Singer-songwriter Jimmy Buffett, whose brand of laid-back island escapism on hits like “Margaritaville” and “Cheeseburger in Paradise” made him a hero to devoted fans known as Parrot Heads, died on September 1, 2023.

Raised in Alabama, Buffett had never seen the mountains until a friend from Colorado’s Timberline Rose turned him on to the Rockies in the early ’70s. “I had been up to Montana to visit people, but I hadn’t spent a long period of time out West,” Buffett said. “Denver was the first place I went on tour—I got out of humidity and came to the mountains to play. The Cafe York on Colfax was my first gig in Colorado.”

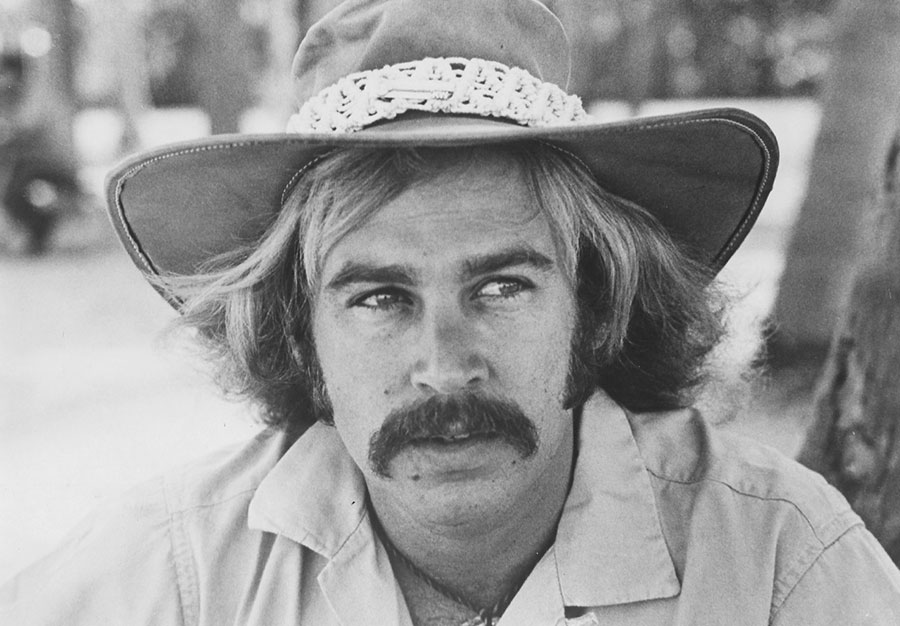

Dressed in Levis and a cowboy shirt, his hair long, Buffett carried his two Martin guitars from the small coffeehouses to college campuses. There, with a distinctive southern-flavored accent, he entertained. “No flashing diamond rings, no skin-tight tuxedo, no Las Vegas marquees,” he said. “I lived in a little sleazy hotel in metropolitan Denver, and then I went to the mountains, as everybody has done—up to Evergreen, Bailey, then Breckenridge where I did the summer mountain circuit, having a glorious time. I wound up the tour in downtown Pueblo, not known as the most beautiful spot in Colorado. But seeing every side of Colorado eventually led to me settling there for a while.

“Circa 1971, when I was doing my mountain touring summers in Colorado. I’d gone out to San Francisco and was living in a Howard Johnson’s in Marin County. I left my girlfriend, who later became my wife, in Aspen. I was thinking about her and I wrote ‘Come Monday.’” The song became Buffett’s first hit single in 1974. The song “A Mile High in Denver” eventually appeared on Buffett’s Before the Beach album.

The artist made his home in Aspen for many years before relocating to the Caribbean. “Most people always consider going to Colorado for the winter, but my attachment was a summertime thing,” he testified, having made yet another survey of Aspen’s bars. “There’s so much to do.”

With the million-selling Changes in Latitudes, Changes in Attitudes, Buffett’s following had swelled gradually to reach major proportions. “Margaritaville” was a perfect example of his charming brand of let’s-go-down-to-the-Caribbean lifestyle, and its huge popularity shot him into the national spotlight and cemented his status as a Colorado favorite. He considered his Red Rocks Amphitheatre show in 1977 as the greatest of his career to that point. For his 1978 concert at McNichols Sports Arena, Dan Fogelberg came down off his mountain to join the band for an encore; Buffett had the entire audience hanging on his every word. His appearance at the CU Events Center in 1982 was notable as singer Katy Moffatt returned to Colorado as a backup singer in his entourage.

By 1985, Buffett was still a performing animal first and foremost, maintaining his status as a top-drawing concert attraction. As part of his show at Denver’s Mile High Stadium, the Denver Symphony Orchestra joined him and his Coral Reefer Band on stage for three songs. But he’d recently diversified—he’d finished a screenplay for a long-rumored film version of Margaritaville and opened a store in Key West called Margaritaville, selling all sorts of Buffett paraphernalia and merchandise, including his own line of “Caribbean Soul” clothing. His Last Mango in Paris album contained an entry form to win a cruise aboard Buffett’s yacht for three days.

But radio ignored his music in the ’80s. “It stands for the quality of our stage show that when the record business went a different direction from where we were, we kept going,” he shrugged. “Hey, you know me—I never work too hard. When the weather’s beautiful, I’m on my way to the golf course.”

In 1986, for a special Sunday afternoon concert, the only daytime gig on his Floridays tour, 9,000 Parrot Heads crammed into Red Rocks Amphitheater in the midday heat. “They know every word to every song I ever wrote,” he marveled. “They seem to be relatively normal people most of the time—but when they come to my shows, they put on their ‘feathers’ and go nuts.” The show resembled an oversized backyard barbeque—the Hawaiian shirts were off, imbibing was mandatory—and Buffett maintained his usual upbeat atmosphere for his following of “cultural outpatients.” “I haven’t seen this much white meat since Thanksgiving,” he surmised.

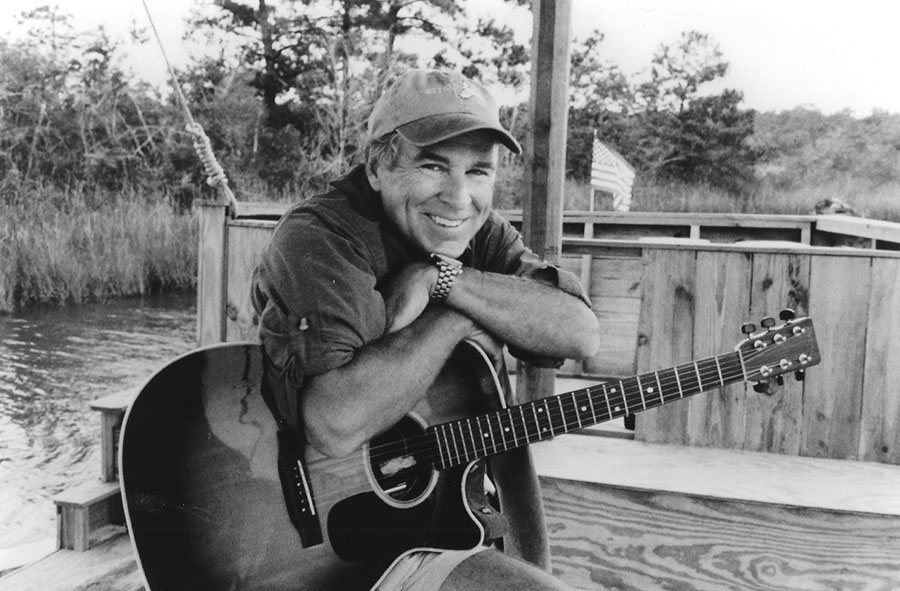

The tropical rocker performed two shows at Denver’s Fiddler’s Green in 1988. “You can be the president of the band or work at the 7-Eleven, but on that day when I come to town, if you’re a Parrot Head, you can act pretty insane—and get away with it.” The “son of a son of a sailor” had added a new element to his lifestyle by piloting his own seaplane, a Lake Aircraft Renegade. “Flying gives you total freedom,” he said. “I haven’t given up sailing, but when you’re up there, you can really let go of things. The plane’s opened up—pardon the pun—a lot of horizons for me.”

Many fans assumed Buffett was the laid-back, carefree character portrayed in his songs, but his protean output revealed an industrious side. He was also an author (The Jolly Mon, a children’s book), an environmentalist (chairing and doing major fundraising on the Save the Manatee committee) and a restaurateur (his “Margaritaville Café”).

“I basically run it like a boat,” he said of his business empire. “The secret is to find competent people to work for you, to keep it within a family. A lot of folks who were on the road with me for years decided they didn’t want to tour anymore, so they stay home and run the Florida businesses for me.” He had aborted plans for his Margaritaville movie. “I’m gonna take a little more time off next year and work on my book, because with a book you don’t have to have meetings with accountants and lawyers. If I want Godzilla to eat the conch train, they can’t tell me it costs too much.”

His 1989 summer tour came to Denver’s Fiddler’s Green Amphitheater for two sold-out shows. “This is the 17th consecutive year I’ve gone out on tour and wound up in Colorado,” he said. “I’m glad people have liked me for so long, because I don’t want to remake myself. But even when you’re sailing in one direction, you still have to tack a lot. In other words, every now and then you’ve got to scrape the roux off the bottom of the gumbo pot—it makes it better.”

He was so pleased with his 17th album, Off to See the Lizard, that he finished a collection of 16 short stories that Harcourt Books published, titled Tales from Margaritaville. “I wanted to be a writer long before I ever thought about music, so I’m real proud. I finally used my journalism degree (from the University of Southern Mississippi). I forgot how much motivation putting Catholic guilt in front of a deadline was.”

At a winter book signing at Lakeside Mall, 1,500 people came in freezing snow. “It was overpowering how everybody expressed their opinion as to where I should play in Denver—which is Red Rocks. It was definitely on their minds, so I listened intently to them. If we’d have gone back to Fiddler’s Green, I think people would have started not coming. I wanted to play Red Rocks if I could get reserved seating instead of general admission, because G.A. is a combat zone in the front rows. It’s fine if people want to camp out all day, but if that’s what I’ve got to play over to get to the other 90 percent, it’s hell up there. I know reserved seating makes for a better show.”

And that’s what he got for two nights at Red Rocks in 1990. “I saw some shows this year that my daughter is interested in. I won’t name names, but one begins with an ‘M’ and ends with an ‘a.’ And the lack of true performing sense that’s out there really dawned on me. A show is considered good if somebody actually sings live! I guess I’m showing my age, but to me, lip-synching in performance is appalling, the lamest excuse. It’s just fear—the point of being a live performer is taking the risk that anything can happen.” Instead of playing golf or sailing before showing up for days of rehearsal, he worked for weeks enhancing his show, dissecting harmonies and beefing up theatrics. “My daughter paid me the ultimate compliment. She said, ‘Dad, it sounds so good they’re gonna think you’re lip-synching.”

Buffett did return to Fiddler’s Green for two nights in 1992. While delegates at the Republican convention in Houston were supporting President Bush, the sold-out audiences at Fiddler’s boosted the campaign of another nominee with “Jimmy Buffett for President” bumper stickers. “My success is still unexplainable. I defy all odds—no hit singles, no videos, and I’m the top concert draw in the country. I’ve done it my way—I haven’t taken a summer off in 20 years, and it’s paid off. I’ve regenerated my audience—I’m 45 and the demographics at my shows are getting younger. I’ve got the war babies’ babies.” He was playing “A Mile High in Denver” in his sets. “It’s dated, but sort of funny—I guess you could say I hear the potential,” he laughed.

By 1994, when he played Fiddler’s Green for two nights, he was a record company CEO (his Margaritaville Records) and a best-selling author (Where Is Joe Merchant?, his novel about a seaplane pilot investigating the disappearance of a rock star in the Caribbean). And he’d begun working with Herman Wouk on a stage musical based on Don’t Stop the Carnival, Wouk’s 1965 novel about a Broadway press agent who quits his job and buys an island hotel hoping to find paradise (he doesn’t).

Fans saw snow on the ground three days before Buffett’s two performances at Fiddler’s Green in 1996. “The October outdoor dates don’t bother me,” he said, wondering if the Parrot Heads would turn into Penguin Heads and the drinks they dragged out of their coolers would be frozen margaritas. But his musical with Wouk opened in April 1997 at the Coconut Grove Theater in Miami and had a seven-week run.

“I had no expertise in the theater, but it hasn’t been that hard to cross over,” he said before previews. “I’ve got 30 years of successfully navigating the waters of rock ’n’ roll, which is pretty similar. I said going in, ‘There’s nothing that I have not seen in maintaining a band that they could throw at me,’ and, so far, it’s rung true. My experience lies in the fact that I believe I’m a good showman, and that’s why I love musical theater as a consumer.”

By 1999, only six authors had reached No. 1 on both the New York Times’ fiction and non-fiction lists: Ernest Hemingway, John Steinbeck, William Styron, Irving Wallace, Dr. Seuss—and Buffett. Where Is Joe Merchant? had achieved No. 1 in 1993, and he reappeared at the top with A Pirate Looks at Fifty, a prose documentation of a three-week, 17,000-mile trip around the Southern hemisphere he took with his family upon turning 50 on Christmas Day 1996.

“It’s funny that I’ve never won anything for music, but the awards are selling out venues and going to the top of the best-seller list and selling tens of thousands of hardback books. You’re reaching and pleasing your audience. I’ve always run on my own set of rules and bucked the establishment in every way—but not head-on. I just wanted to do what I wanted to do. But when all of a sudden they can’t deny the fact that you’re successful—yeah, there’s a great bit of satisfaction.

“I don’t consider myself a musician—in the lineage from theologians, we’re descendants of court jesters. Our job is to make people happy. It’s not to save the world. The core of what I do is entertain. I can entertain on stage, or I can entertain in a book now.”

By 2002, Buffett didn’t expect to receive airplay between the teen-pop stars and rap-rockers of the world, but his ability to draw audiences hadn’t diminished. He did a show at Pepsi Center in 2003, and it was like his previous tours. Otherwise normal human beings came arrayed in hula skirts and coconut bras—women included. They drank beer until their aim got fuzzy, then hurled beach balls at the stage. They danced the land shark.

“I’m simply a working guy who gets up there to do a show and give everybody the bang for their buck—Southern work ethic meets Catholic upbringing,” he said with a laugh. “There’s no end in sight, so I’m going to ride it, keep doing exactly what I’m doing. People will tell you when they’re tired of you. You can never please everybody at once—they’re going to bitch about anything from ticket prices to not getting tickets to whether you’re doing their favorite songs. But as long as 99 percent of the people talk about how much fun they have, I’ve got to think I’m doing something right!

“How much more do I need? Nothing. But if you’re somebody that loves what you do, why would you quit? (Football coach) Don Shula once told me, ‘Jimmy, do it as long as you can. There are only so many fishing and golf tournaments you can go to.’”