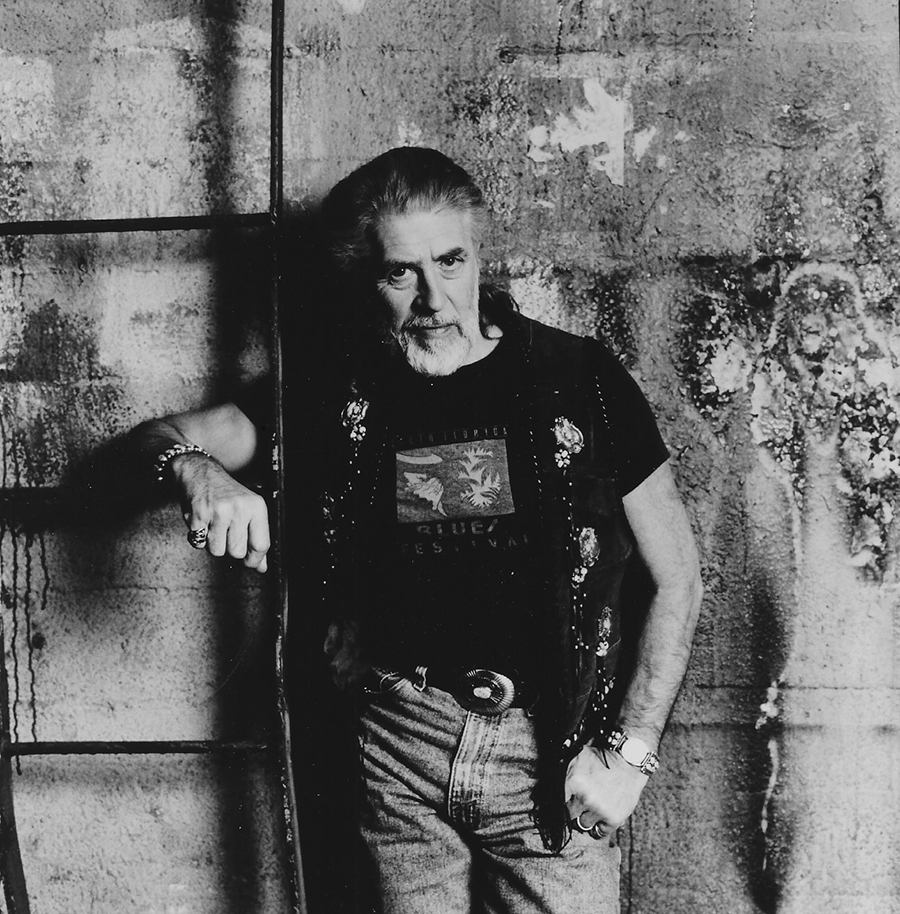

John Mayall, a legendary British blues pioneer, died on July 22, 2024. He was 90.

He earned the title in the Sixties, but Mayall remained “the godfather of the British blues scene” over the course of a career that spanned 60 years and more than 70 studio and live albums—“So far back, I’m surprised anyone bothers to count,” he laughed.

The tireless Mayall seemed destined to be remembered more for the people he groomed for stardom than for his own contributions to the development of rock music. In the mid-’60s, his successive bands of Bluesbreakers effectively acted as a finishing school for many of Britain’s leading instrumentalists. The original lineup, considered the first important British blues band, featured Eric Clapton on guitar. At various points, his disciples who graduated from the Bluesbreakers included Peter Green, John McVie and Mick Fleetwood (later of Fleetwood Mac); Jack Bruce (of Cream); Mick Taylor (who replaced Brian Jones in the Rolling Stones); Andy Fraser (Free); and drummer Aynsley Dunbar.

“I was a little older,” Mayall explained prior to a performance at the Boulder Theater in 1988. “This lucky generation has access to rare things, things that were unattainable to us back then. Everybody had to find their own path. My father’s record collection was jazz, and I knew the history of American music from reading books. I knew what to look for. I started off by collecting 78s. Bit by bit things became available.”

When blues music was just gaining a foothold in ’60s Britain, young bands such as the Rolling Stones covered material by American blues greats Muddy Waters and Jimmy Reed. “Pop wasn’t played in the clubs—traditional jazz had ruled there for almost 10 years,” Mayall said. “But there were a few elements of blues, small quartets, within some of the bands. And the blues grew out of that and replaced the trad jazz scene.”

Mayall’s name soon became synonymous with classy British blues, even though the singer/keyboardist/harmonica player was 30 years old before he put together his first band. “It’s not where you come from that’s important,” he said. “It’s what you hear in your head and what you put out through your instrument.”

Indeed, for a time Mayall battled a reputation as a frugal eccentric, as he had once lived in a tree house. “But the motivation was the opposite of being a recluse,” he explained. “I lived in a crowded house with a large family, and I wanted my own room, so I built it up a tree. Of course, I used the house for the main facilities. I’ve never been like Jesus in the wilderness, but if anyone wants to think that’s eccentric, fine.”

Mayall moved to America in 1969, and during the ’70s worked increasingly in a jazz-blues style. He assembled a new Bluesbreakers lineup that ranked as the longest-lived configuration of any Mayall band. Two hot and hungry soloists, guitarists Coco Montoya and Walter Trout, provided the creative energy. The band averaged more than 120 shows a year in 15 countries. “It’s pretty hard to imagine blues fans out there in Romania and Turkey, but it shows you how the blues is spreading throughout the world.”

Purists felt an aversion to Mayall—as a singer and player, they considered him pedestrian, and he was white and British, not an African-American. But over the years, few artists remained as steadfast to their love and study of the blues. By the early ’90s, the 60-year-old qualified as a luminary, giving a state of the blues address following a concert at the Denver Zoo. “It’s very healthy,” he said. “In the early years, you’d get interested in a player and he dropped dead from self-abuse—that was the destructive factor in the ’60s. Nowadays, with all this new interest in the blues, the players aren’t about to let it slip through their fingers. The practitioners who are in the forefront are playing with great conviction at the peak of their careers. People write about where you come from out of convenience, but it transcends that. As long as you stand apart as a recognizable performer, that’s the key to the blues. Nobody can come close to sounding like John Lee Hooker or B.B. King, even if they play the same notes.”

Mayall harbored no regrets that many of his alumni became better known than he did. “I’ve never looked at my band in the same way other people have,” he said. “I’m not training musicians out there like a coach who trains athletes to go out for the Olympics. I put bands together for the enjoyment of all of us. I have no way of getting in touch with Eric Clapton other than the general public would—he’s never seen a show of mine. But there are people you bump into—Mick Taylor and Mick Fleetwood are in the picture. Hopefully we’re outgrowing those critics, those old dinosaurs who can’t see past the sidemen who went on to bigger things. Today’s audience of 18-year-olds hasn’t heard John Mayall’s music until they’ve heard a new album.”