During the halcyon years of the Colorado Avalanche, nothing pumped up Stanley Cup-crazed fans more than the aggressive instrumental guitar sound blaring over the P.A. as the team took the ice at McNichols Arena. It was “Scalped” by Dick Dale, the “King of Surf Guitar” (the nickname his old fans remembered) and the “Sultan of Shred” (as alternative rockers anointed him in the ’90s).

Using “Scalped” as a crowd-rockin’ hockey anthem was the brainchild of a “Dick Head” in the Avs organization. “In the playoffs, when the team was the underdog, they invited us up and we were going to try to play it,” Dale explained in 1997. “But we couldn’t get a platform set up in time. They gave us box seats, and what an experience—it was unbelievable. ‘Scalped’ is their fight song, and it gave me chills.”

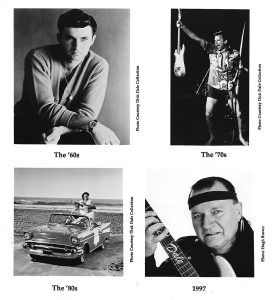

On March 16, 2019, Dale died at age 81. His career could be traced from the ’60s, when he developed surf music, to the ’90s, when his influential instrumental style launched him to cult-hero status with the college-rock set. In 1994, he paid for his own video of “Nitro”—and the clip (the first of his career) was on MTV’s 120 Minutes and Beavis and Butt-Head.

But Dale wrote “Nitro” for snowboarders, not surfers—the guitarist had been reborn as an environmentalist. “The snow hasn’t turned yellow yet,” he said. “I used to be in the water from sunup to sundown, but I take my son down to where I used to surf and there’s fecal matter floating in the water. Now I live in the high desert, 2,000 feet above sea level.”

Dale had a place in the rock ’n’ roll pantheon for inventing a unique and influential electric guitar technique. In 1954, as a high school senior, he moved from Boston to southern California. He loved to surf, and his fast, heavily reverbed staccato playing duplicated the physical sensation of riding a wild wave.

“I learned to play guitar like Gene Krupa played drums, that same percussive rhythm. It melts picks—I’m playing on heavy-gauge strings to get this fat sound. Most players play on 6s to 9s. My smallest gauge is a 14, and it goes to a 60—they’ve been called telephone wires, bridge cables and coat hangers. It drags my pitch down into my fingers. People go, ‘God, the faces you make!’ Those aren’t faces, that’s pain—when you start pulling and sliding up and down on those big strings, it’s like putting your hand in a grinder.”

In 1960, Dale formed the Del-Tones and quickly became popular in California. His first single, “Let’s Go Trippin’,” was a regional smash in 1961. “Miserlou” became his signature song. Dale was also on top of technology, testing prototypes of Leo Fender’s new gear before they went into mass production.

“Before me, speakers were for county players—I burned up those 7-inchers. I co-invented the Fender Twin Reverb—it was the first amplifier that could take the punishment that I gave out every night.”

Dale’s in-your-face attack was never captured in the studio. “I quit recording because the engineers couldn’t record my guitar—they suppressed it and made it sound tinny. So every one of my records was junk.”

In 1966, Dale suffered from intestinal tumors and retired from performing. He was initially pronounced incurable, but he was successfully operated on. “Then I went to Hawaii and met some martial-arts masters. Studying with them kept me alive and gave me a new outlook.”

He spent the ’70s as a California nostalgia act, and he fell on hard times in the ’80s. He lost his nightclub in a divorce settlement, and he suffered severe burns over much of his body in an accident.

In 1987, the soundtrack album from the movie Back to the Beach featured a Dale duet with Stevie Ray Vaughan (it received a Grammy nomination). Guitar Player magazine proclaimed him “the father of heavy metal,” and his muscular technique was detected in the work of rockers such as the Ramones and Sonic Youth. Director Quentin Tarantino selected “Miserlou” as the theme song of his 1994 film Pulp Fiction. Dale was 59 when he gained instant popularity among alt-rock fans on the Warped tour.

“I was grinding halfway through my picks before I gave them away to the crowd,” Dale said. “The police came and had to go, ‘Okay, you guys can have the show, but we’ve got to put a limiter on one band—Dick Dale. He’s doing about 125 decibels.’ The headlines read ‘Dick Dale Outpunks the Punks.’ In Australia, they called me ‘Louder than Motorhead.’ In Japan, they call me ‘Monster Monster Godzilla.’

“If it wasn’t for Dick Dale, there wouldn’t be a Van Halen, a Joe Satriani, a Jimi Hendrix—the power players. Dick Dale doesn’t play surf music. The Beach Boys and Jan & Dean play surf music. Dick Dale plays the ocean, he plays the lions and tigers, he plays the power of Mother Earth. That’s what I emulate.”

When Dale came to Denver to perform at Herman’s Hideaway in 1994, it was part of his first tour outside of California.

“I’ve dedicated myself to doing this. How many more years do I have left going like a madman onstage? I’ve got a message to get out there,” he said to preface a half-hour discourse on strip-mining, mercury levels in tuna, the rainforest, endangered species and chemically treated beef. “I’m building a big tribe, just like Johnny Appleseed. It’s like a family all around the country, following me everywhere. All ages, all walks of life like the sound.

“When I die, it’s not going to be in some rocking chair, emulsifying like some leaf. It’ll be in a big explosion onstage. There’ll be body parts…”