Jethro Tull was booked to open the summer concert season at Red Rocks on June 10, 1971. In one of the most infamous events in Denver concert history, it resulted in a riot.

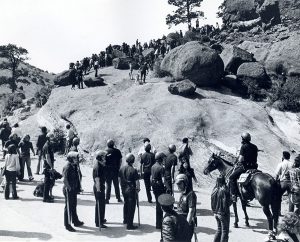

Rumors of impending unrest had surfaced in the days before the show. An estimated 2,000 fans who had not been able to get tickets went peacefully to Red Rocks to situate themselves on the surrounding rocks and hills to see and hear what they could, but there also was a militant faction determined to start trouble. Extra police were called in at 3 p.m. to control gatecrashers. At 5:30, the police, under orders from Lt. Jerry Kennedy, told the crowd they would be allowed to sit on the hill behind the theater where they could hear the music, but not see the show.

The tumult started an hour before the concert was scheduled to begin, when a number of the “hill people” started to climb over the outdoor venue’s back area in an attempt to get closer to the show; they swarmed around the perimeter, walking over the bluffs and into the top parking lot.

The police had warned the crowd that tear gas would be thrown if they didn’t disperse, feeling that the rough terrain would render any other way to maintain security impossible. The first volley was dropped from a helicopter in the upper area. Rather than acting as a deterrent, the tear gas incited the disorderly throng on to further acts of violence. The crashers picked up bottles and rocks to use as ammunition against the police.

Adding to the problem, some of the gas began to fill the canyon-like shape of the amphitheatre, wafting over the paying crowd and collecting on the stage at an alarming rate—a situation that forced Livingston Taylor, the opening act, to make a hasty exit before finishing his set. “This is supposed to be music!” he cried. “What’s going on here?”

While the police tended to the injuries outside the theater, the medical people attached to the amphitheatre had more problems than they could handle. Two doctors who went into the audience to treat severe injuries had their medical bags stolen and were rendered virtually helpless, while a small staff inside the aid station bandaged cracked skulls and revived those who had been overcome by the varieties of tear gas.

That the concert went on at all was a tribute to the perseverance of the members of Jethro Tull.

“We were leaving our hotel to go up to the show when we received word that there was a problem,” flute-playing frontman Ian Anderson said. “We set off in our rented station wagons and were met by a police roadblock that tried to turn us back. We said, ‘We’re the band,’ and we were told, ‘There’s not going to be a show, go away.’

“We thought that was ridiculous, so we managed to find a back route on a dirt road. We still had to make a fairly aggressive effort to get to the site—we wound up running a roadblock—and when we got there, we realized there was trouble going on outside. The police were trying to stop us from going to play—they felt that would make it worse. I said, ‘Look, if you don’t let us go onstage, not only are there going to be 2,000 people outside rioting, but 9,000 people inside are going to go crazy as well.’”

Reluctantly, the authorities allowed the British progressive rock band to proceed. Anderson wandered on stage with tears in his eyes. The other members were also weeping and gasping for breath—keyboardist John Evan couldn’t see his piano through the tear gas.

Undaunted, Tull played anyway. Anderson surveyed the Denver police chopper hovering in the distance dispensing periodic charges of tear gas at the rear of the assembly. “Welcome to World War III,” he croaked, and the music, much of it from Tull’s album Aqualung, went on for the next 80 minutes. Anderson was magnificent, stalking the stage and playing his flute like a man possessed, despite the circumstances.

“The gas made life very difficult in the amphitheatre itself,” he said. “The wind blew a cloud of gas over the audience to the stage. We had to stop several times. I remember seeing babies being passed down through the crowd so they wouldn’t be affected by the gas. It was a horrifiying sight. Happily, we were able to keep some sense of peaceful resolution with the audience. By playing the show, we kept the lid on what could have become a very dangerous situation.”

The show at Red Rocks was one of drummer Barriemore Barlow’s first dates with the band.

“Having slightly upset the police on the circuitous way up there, we had to be careful going down again—they saw us as the reason all this had happened,” Anderson said. “We were hiding under blankets in the back of a rental station wagon, licking our wounds, lest the rather overly anxious local police decided to encourage a fray. They shined their torches in the station wagon looking for the longhaired British rock band. It was all a bit scary. Our eyes were streaming and we were coughing. Barrie turned to me and asked, ‘Is it going to be like this every night?’”

In the wake of the riot, 28 persons, including four Denver policemen and three infants, were treated at area hospitals for injuries suffered in the disturbances, ranging from broken bones to gas inhalation. Dozens more—policemen, concertgoers and would-be gate crashers—were treated at the scene by a volunteer medical team. Twenty people, including three juveniles, were arrested on charges ranging from drunkenness to weapons violations and possession of narcotics. One parked car was overturned and burned, and several other vehicles were reported damaged.

In the aftermath, the rest of the 1971 season—Judy Collins, Burt Bacharach, Rod McKuen and the Vienna State Opera Ballet—was cancelled. The debacle convinced Denver officials to ban rock events at Red Rocks—a ruling that held until 1975.