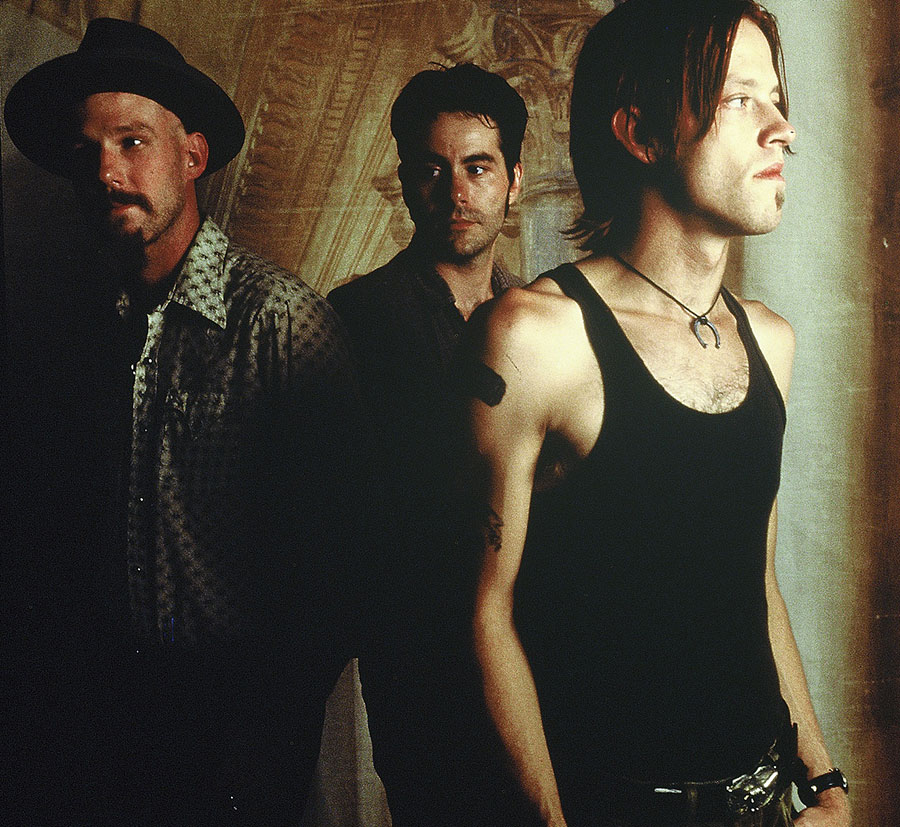

Sixteen Horsepower

When Sixteen Horsepower formed in Denver circa 1992, fans labeled the gripping, atmospheric music “prairie-goth,” “roots-gloom” and “spooky campfire.” Whatever the band was doing, it wasn’t a take on post-grunge alternative music. The haunting, lingering sound was a mix of rustic blues wailings, old-time country tunes and modern-rock dramaticism.

The vibe reflected David Eugene Edwards’ love of traditional music. The Colorado native grew up in Englewood and Littleton and attended Arapahoe High School.

“I played electric guitar in punk rock bands in high school, but I’ve always played the acoustic guitar,” Edwards said. “I started getting into other types of music—not necessarily quiet, folky music, just ‘rootsy’ music from all over, Russia, Hungary, Czechoslovakia. That’s my family’s heritage.”

For a good portion of his youth, Edwards was raised by his grandparents. His earliest memories are of traveling from town to town in Colorado listening to fire-and-brimstone sermons by his grandfather, a Nazarene preacher.

“It’s a real old, Southern-style sect,” Edwards said. “I always like the music around church. That’s my main influence.”

Married at 17, Edwards left his grandfather’s church (with the old preacher promising eternal damnation) to seek a more individualistic Christian path. He became the foundation of Sixteen Horsepower. Other members included bassist Keven Soll and drummer Jean-Yves Tola, then Pascal Humbert on bass and Jeffrey Paul Norlander (a co-founder of Edwards’ original band, the Denver Gentlemen) on strings and guitar.

“I sing about the things that are important to me, plain and simple,” Edwards said. “Things that are lasting and worthwhile don’t change. There are a million bands out there to listen to, but there’s a certain amount of responsibility that comes along with making music. I refuse to take the attitude of ‘I’m an artist, so I can do what I want.’ Your work affects people, and you have to be conscious of it.

“There are different aspects of what we do. Some people latch on to the Americana thing. Some people latch on to the European traditional music part. Some people latch on to the spiritual aspect. It’s difficult to please all of them all the time.”

Edwards’ mournful voice and the edgy emotional content of his lyrics were driven by vintage acoustic instruments—bandoneón (a turn-of-the-century button accordion), violin, cello, hurdy-gurdy and banjo.

“At the beginning it was a matter of money—I couldn’t afford anything new or of any certain quality, so I would go to pawnshops and used-music stores,” Edwards said. “The guitars that I played weren’t very popular—they were considered cheap and no one really wanted them, so I basically got them for nothing.

“A friend of mine knew I love hillbilly music, so he found a banjo in the trash and gave it to me, and I started playing it. I saw the used bandoneón in the window of a Boulder music store and got it for $130—it was a $2,000 instrument, 150 years old, but they had no clue what it was. They just wanted to get rid of it. I played it for years to the point where it fell apart.

“I just love older instruments. They have a different character and quality that you can’t get out of newer ones. I try to get as old as I can possibly use to be roadworthy and function every night.”

Sixteen Horsepower’s attitude was determinedly antique, and Edwards unleashed his doubts about sin and redemption with a religious fervor that echoed kindred spirits Nick Cave and the Gun Club. Two fine major-label albums, 1995’s Sackcloth ‘n’ Ashes and 1998’s Low Estate built up the band’s following in Europe. In the annual best-of list in OOR, the Dutch equivalent of Rolling Stone magazine, as voted for by Dutch critics, Sackcloth ‘n’ Ashes reached No. 4. Low Estate reached No. 9 in the OOR list.

The irony? Internationally, the Denver-based band’s rugged American music was embraced and understood on a more mainstream level than on his home turf.

“We went to Europe constantly since ’95, and each time the interest expanded to new countries and cities, and the crowds were bigger,” Edwards said. “And then to come back here and people in Colorado don’t really care, or don’t believe it in a way—it’s odd.

“On an overall level, traditional music is so much more accessible and everyone is more interested in Europe. Even teenagers aren’t as distant from their folk music as Americans are. They’re a little more conscious of keeping their own creativity, discovering something new for themselves instead of being told what to listen to.

“To me, it seems like they listen to this music because they’re not associated with it in the way that we are. The reasons most Americans don’t take it to heart like they do other types of music is because it makes them think of an earlier time that is depressing to them, of slaughtering Indians and slavery—a time of cruelty. America is trying to go into the future as fast as possible to escape that. But you can’t.”

Sixteen Horsepower released two more studio albums and toured extensively, taking a break in late 2001, as the group Wovenhand became the dominant outlet for Edwards’ music and lyrics. Sixteen Horsepower finally called it quits in April 2005 after years of sitting on the fence, citing “mostly political and spiritual” differences. Edwards remained active in Wovenhand.