by Island Jamaican Records. Arkology included such chestnuts as Junior Murvin’s “Police and Thieves,” Max Romeo’s “War in a Babylon,” several of Perry’s own (“Roast Fish & Cornbread,” “Curly Locks”) and other Black Ark recordings with Perry at the controls.

Perry also helped shape Bob Marley’s sound, and the Clash recorded “Complete Control” with Perry at the board in 1977. Perry had introduced himself to the members of the Clash after hearing their version of “Police and Thieves.” The meeting of punk and reggae was the inspiration for Perry’s next collaboration with Marley, “Punky Reggae Party” (a UK Top 10 single).

Stoked on rum, weed and Rastafarian sensibilities, Perry manipulated his primitive equipment to create deep, hypnotic reggae rhythms beefed up with pulsating reverb, futuristic electronic textures and scary noises. He was known for such studio antics as dressing up in a tree costume and blowing ganja smoke onto the spools of recording tape.

“I was only four (tracks) written on the machine, but I was picking up 20 from the extraterrestrial squad,” Perry, then 62, said in his thick Jamaican patois.

The radical productions proved visionary—many of the dub, hip-hop, rap and reggae techniques exploited by ’90s musicians were forged by Perry’s sound. But the Black Ark era was short-lived. In 1980, Perry apparently burned down the studio.

“Some funny things happen in Jamaica. I was amongst too many thieves and criminals, vampires. I could not take them anymore. I was not going back to reggae. I was not going backward to where I start. I was going forward into international music, making dub form.”

Perry began a self-imposed exile, living briefly in London and Amsterdam before settling in Zurich, where he lived for most of the ’90s. He collaborated with such contemporary deejays and producers as Mad Professor and Adrian Sherwood.

“But those are the past. No more work with them. Times have changed. I’m not interested in recording anymore, no interest in reggae music whatsoever. I lose too much money and too much time in it. All my years I didn’t get any money. Everybody else has my tapes. Every time I think about my tapes, it get me more mad, more angry. I do not intend to get back into it. I will not go back to Jamaica and make any reggae music. There is nothing there for Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry. I’m interested in tours and show biz.”

Yet Perry had been a rare presence onstage. “There was a problem with the visa, so there was no tour for me. I was not allowed to come in the States.”

But after a 17-year hiatus from America, Perry was performing once again. “Everywhere I tour is a big success. The vibration from the people is good for me everywhere I go, better than sitting in the recording studio, where you’re not getting anything.

“I am named ‘Scratch’ because all things start from scratch. So check it out—who am I?”