One of the most influential promoters to emerge from the nascent rock concert scene, Barry Fey moved to Denver from Illinois in early 1967. After a trip to San Francisco’s Haight Ashbury district, he contacted Chet Helms, manager of Janis Joplin’s band, Big Brother & the Holding Company, to discuss bringing a bit of the “Summer of Love” scene to Denver. Joe Neddo of the band Boenzee Cryque informed Fey of a recently closed nightspot in Denver, a rectangular stucco building in an industrial stretch of Evans Avenue.

It became the Family Dog, named after the San Francisco collective that sponsored dances at the Fillmore and the Avalon Ballroom.

Fey became the local booking agent for the 2,500-seat concert hall, which opened on September 8, 1967, with a show featuring Joplin and Big Brother plus the heavy sounds of Blue Cheer. For ten glorious months, the Family Dog prospered, hosting an amazing roster of talent—the Grateful Dead, the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, Van Morrison, Jefferson Airplane, Frank Zappa, Cream and more.

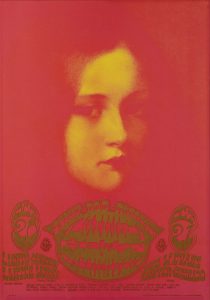

Psychedelic images were hand-painted on the floor. Colorful posters and handbills prepared by San Francisco artists such as Rick Griffin, Stanley Mouse and Alton Kelley promoted the shows. The most expensive ticket ever at the venue, for the Doors on New Year’s Eve 1967, cost $4.50.

But the club struggled to stay open, both financially and with mounting police pressure. The Denver police hated the idea of having a hippie club in their city and had done all they could to stop the Family Dog from opening. Helms and his people endured a barrage of harassment and illegal searches.

It was Canned Heat’s bad luck to show up on a Saturday night, October 21, 1967, just as the police figured they’d bust one of the bands and the bad press and legal troubles would carry over to Helms. Officers followed the members of Canned Heat, a seminal influence on white urban blues, to a nearby motel at Santa Fe and Florida.

“The band didn’t have any dope in Denver—everyone knew that things were tough there—so the guys showed up clean to play that gig,” said drummer Fito De La Parra, who joined Canned Heat a few months later. “But the police dispatched a stool pigeon with some weed to the hotel to socialize and turn us on.”

It turned out the stool pigeon was an old friend of Bob “The Bear” Hite, the band’s singer.

According to De La Parra, “Bear was raised in Denver before his family moved to Los Angeles, so he had made some friends there when he was a kid. So he trusted the guy, until he suddenly disappeared out the door and the cops came barging in to ‘discover’ a package of weed under the cushion of the chair where the ‘friend’ had been sitting. They busted everybody on charges of marijuana possession—still a big offense in those days. A judge wasn’t available until Monday, so the band spent the weekend in the can.

“It was a terrible thing. To pay the fines and court costs, the band had to sell its publishing.”

The drama was immortalized in “My Crime,” from the album Boogie with Canned Heat:

I went to Denver late last fall

I went to do my job, I didn’t break any law

We worked in a hippie place

Like many in our land

They couldn’t bust the place, and so they got the band

’Cause the police in Denver

No they don’t want long hairs hanging around

And that’s the reason why

They want to tear Canned Heat’s reputation down

At the time of the Family Dog bust, Hite said to a reporter, “To sing the blues, you have to be an outlaw. Blacks are born outlaws, but we white people have to work for that distinction.”

The Family Dog began to falter when the club obtained an injunction forbidding police presence on its premises. Rather than benefitting the venue, news of the injunction resulted in diminishing patronage. After a short stint as the Dog, the club closed in July 1968. It enjoyed a much longer and successful run as a gentlemen’s club.