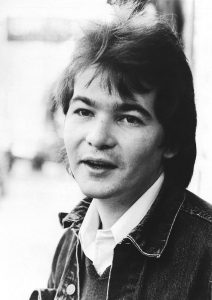

John Prine, the man responsible for some of the most articulate and moving songs of the last 50 years, died due to complications related to COVID-19 on April 7, 2020. He was 73.

Born in 1946 in Maywood, Illinois, a working-class Chicago suburb, Prine developed an early interest in music, particularly country and rock ’n’ roll. His older brother Dave taught him to play the guitar.

“He showed me how to play a chord, and when I finally played that chord without muffing—well, I just sat there with my ear on the wood, even after the sound died, just feeling the vibrations,” Prine said. “From then on, it was me sitting alone in a room, singing to a wall. The wall seemed to like it.”

Prine first visited Colorado’s Front Range in 1972, performing at Marvelous Marv’s in Denver and Tulagi in Boulder, forging a reputation as a songwriter and performer through songs that were simultaneously detailed, cynical and funny. The prime Prine was found on John Prine, his acclaimed debut album—“Sam Stone” (about the abuse of Vietnam vets), the wry ballad “Donald and Lydia,” “Illegal Smile” (an ode to recreational pot smoking), the anti-war song “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You into Heaven Anymore” and the much-covered “Paradise,” a nostalgic anthem against strip mining in rural Kentucky (where his folks had lived).

Prine had not only worked as a letter carrier for the post office but served in the Army, experiences reflected in his poignant and trenchant songwriting.

“I wrote a good deal of my first album on my mail route,” he recalled. “Once you’re on the right street, it’s like being in a big library without any books. Without bad weather or the occasional dog, it’s mundane.”

Prine continued to produce rewarding and compelling albums in the 1970s while confronting the label of “the new Dylan.” He steadily and decisively distinguished himself. His songs were recorded by many top country, folk and rock performers—notably Bonnie Raitt’s cover of “Angel from Montgomery” and Bette Midler’s version of “Hello In There”—and he developed a widespread, loyal audience through club and concert tours and television appearances.

Mass popularity eluded him, however. He came to be regarded as a minor cult figure, and his disappointment was palpable. But he remained thoughtful and amused by life.

“When I made Bruised Orange, the record label gave me crates of oranges as a promotional gimmick,” he said. “So I made Storm Windows, hoping they’d give me new windows. That’s also why I made the Pink Cadillac album, but I never did see a car—not even to pick me up at the airport.”

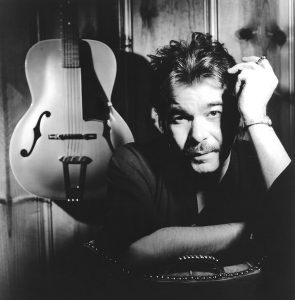

When Prine performed at the Rainbow Music Hall in 1986, he had a more unconventional image—as a “respected record company president” releasing albums on his own Oh Boy Records. The independent approach to the music business suited him just fine.

“I feel like I own this little hardware store—I make the music, I design the album covers, I follow everything all the way through,” he enthused. “And the people I sell it to are the people who enjoy it—it’s like we made a deal without those middlemen twirling their mustaches. It makes me want to work more than I ever did before.”

The formation of Oh Boy partially resulted from Prine’s move to Nashville from Chicago. “My girlfriend was living (in Nashville) and became my bass player,” he explained. “Then I married her and lost a bass player, but gained a wife. That’s the reason I moved in the first place—it was a total accident on my part. If she’d have been from Idaho, I’d probably be eating a lot of potatoes now.”

But Prine ensconced himself in the Nashville musical community, and the title of German Afternoon, his tenth album, was full of meaning—at least to him.

“It’s one of those days where you go out around one o’clock to get a burger or something, and you run into somebody you see all the time and have a beer with them. And somebody else comes in that you both kind of know but not that well. And because this third person comes in, you start buying each other beers. And the next thing you know, you’re late for dinner. That’s a German afternoon. A lot of the songs were written under that kind of duress—‘What happened to the day?’”

But where did the phrase itself come from? “Oh, I just made it up—I like the sound of it,” he laughed. “I got into the habit of telling my friends, ‘Let’s go have a German afternoon.’ These things have to start somewhere.”

The offbeat “Linda Goes to Mars” was typical of Prine’s exquisite vision, but following the fine low-key, low-budget album, he seemed on the verge of pulling a disappearing act. “I toyed with the idea of going back to school,” he admitted.

When Prine performed at Denver’s Paramount Theater in 1992, the mainstream had finally caught up with him. The Missing Years had won a Grammy Award and sold rapidly. Help had arrived in the form of Howie Epstein, the bassist for Tom Petty & the Heartbreakers and a longtime fan. He and Prine drew on old friends for the album (Petty, Raitt and Bruce Springsteen added background vocals), and the song “Big Old Goofy World” showed that Prine’s writing was at its bittersweet best.

Prine also had a featured role in Falling from Grace, a movie produced and directed by John Mellencamp. He played “the apologetic brother-in-law, the guy whose pants are a little too short and whose pockets are a little too tight. I’d been asked back in the 1970s to be in movies, but they were ex-convict or biker movies, so I took a pass on them. Now I’d like to do some Wallace Beery remakes.”

Prine beat cancer twice, having a tumor removed from his neck in 1998 and part of his left lung in 2013. He was elected to the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 2019, and in early 2020, he received a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammy Awards ceremony. The recognition as one of the most deeply respected and prolific artists in Americana music was occasion to reflect on comments Prine had made in the late 1970s.

“My dad was a tool and die maker,” he recalled. “He became president of the United Steelworkers Union local in Maywood and held down the post for 15 years. He was real big at the union—helped organize it after he left Kentucky. He was a great guy—56 when he died. He left us a bunch of dirty jokes with his will. Me and my brother found his will and sat around reading all these sailor’s jokes. My mother’s father ran a ferryboat on the Green River in Kentucky. When somebody couldn’t afford a regular preacher, they’d get my grandfather to say a few words, because he was a good man.

“In a way, things ain’t really that much different than the way they were when I was six or 16, just different people and I travel a lot more. I’d like to grow into the kind of good man my grandfather was, somebody who people would want to say a few good words over their dead body. So if I take care and live to be 50 or 60, I should be feeling pretty good by then, rather than remorseful or regretful. I’m just trying to find out which things really mean a lot to me so I can hang on to those, whether they’re just feelings or dreams or whatever. If dreams are good to me, then hang on to that dream.”