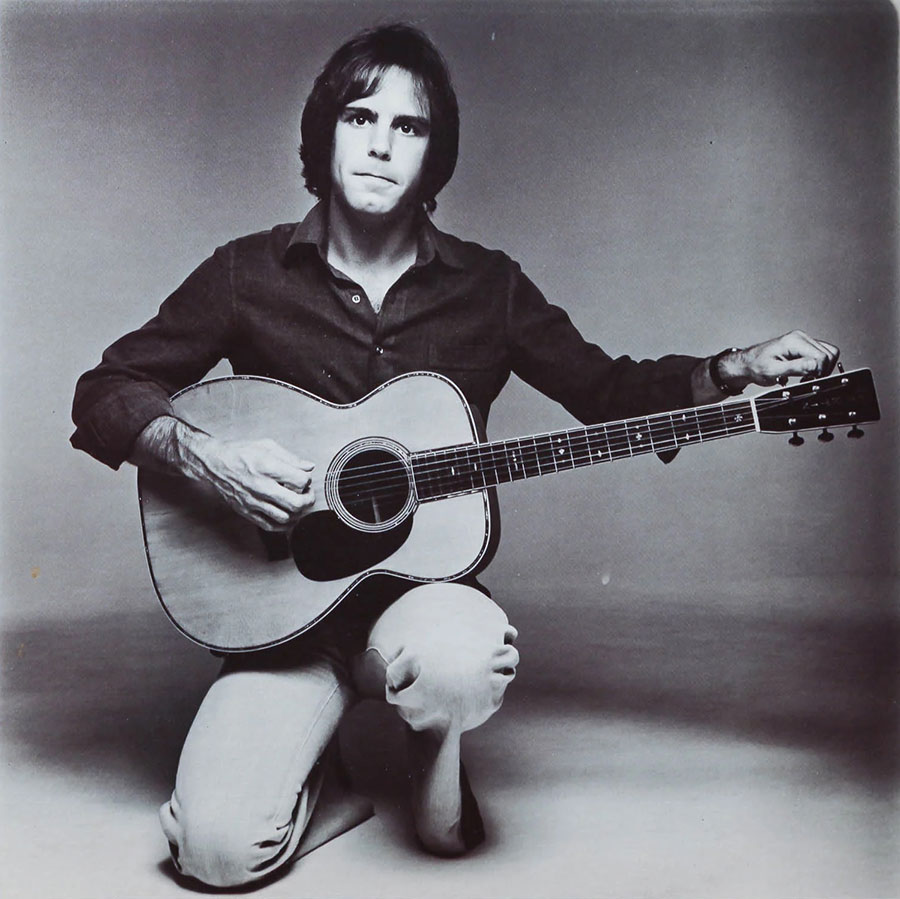

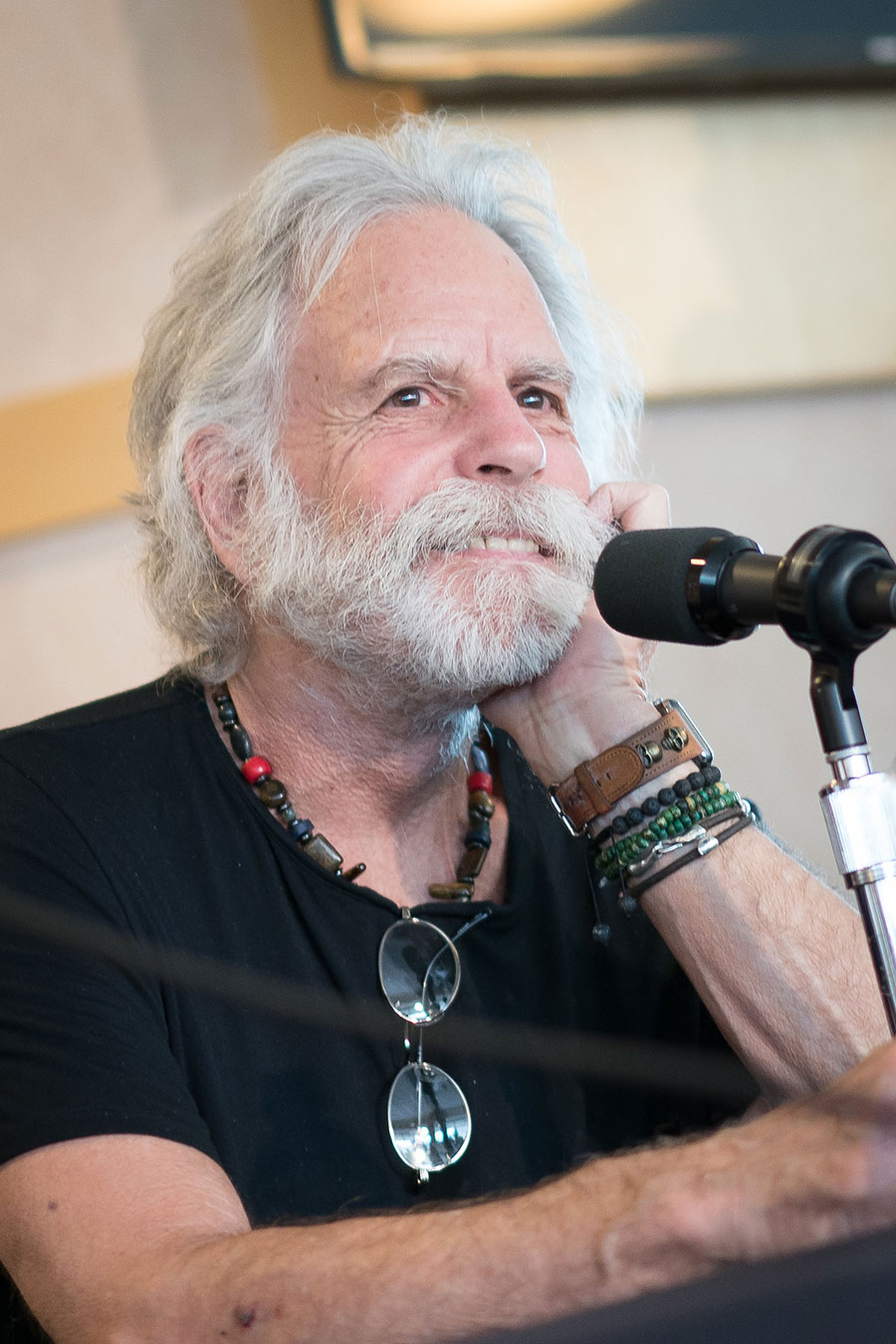

A founding member of the Grateful Dead, Bob Weir passed away on January 10, 2026, at age 78.

Within a few years of its founding in 1965, the Grateful Dead became a force within the counterculture, its style shaping rock music. The San Francisco band’s storied history in Colorado began at Denver’s Family Dog and a “Human Be-In” in City Park in 1967, the Summer of Love. “There was a mini-Haight Ashbury in most every place we went, but Colorado had a pretty thriving one,” singer, songwriter and guitarist Weir recalled. “A lot of crazies, a lot of bands.”

In 1969, a gig took place at Reed Ranch, a barn outside of Colorado Springs. Weir had a special connection to the city—he attended Fountain Valley School as a sophomore in high school, but he was asked to leave after a year, he said, for being “too rambunctious.” He was a member of the football team and met John Barlow—“He was the waterboy.” The two became lifelong friends and songwriting collaborators.

The members would go on to play the state’s legendary venues, with generations of Deadheads gathering to connect with them. In 1972, the Grateful Dead performed before approximately 32,000 fans at Folsom Field in Boulder, the band’s first stadium show in Colorado, marked by torrential rains and, at one point, hundreds of lids of pot were tossed into the air from the crowd and from the stage. “That was a crazy gig. It rained rain and ounces of marijuana,” Weir laughed. “Some generous and well-to-do benefactor, probably in that business, made sure that everybody got all the weed they could handle. And it rained the kind of rain that you expect fish would swim by. And we almost burned down the place—at one point, there was St. Elmo’s fire on the piping that held the stage up. Everything was enormously electrically charged (Owsley Stanley, the band’s wizard electrician and stage manager, had his own ideas about electrical grounding). But we lived.”

With the group’s first-ever performances at Red Rocks Amphitheatre in 1978, the Dead started becoming synonymous with the renowned outdoor venue. Weir and his bandmates considered Red Rocks “a sacred place” for their music, likening it to Stonehenge and the pyramids of Egypt. “I was awestruck by the place when I walked in,” he said. “You can use all the ‘power’ you can get up there, because you’re basically gasping for air if you’re singing, or playing a horn—you just don’t get a lot of air to work with up there.”

To celebrate the Grateful Dead’s 15th anniversary, Deadheads made the pilgrimage to Boulder’s Folsom Field for two shows—and the median age couldn’t have been more than 20. “I relate to those kids more readily than people who have grown old and stodgy—something I hope I haven’t done,” Weir explained. “If our older fans have outgrown us, I would pity that, because we’ve tried to keep a fresh approach to our music and life in general. If they’ve outgrown us, I welcome the younger fans. But that’s hardly true. We’ve got lots of fans in their 40s, and I like to think our music maybe has less of an age barrier than other presentations.”

The Dead certainly had the reputation, as Weir put it, of “putting on a helluva live show.” The band members never went onstage knowing what they were going to play, and their vast repertoire guaranteed that you could go to a Dead concert on consecutive nights and not hear songs repeated. “We’re getting better that way in that we’re more consistent,” Weir admitted. “That’s why people keep coming. But as far as how we generate so many new fans, I still don’t know how that happens. It’s a mystery to me.”

In 1985, a three-night stand of sell-out shows at Red Rocks marked the 20th anniversary of the Dead. While many of the uninitiated remained baffled by the band’s appeal, the Dead had sustained devotion among Deadheads still obsessed with the ineffable combination of music, ambience and other intangible factors that kept the live experience so compelling. Weir conceded what a long strange trip it had been—“We’re the exception to just about every rule in the entertainment business.”

In August 1992, Weir had just wrapped up his own tour when he called the Grateful Dead office and learned that leader Jerry Garcia was sick. It broke a long-standing tradition of nearly nonstop touring—the band canceled concerts and put other plans on hold to give Garcia time to recuperate. The lead guitarist rested at home, and the Dead resumed touring with two concerts at Denver’s McNichols Arena. No one had diffused the intense anxiety of Deadheads, so Weir patiently addressed the issue. Garcia had suffered a physical breakdown brought on from heart and lung problems.

“We lost track of what we were up to,” Weir noted. “You get involved in what you’re doing—what’s important becomes what’s happening onstage or in the studio. And you don’t look around and check out the other conditions of your situation—you’re getting tired, gaining or losing weight. I was starting to get pretty thin myself. There’s more to it than that. You have to keep your mind and your body in shape.” Weir kept busy while the band was idle. He and his sister Wendy, an illustrator, completed work on Baru Bay Australia, the follow-up to Panther Dream, a beautiful book for children about the African rain forest—Baru Bay Australia focused on Australian reefs and Aboriginal culture. He fought the Montana Land Management bill, which would have given 5 million acres to the US Forest Service to do with as it pleased.

In 1995, the Grateful Dead saw three decades of uninterrupted touring end with the death of Garcia. Everyone speculated about the future of the legendary band’s surviving members and millions of Deadheads. But the legacy lived on in the Furthur Festival, a traveling road show in the tradition of the Dead’s caravans. The event was highlighted by the presence of co-headliner Ratdog, Weir’s new band. Weir said he didn’t grieve for Garcia as much as he communed with his spirit. “This is just fun, same old deal. That’s what we’re out here to do, and by God, that’s what we’re going to do—have some fun.” The broad avenue of blues, jazz and R&B, the American music Weir grew up with, was near and dear to Ratdog, a collaboration with bass virtuoso Rob Wasserman, Matthew Kelly (a member of Kingfish, a hippie C&W blues band that Weir led in the ’70s), Jay Lane and the legendary Johnny Johnson, Chuck Berry’s original pianist. “We heard that Johnny was available—he’s still out of St. Louis—so we gave him a ring to see if he was up for it,” Weir enthused. “He’s a monster; he plays blues and jazz with an authority you’re just not going to find elsewhere. We’re jamming on songs he did 40 years ago like ‘Promised Land.’”

Ratdog’s influences moved from blues and Grateful Dead tunes to improvisational jazz. 2000’s Evening Moods was Weir’s first non-Dead studio release since the early ’80s. “It took us a while to get around to writing, because we were in a state of flux—every time a new guy would come into the band, we’d spend all the time we had teaching him the old book,” Weir explained. “Once the personnel stabilized, we got to it straight away.”

In 2001, Weir organized a bill similarly themed to Furthur dubbed So Many Roads, featuring Ratdog. The tour hit Red Rocks Amphitheatre. Weir had hurt his left hand a week prior when he fell through a glass table; he received four stitches and had played shows since. Weir founded and played in several other bands during and after his career with the Grateful Dead, including Bobby & the Midnites and Furthur, which he co-led with former Dead bassist Phil Lesh.

In 2015, Weir, along with former Dead members Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann, formed the band Dead & Company; the band performed multiple dates at Folsom Field, Red Rocks Amphitheatre and other Colorado venues. “People make a point of setting up vacations so they can come and hear us play in Colorado,” Weir said. “That adds to the event quality—it’s a big occasion for a lot of people. They’re in a glorious celebratory mood. That helps! We feel that vibe, and we work with that. And aside from that, Colorado has always been my second home. I love the place.”