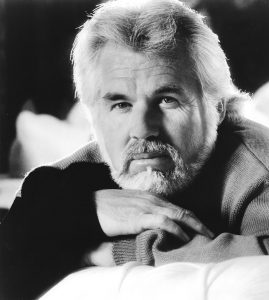

Kenny Rogers, the prolific country singer whose career spanned nearly six decades, passed away from natural causes on March 20, 2020, at the age of 81.

In the 1970s, Rogers became the biggest star in slick country-pop with such million-selling hits as “The Gambler,” “Lucille” and “Lady.”

But those huge successes evolved from his first hit with the First Edition, the mildly psychedelic “Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In).” Rogers had left the New Christy Minstrels, a folk/balladeer troupe, in 1967 and formed his own band.

“We were way ahead of our time—it was the wrong genre for us,” Rogers shared before an appearance at Denver’s McNichols Arena in 1983. “We were four members of the New Christy Minstrels who just sang background in the middle of the group, and they wouldn’t let us record on their sessions. We were going nowhere. One of the guy’s mother was a secretary for the biggest honcho in the music business, Jimmy Bowen. The old story is, the mother said, ‘Hey, my son’s putting a band together,’ and he said, ‘Well, bring them over and we’ll do an album.’ And that’s exactly what happened. We left on a Saturday night from Las Vegas. Monday morning, we were in the recording studio in Los Angeles.”

Rogers was on top of the world at the time of his ’83 Denver performance. The previous year had been a good one, with the release of his first motion picture (Six Pack), the success of his Love Will Turn You Around album and 135 performances. He also established the World Hunger Media Awards, “a Pulitzer Prize of sorts to bring attention to those people who are bringing the issue of world hunger to the American People.” He alluded to the turning point in his career, which had occurred at a Nashville country music festival nine years prior.

“A guy came up onstage and said, ‘Ladies and gentlemen, here’s a hit from 1956, “Crazy Mama”!’ The place went crazy. I said to myself, ‘A hit from 1956 and they still remember it? That’s where I want to be, right here with these people!!’” he recalled. “I was raised with country music; I feel comfortable with it. I’m in an unusual category. I was in jazz for nine years, folk music for two. I’m basically a country singer who’s had a lot of other influences.”

At that year’s American Music Award presentations, Rogers had claimed three trophies—Favorite Country Single for “Love Will Turn You Around,” Favorite Country Vocalist and a special noncompetitive award of merit for “his rise to the pinnacle of the music industry.”

But his thoughts were on a new album, We’ve Got Tonight, and he credited the sophisticated sound to producer David Foster (who had worked with Chicago, Earth Wind & Fire and Hall & Oates). Many industry insiders had wondered why Rogers had worked so hard on his final album for Liberty Records before entering into a new recording contract with RCA Records (the largest record deal in the history of the industry). Artists often finished their obligations to a label with a live album or a greatest hits compilation.

“As corny as it sounds, integrity is very important to me,” he told me. “I think if I sloughed off on this album, it might have helped my first album on RCA come out sooner, but a few albums down the road RCA would start wondering what their last album would sound like. You can’t start a relationship until you end one. I figured I owed Liberty the best album I could give them. It helps everybody, including my fans, if I do quality work.”

Indeed, Rogers’ following was notoriously faithful because of his commitment. The same commercial sensibilities his detractors cited were the ones that his fandom depended on.

“My feeling is that you should touch as many people as you can with whatever you do,” he reasoned. “I was talking to a critic who has always slammed me, because he’s a country music purist—he likes Willie Nelson, Emmylou Harris and so on. I told him that I understood his frame of reference, but I believe I am the ultimate purist—I am a pure commercial artist. If I don’t think something will sell, I won’t do it. I did two albums that were aesthetically beautiful, the best albums I’ve ever done—and I couldn’t give them away. I’ve got to sit back and think, ‘Why should I waste my time?’ I chose to do music instead of real estate or plumbing, and I’m a fool not to try and do as well as I can in my chosen field. Anyone who doesn’t understand that just has a different reference point than me. I don’t have to prostitute myself, and I don’t think I have.”

Rogers enjoyed success as a duet-partner with Kim Carnes (“Don’t Fall in Love with a Dreamer”), Sheena Easton (“We’ve Got Tonight”) and Dolly Parton (“Islands in the Stream”), among others.

“It’s always been my theory that you need to do a duet every so often just to break up the sound monotony, because you can only disguise your voice so many ways,” Rogers noted. “It allows you to have continued product out without the oversaturation of your sound. Plus, people feel like they’re getting something extra when there’s two artists they like on a record.”

When he performed at Denver’s CityLights Pavilion in 2002, Rogers was 63 and still wasn’t done. Recording for his own independent label Dreamcatcher Records, he had unexpectedly found himself with a smash in 2000—“Buy Me A Rose,” his 22nd No. 1 country hit.

“I’m like a boomerang. You can throw me away, but you can bet I’ll be coming back,” he said. “I’ve always said the problem with ‘new young country’ is its built-in obsolescence. You can only be new once and young for a while. It really didn’t leave me any place to try. But to radio’s credit, they heard a great song and they played it, and that’s all you can ask.”

And that was just the musical side of Rogers. At that point he also published a children’s book he co-wrote, Christmas in Canaan, and portraits from his photography book, This Is My Country, were on exhibit at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville.

“I have this theory that success in one field doesn’t necessarily guarantee you success in another, but it gives you an opportunity to experiment at a very high level,” he said. “Every January, I’ve said, ‘I want to do something this year that I’ve never done before.’ One year I went sky-diving, another year I bungee-jumped…”