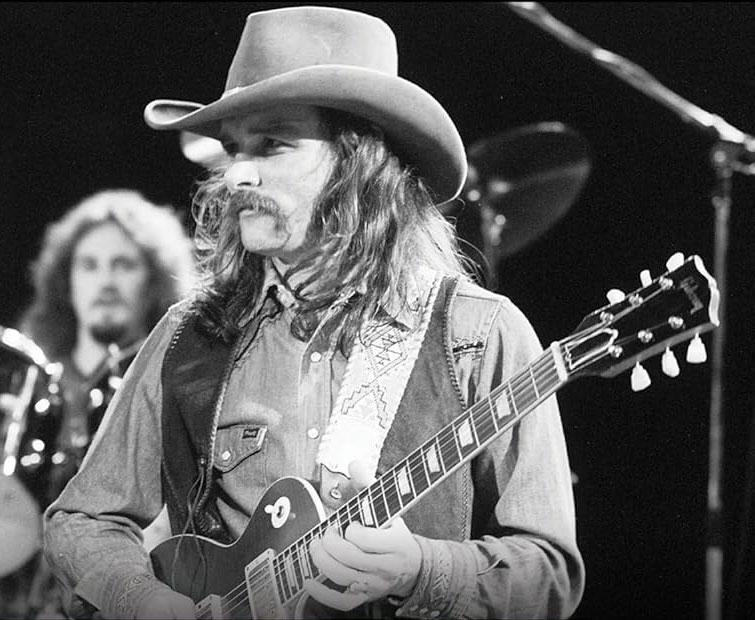

Dickey Betts, a founding member of the Allman Brothers Band and the fiery guitarist who wrote and sang “Ramblin’ Man,” the group’s biggest hit, died on April 18, 2024. He was 80.

The history of the Allman Brothers Band reads like a sorrowful opera. During the late ’60s and early ’70s, the group established a reputation for awesome playing skills, conjuring a mix of virtually every American musical form—blues, country, R&B, jazz and rock—bound by an ethos of soaring improvisation. The Allmans’ benchmark early albums remain noted for a graceful, unique interplay between Duane Allman and Betts, a gifted guitar duo. Live at Fillmore East ranks as one of the finest concert albums ever recorded.

But in October 1971, when the Allmans might have been America’s best answer to the British supergroups, Duane Allman died in a motorcycle accident at age 24. The band regrouped and continued to tour and enjoy success. Betts’ role became more prominent with his breezy “Ramblin’ Man,” the classic instrumental “Jessica” and the favorite “Blue Sky”—yet things were never quite the same. Brilliant instrumentation had taken the Allmans to the top, but the air of tragedy cemented the legend.

“Now it’s hard to talk about Duane without sounding like you’re being disrespectful,” the mannerly Betts mused prior to a stop at Red Rocks Amphitheatre in 1991. “Duane was one of the greatest I’ve ever seen, and he deserves all the things ever written about him, for sure. But it’s hard as long as you’re still alive and out here chopping away at it—you don’t seem to be immortal. You can never measure up to that Duane Allman thing because he was killed at that early age. That was pretty tragic, and it’s mysterious and romantic. I’m glad to be here, and of course I’m glad to have played with Duane—I’m not complaining at all. But it’s a touchy question.”

The band had survived the deaths of Allman and original bassist Berry Oakley, the vagaries of substance abuse, legal wrangling and what appeared to be an irrevocable split suffered in the mid-’70s, when the band severed all ties with singer Gregg Alllman after he testified against his personal road manager, who received a 75-year sentence on narcotics charges. “There is no way we can every work with Gregg again,” an aggrieved Betts said at the time.

The beloved group endured rifts, breakups and reformations throughout the ’80s before coming together again in 1989, re-earning a place in the rock pantheon and reaffirming the old spirit with a signature blend of blues roots and virtuoso jamming. The band returned to its original instrumentation—two-guitar magic from Betts and new member Warren Haynes, and Gregg Allman on keyboards. ABB was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1995.

“We’ve always been musicians—we’re not involved in show biz too much,” Betts allowed. “When we weren’t recording, we were still working and listening and experimenting, because that’s what we do. We didn’t quit playing during the ’80s and then come back from retirement. That’s made a lot of difference.”

Yet in 2000, on the eve of the band’s summer tour, Betts was forced out of the band by his longtime partners. In interviews, Gregg Allman claimed that Betts’ drinking and drug use interfered with the band’s performance. Meanwhile, cynics wondered whether Allman, who’d fought an alcohol problem for years, was pot or kettle.

After being relieved of his duties, Betts formed a new group under his own name and toured, performing at the Telluride Blues and Brews Festival and the Ogden Theatre in 2001. Meanwhile, the Allman Brothers Band played to half-filled houses. For many devotees, paying to see the Southern rock stalwarts without Betts—the backbone of the band along with Allman—was akin to seeing the Rolling Stones minus Keith Richards.

“I tried my best to talk them into having a farewell tour if we were going to fly apart at the seams, (so) we can leave the Allman Brothers Band intact for history,” Betts said, sounding sober and assured. “Let’s not call it the Allman Brothers Band with only two members, like the Drifters have done for 20 years. And they would not listen. That’s the disappointing part. Everything that band stood for—taking up for one another, brotherhood—got hit with a pie in the face toward the end of our career. I would have loved to see us go out with a little more dignity than that. It’s really heartbreaking.

“Maybe one of the reasons the guys felt the need for a change was that (the spark) was disappearing from the band. Somehow I became the person…if I wasn’t in the picture, everything would change for the better. I had no choice but to change. I’m making a tenth of the money working four times as hard to be able to pay the guys in my band. But on the other hand, they are making twice what they ever made—it’s the best gig they ever had! I guess it all works out.”