Producer James William Guercio had gotten his start producing a string of hits for the Buckinghams circa 1967, including “Kind of a Drag,” “Don’t You Care” and “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy.” He became a staff producer for Columbia Records and began working with Blood, Sweat & Tears and Chicago.

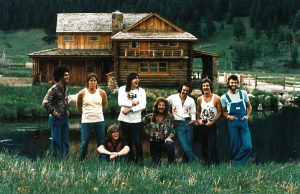

Through five albums with Chicago, Guercio gathered up enough money to own Caribou Ranch near Nederland, Colorado.

“We were still recording in New York,” keyboardist Robert Lamm said. “Guercio said, ‘I think it would be a smart idea for us to find a place where we could go and make music, and we wouldn’t have to deal with hotels and taxis and studio time, ideally in some place that would be inspiring. We could work any time we want for as long as we want.’ We looked at footage of properties; he had people looking for him. We made the move to Caribou. It was a big financial commitment on Jim’s part.”

“We must have done a third of our albums up there,” Chicago trumpeter Lee Loughnane recalled. “It was a climate where you could get away from any influence or distraction that would take away from creativity. It would result in new fits of inspiration and make for better art, supposedly. And it worked for quite a while.”

In 1973, the year Caribou Ranch opened, Chicago filmed a network television special there, Chicago: High in the Rockies. A second TV special, Meanwhile, Back at the Ranch, aired in 1974. That same year, Chicago met the Beach Boys at Denver’s Stapleton Airport.

“They had come into town to do a show. We started talking at the luggage carousel and we wound up inviting them to the studio,” Lamm said. “Peter Cetera was putting down a track for ‘Wishing You Were Here,’ and he had always envisioned having the Beach Boys’ vocals on that record. Bang, there they were at the ranch. Three of them sang on that hit.

“I looked at Carl (Wilson) and said it would be nice to do something with the two bands in concert. It was like Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland saying, ‘Let’s put on a show! My dad’s got a barn!’ The light bulbs went off over everybody’s heads. In that era, as today, everybody wanted to be a headliner. There weren’t many times when a couple of superbands would get together to do something.”

The Beach Boys had battled over their live show in the early 1970s, with Carl Wilson insisting that a constant updating was necessary, and Mike Love fighting to give the people what they seemed to desire desperately—an in-concert jukebox. The conflict became academic. In June 1974, Capitol Records released Endless Summer, a two-record set of early hits, and Spirit of America followed the next year. The collections sold in the millions.

The Beach Boys were forced to admit that their only future was in their past, and Guercio played an important role as they made that transition. He quickly moved up the ranks into a full managerial position. His company, Caribou, was officially named as the Beach Boys’ management arm, and Caribou Records the band’s label. In May 1975, under Guercio’s direction, Chicago teamed up with the Beach Boys in one of the most successful tours in rock history—a 12-city odyssey that grossed $7.5 million and played to a total of more than 700,000, despite a general recession that had hit the rest of the music business hard. Guercio did double-duty, playing bass with the Beach Boys on the tour and whipping the road band into shape.

“That tour was our comeback,” Wilson said.

The two bands appeared in a sold-out show at Fort Collins’ Hughes Stadium.

“We flew up to Colorado State University in our private plane,” Loughnane said. “I was getting ready in the dressing room, and all of a sudden I heard this ‘tea bag’ voice saying, ‘I say, chaps, how are you?’”

And there was Elton John.

“He’d been at Caribou; he’d heard about the gig,” Lamm said. “I told him to hop on stage during the encore. The show was one of those that worked from the get-go. Then Elton jumped up, played a little piano, banged a lot of tambourine, did a lot of singing and smiling. It was one of those magical moments. Everybody who was there got their money’s worth.”

It seemed almost miraculous that within a year the Beach Boys were back on top, grossing as much money without any newly recorded product as they had in their heyday. But Guercio and Caribou Management didn’t stay with them for long. The following spring, he was released from his business responsibilities with the Beach Boys. Chicago’s situation with Guercio also had been deteriorating, and the band members eventually eliminated their dealings with him in 1977.

“We had five years of incredible success. Along with that success came problems of adjusting to a crazy rock star lifestyle. I don’t know that we did a very good job of it on a personal level,” Lamm said. “Some of us were too young and not ready to look inward to see what else was in there, as the Caribou situation should have encouraged—being out there thinking about what was important and having that come through the music. A number of us weren’t ready for that—we wanted to party. We were in our mid to late 20s. We were interested in coming down to Boulder to chase girls.”

“Caribou Ranch was the beginning of the end,” Loughnane said. “Jimmy presented it to us as a band investment, and we said, ‘Okay, we’ll take a pass at it.’ But I think he had it in mind that he’d buy it and control it. We had some successful albums out of the studio. There was nothing wrong until we wanted to square up with Jim.

“Well, there was one other thing. We discovered if you stayed too long at Caribou, you got a little buggy. You’d find yourself hiding out in the woods with an elk shirt on.”