Eddie Van Halen—whose repertoire of ripping riffs, runs and solos made him an influential guitar deity and the musical brains behind his band, Van Halen, America’s most important hard rock act of a generation—died after a long battle with lung cancer on October 6, 2020 at the age of 65.

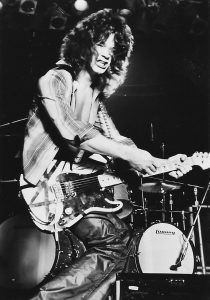

Eddie was 23 years old when Van Halen opened for Black Sabbath at Denver’s McNichols Arena in November of 1978, and “Eruption,” his showstopping solo piece from the band’s self-titled debut album, had alerted the world to his complex harmonics, innovative fingerings and two-handed tapping on the guitar neck. Van Halen had toured that year with such acts as Aerosmith, Ted Nugent, Boston and Foreigner—all of which came away singing the praises of Eddie’s pioneering and explosive guitar work.

Swaggering lead singer David Lee Roth, he of the ribald wit and flair for unabashed showmanship, willingly assumed the task of propagandizing in interviews, but Eddie told the story of building a nucleus of fans in California during their early days. The four guys got together in high school in Pasadena and played Cream-like jams at backyard parties, charging a buck a head—and soon they were drawing 800 people. So when they started looking older, they moved the parties indoors, renting halls and promoting themselves with self-made flyers. They soon were drawing 3,000 people and had proven themselves far beyond the California state line.

By 1979, Van Halen had expanded its live repertoire for two concerts at Balch Fieldhouse in Boulder, reinforced by Eddie’s flashy guitar pyrotechnics. Backstage, over the din of a Donna Summer tape, he had no doubts that the last bastion of acceptance for the group, AM radio airplay, would crumble with the release of “Dance the Night Away,” a terrific power-pop single off Van Halen II that was a tasty change-of-pace from the group’s sonic blitzkrieg style.

Van Halen invaded McNichols Arena as headliners in 1980. Eddie boasted that the stage show featured 850,000 watts of lighting—“Sure, but all my hair is falling out!” he quipped.

“I come up with the seeds of the music during our one week off every eight weeks,” he explained of the songwriting process. “I just slap the ideas on tape and we take ‘em back out with us and make songs! We all arrange, and Dave has the most lyrical input—and it’s not too hard to figure out what he’s thinking about. We just go in, mike the stuff, and that’s the way it comes out. I use older amps than I use live, which give you a little more razor-edged trebly sound, but all I do is put a couple of microphones up to a cabinet—that’s as much as I can see, anyway. It’s pretty cut and dried, simple—and that might be the difference. Most people go in there and use a lot of fuzz/wah/phase garbage and this and that, and instead of being clean and direct, it’s covered up by a bunch of crap.”

Ted Templeman, the band’s producer, had mentioned Eddie in the same breath with jazz-guitar legend Django Reinhardt in a Rolling Stone magazine article. “I don’t really know how I feel about that,” Eddie demurred. “I mean, there’s so many so-called guitar heroes around that really don’t play that good, and the kids go crazy about them. And the ones that play good, a lot of times they’re not recognized. Sometimes if I really play bad, the kids still love it—and times when I think I really played well, with some good improv stuff, the kids can’t tell! I hear a lot of guitarists who are really excellent, who just because they don’t have a flashy guitar or the haircut, the kids…well, maybe that isn’t the right thing to say to our audience. It’s a bit frustrating—you kinda wonder, why should I continue getting better? The better you get, the less they understand.”

Eddie considered Allan Holdsworth, an Englishman of some renown given to progressive music, an underrated guitarist. “Why do these guys, when they do get so good, start playing space music? Why don’t they apply that knowledge to 4/4 time and singalong-type of music? We don’t plan it out, but musicians naturally change—I don’t like to call it maturing,” he laughed. “I personally get tired of doing the same old thing. We just do what we feel like doing. I think we all have the simple thing in us. Look at Christmas carols—they’ve got to be the most popular tunes on earth, and they’re all 4/4 singalongs. There’s no heavy plan to our albums—we just write a bunch of songs the week before it’s supposed to be released and say, ‘Whaddya wanna put on it?’ It’s true, we don’t plan what we do. It’s all spontaneous. It’s a lot harder to put together a 4/4 song—anyone can get complicated and do something that no one understands! Then they stand up there like a ‘true artist’ which to me is a bunch of bull. It’s harder to be simple—when was the last time you heard a new Christmas carol?”

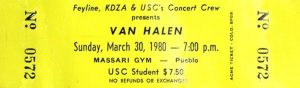

Earlier on the ’80 tour, the band played at the University of Southern Colorado in Pueblo, where reports claimed that they caused more than $10,000 worth of damage, resulting in concerts to be banned from the campus site.

“It was actually a bunch of bull. There is a clause in our contract, a backstage rider with the promoters, that says no brown M&Ms in our M&Ms—which is a joke (to make sure the rider was being read), okay? And there was a bowl of M&Ms back there with some brown ones, so we started taking them out and throwing them around. So we stomped a couple into the carpet, which isn’t so unusual—we have food fights backstage all the time, which really doesn’t cost that much. It’s not destroying any fixtures, lamps or doors. They said we destroyed a bunch of bathrooms, but those weren’t backstage, they were out front where the public was. And I’ll be damned if I’m gonna walk out in an audience of 10,000 and kick 10 urinals off the wall—I don’t think we’d be in a position to go to the bathroom if we made it through the crowd! Still, we were blamed! We have fun like everyone else, nothing a little wallpaper and paint won’t take care of. But not no $10,000 worth of damage to urinals and bathrooms! We didn’t even hear about it until we read about it in Rolling Stone.”

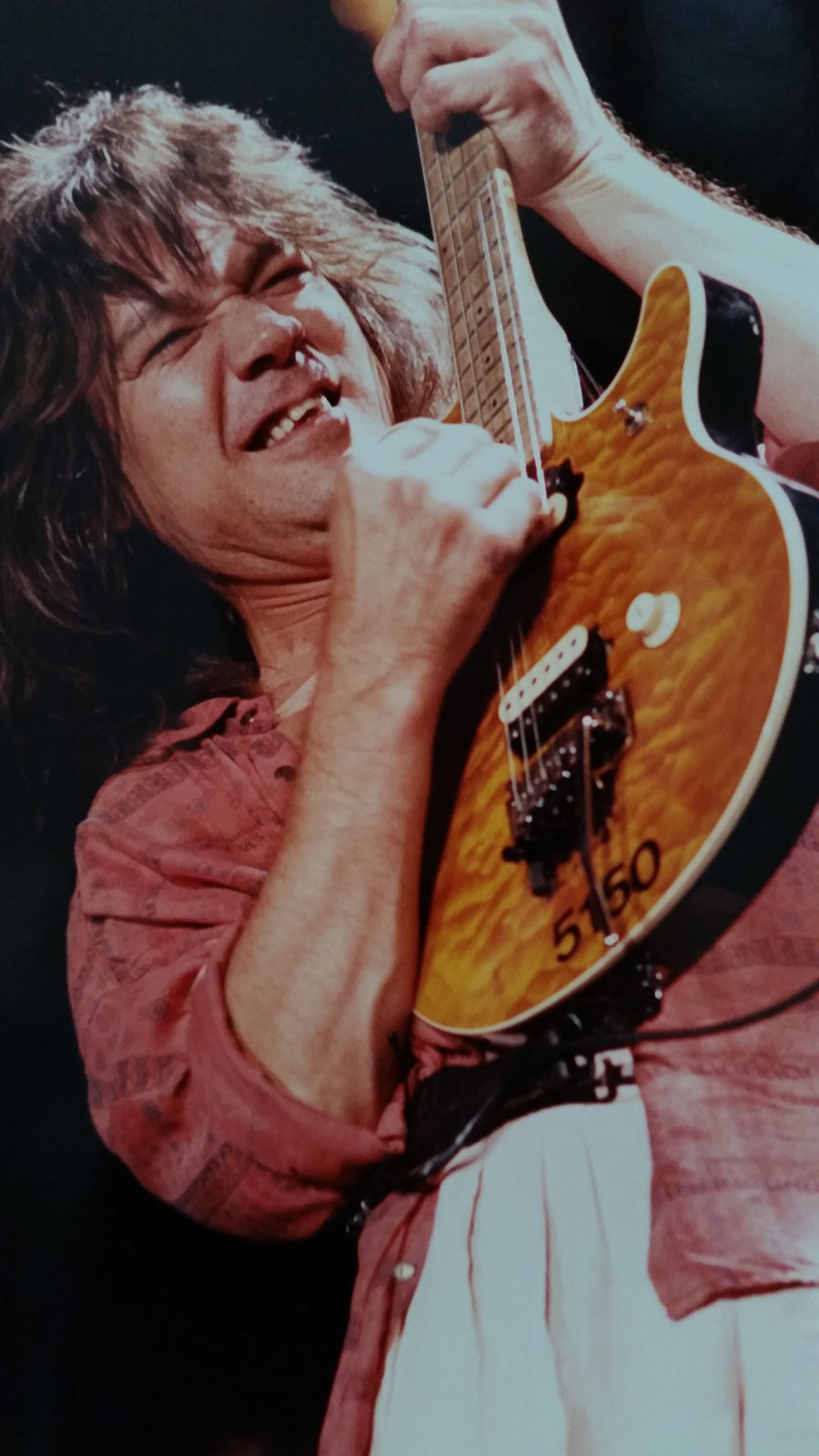

In 1985, when Roth announced his departure from Van Halen, it seemingly signaled the end of the band’s six-album reign as America’s top hard-rock attraction. The immediate result had been a wealth of bad-mouthing between Roth and his ex-bandmates in the rock press. But by naming Sammy Hagar as Roth’s replacement, Van Halen evolved into a revitalized unit—the group’s 5150 album, also the name of Eddie’s home studio and the Los Angeles Police Department code for the criminally insane, became Van Halen’s first No. 1 album in its history. Eddie continued to combine his electrifying technique with potent ideas, and Hagar’s enthusiasm both moved and inspired him.

“On the record, he really made a difference,” Eddie noted before Van Halen’s 1986 performance at Boulder’s Folsom Field. “It’s like Arnold Schwarzenegger’s book Stay Hungry—it’s no longer ‘You feel like working? Nah, let’s wait until tomorrow. Or let’s wait until next year!’ With Sammy, his energy is just contagious. He’s a great guy, a great worker. Absolutely nothing like…” And he dissolved into laughter.

The hit single “Dreams” featured a grand piano intro played by Eddie, and “Love Walks In,” a pretty but powerful ballad, had attracted a whole new pop audience for Van Halen.

“My only problem with that is the terminology,” Eddie commented. “To me, music is music, and if it’s good, it’s pop. I think it’s funny that Led Zeppelin was considered the ultimate heavy-metal band of all time, and half of their music was acoustic. Whenever you reach a certain point of success, some people are going to find fault—‘Oh, you’ve sold yourself, you’ve gone mainstream.’ Well, mainstream only means that you’re successful at what you do.”

The group celebrated its first 15 years at Fiddler’s Green Amphitheater in 1993. Eddie’s guitar stunts were mesmerizing as usual, and Hagar jumped all over the stage like the arrested adolescent he was. Prior to the concert, Eddie regaled friends backstage with a tale. At Boston’s Four Seasons hotel, he was awakened from a sound sleep.

“I felt something in my head bothering me,” he recalled. “I went in the bathroom and put some cleaning solution in my ear—and this live beetle comes crawling out. I put it in a box and showed it to the hotel management—you know, what the hell is going on?” The hotel kept the scarab and named it Eddie.

On September 21, 1995, a couple of inches of snow fell at Fiddler’s Green, and the concert at the outdoor venue was cold, wet fun. The musical focus was on Eddie—sporting facial hair and a wool cap pulled over his trendy new crew cut, he whipped off his incendiary blend of virtuoso moves and sheer Richter-ready propulsion. And he even jumped around a little, although his hip hurt when he stood to play. At the beginning of the tour, he had been diagnosed with avascular necrosis, the same condition that ended the career of two-sport star Bo Jackson. Doctors told him hip-replacement surgery could wait until after the tour.

“He went through a real bad period—he was limping and walking with a cane for a while,” Hagar said. “He had stopped drinking and settled into a mellower groove, and it was tough after years of alcohol abuse—all of a sudden he started feeling aches and pains in his body. But he’s almost completely healed himself by taking it easy, and it’s been nothing but positive for his playing—anyone’s a better guitarist with both feet on the ground than three feet in the air. I don’t know if it’s the sobriety or the hip, but I think it put him in a good position where he really had to concentrate.”

Van Halen continued to battle LSD—lead singer disease, “when the whole planet revolves around them,” according to Eddie. In 1996, the band said goodbye first to Hagar, then (again) to Roth. Van Halen invited Gary Cherone, whose group Extreme had disbanded, but he only hung around long enough to record 1998’s Van Halen III. Hagar and Roth, the rival former frontmen, joined forces for a series of shows in 2002, including one at Fiddler’s Green. Eddie had previously disclosed that he was battling cancer. The notoriously private guitarist was reportedly healthy after receiving treatment.

Roth rejoined the Van Halen fold for a 2015 tour, the band’s last, and they played Red Rocks Amphitheatre for the first time. “My voice and the sound of Eddie Van Heineken’s guitar is as well-known as the McDonald’s arches or the Nike swoosh,” Roth had said. For once, no brag, just fact. Godspeed to one of the seminal players in rock history.

Van Halen with KAZY-FM staff and contest winners, backstage at the “Monsters of Rock” concert at Mile High Stadium, 1988 (Eddie Van Halen, far right; G. Brown, third from right)