In the 1990s, Pearl Jam had its turn as rock’s hottest new band. The Seattle quintet’s debut album Ten sold more than five million copies in the United States. In late 1993, the Vs. album debuted at No. 1 on Billboard’s chart and sold nearly a million copies in the first week of release. The burden of Pearl Jam’s popularity fell hardest on singer Eddie Vedder.

“These shows are a difficult situation,” the reluctant messiah said. “I want fans to be able to see the show like it should be. But instead of making 2,000 people happy, you end up upsetting 20,000 people who can’t get in. The letters I get—‘They don’t care about their fans or they’d play bigger places.’ It’s the opposite. I’m really surprised how all this happened. You just become this huge band.”

In late November, controversy struck in the form of an abruptly cancelled gig at the University of Colorado in Boulder. Pearl Jam had been booked for a three-night stand, and the first show, on a Friday night, went on without a hitch. A crowd-control plan that had worked well in Europe was implemented. Fans in front were packed into where their surging energy could only be released upward. “Surfing”—passing people overhead—was directed toward the stage barricade, where security personnel fished out the bodies and funneled them to the outskirts.

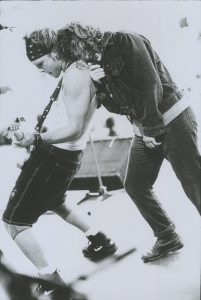

When Pearl Jam took the stage on Saturday, though, the band members were angered to see teams of headset-wearing policemen wandering through the crowd of about 4,000 people. For seemingly no reason, the campus had augmented the venue’s normal peer group security force with dozens of stern-looking uniformed officers. The disagreement focused on a university concern brought by “moshing”—in which participants in the crowd slammed into each other.

At the end of Saturday night’s show, Pearl Jam, which was “pro-mosh,” started criticizing the stage security, complaining that the fans were being treated too roughly. Vedder took the opportunity to vent his displeasure over the unnecessary police presence during the last few minutes of the show, confronting a few of the cops present and reportedly grabbing one officer’s headset.

On the morning of the Sunday show, during a meeting with campus officials and the promoter, the band insisted that the venue ease its security. When the school wouldn’t budge, alleging that Vedder’s actions the previous night had “created some tension,” Pearl Jam canceled the gig, promising to return in the spring at a different locale to honor the tickets held by disappointed fans.

The third Pearl Jam performance was rescheduled for March at the Paramount Theatre in Denver. The Paramount’s reserved seating didn’t allow moshing.

Midway through the set, after a false start on a song, Vedder alluded to the Boulder dispute. “It’s an interesting situation . . . This is a nice theater, really, and we don’t want to damage it . . . There were problems at the last show—I won’t say anything until the lawsuit’s over . . . But it seems like you’re bored, and we’ve been so excited to come here . . .”

After the frenzy, Vedder milled about backstage. “My lawyer has advised me not to talk about it,” he said. “But I won’t just pay the fine and be done with it. I didn’t do anything. I don’t want a charge of obstructing government operations on my record.”

Six months later, a judge in Boulder threw out the charge against Vedder of interfering with police.